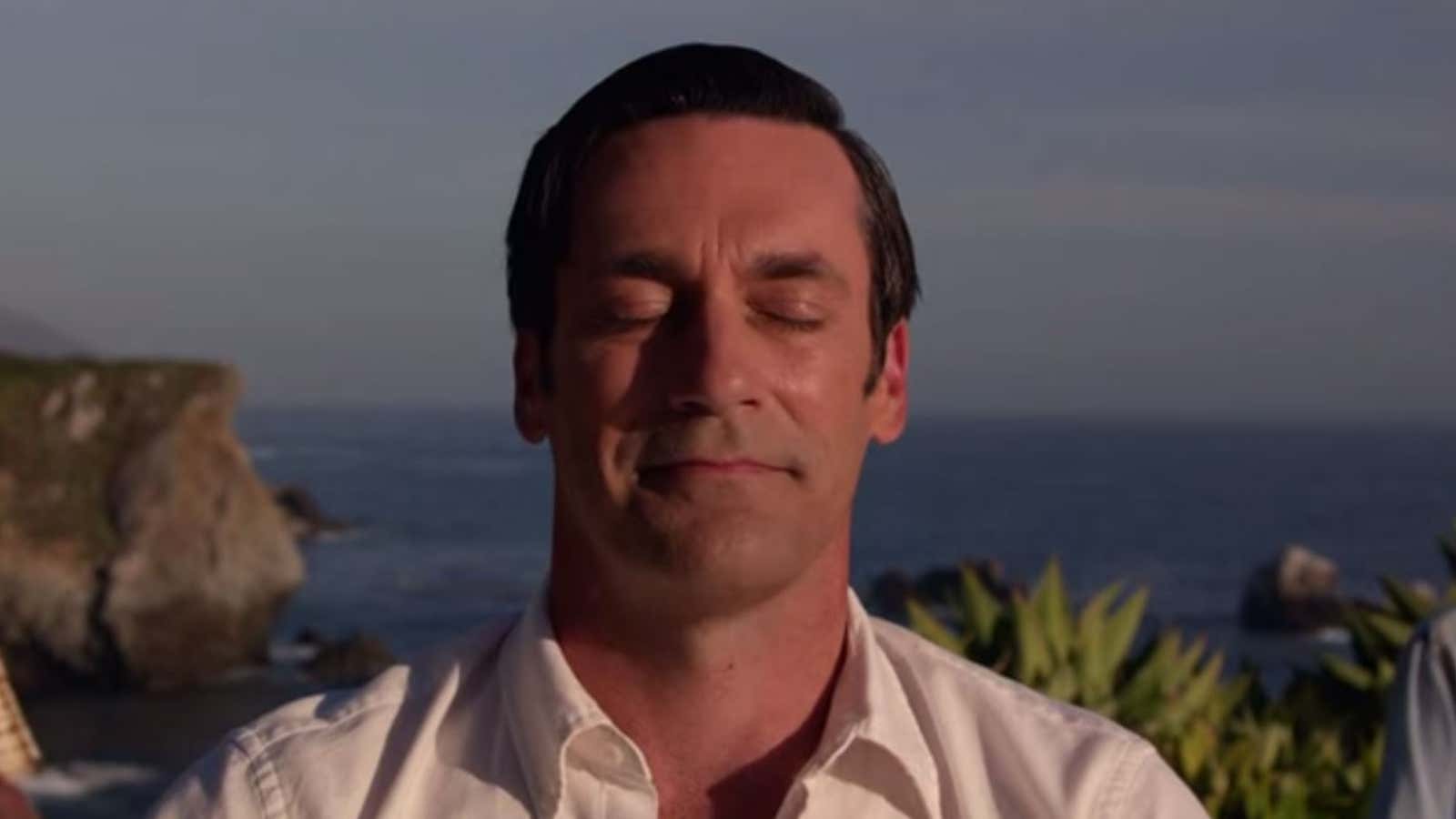

Don Draper’s smile was always slow moving and surprising when it happened. There was no doubled-over-tears-streaming-down-his-face-laughter in his life. No belly laughs or card games or trash talking over sports. There was, however, lots of restraint, reticence, brooding and cool wit. And so, in the last scene we see him in, he has a wry smile in a yoga pose at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, where serious introspection is expected. It’s easy to project that Don’s smile is Mad Men’s creator Matthew Weiner’s smile, laughing at his audience that a show that has been thoughtful, intuitive, cynical and subtle for the past seven years would go out in such a saccharine, predictable way. But I am apt to give Weiner the benefit of the doubt that this was by design, because, well, Sopranos.

Throughout the course of the seven seasons, Mad Men seemed to be about unraveling the myth that attaining the American Dream engenders happiness. The show was about creating lies to keep people buying; filling emotional voids with shiny new things. It was about a main character that was alternately narcissistic and without judgment. None of the characters or storylines was predictable or came packaged in a neat little box.

“I’m not the man you think I am,” Don Draper spoke desperately into the pay phone to Peggy in the final episode.

“No one cares that I’m gone,” Leonard says in the final episode to the encounter group at the retreat, talking about his family, before Don Draper crosses the room to hug him, in shared understanding of the shortcomings of having everything, but really having nothing at all.

“He has no people!” Gene, Betty Draper’s father, yells to her about Don in season 2, episode 10. “You can’t trust a person like that.”

“You’re not my family,” Stephanie, Anna Draper’s niece says, instantly creating distance between her and Don in the final episode.

“They taught us at Barnard about that word, ‘utopia’…..‘ou-topos’ the place that cannot be,” Rachel Menken tells Don in Season 1, episode 6.

“Love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons,” Don said in a pitch meeting in the pilot episode.

“Advertising is not a comfortable place for everyone,” Shirley tells her boss, Roger, in the penultimate episode, before she lightens the mood by telling him she was amused by him, with a tone that suggests she was laughing at him, not with him.

At its core, the show was about how people that benefit from white privilege and racism suffer in ways that they’re unwilling to reconcile because of the short term benefits of privilege. The show was about America not reconciling honestly with its own sordid past and present. It was about being unwilling to change and about people losing their humanity as a result. Like Robert Downey Sr.’s film, Putney Swope, released in 1969, a comedy satirizing the advertising world where Putney, the only black person at the firm accidentally gets voted to lead the firm and fires all the white people, Mad Men is about the fear of change.

In the episode which featured Dr. Martin Luther King’s death, the overwhelming sentiment is that it is a tragedy of inconvenience— commutes will be delayed and there will be potential property damage. Even the slightest changes can set people in this world off balance and adrift. Even Don, who is physically always on the run from something and looking for something new, resorts to his same habits and makes the same mistakes.

In real life change did happen in corporate America. But it didn’t happen in the boardrooms of Madison Ave. because of any company’s moral conscience. Legislation was enacted. There was the ACLU and the EEOC, as Joan mentions in the final episode. Corporate America changed because of the bottom line and because they had no other choice.

In the 1950s the black consumer market had risen, with estimates topping $19 billion per year, according to Jason Chamber’s book, “Madison Avenue and the Color Line: African Americans in the Advertising Industry.” A selective patronage campaign started in 1961 by 400 ministers motivated area companies to employ blacks, not as tokens, but in white collar positions in Philadelphia. Similar campaigns happened in Baltimore, Detroit and New York City. The National Urban League, Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) united in working towards integration in advertising. CORE members met with agencies and advertisers, including Coca Cola, about integrated advertising and increasing black employment and were successful in their efforts. In November 1963, the NAACP addressed a body of advertising representatives. Change happened swiftly with the threat of boycotts.

It was Roquel Billy Davis, a black former music executive courted by McCann-Erickson, who produced the song for the Coca Cola commercial, “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” that ended the series. Davis came to the company in 1968, a month before Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination. He would eventually be credited for popularizing song form in advertising and eventually became the vice president at McCann-Erickson and has a conference room named after him. He also worked on Miller Life, another campaign featured in the series, producing the song “If You’ve Got the Time.” There were other black executives. George Olden, the art director at McCann-Erickson, designed the Clio award that Don wins. Roy Eaton became the first black person at a major agency with a creative function on general accounts in 1955. In 1968, he would rise to become the Vice President at Benton & Bowles, an agency with a diverse employee pool. None of these black executives are reflected in the narrative of Mad Men nor are any of the black characters on the series allowed any complex, interior lives.

Audiences who were reveling in Leave it to Beaver nostalgia were satisfied with the finale. Peggy wouldn’t be a career-obsessed spinster. Joan would lead the way for the Martha Stewarts of the world. Pete and Trudy got the American Dream. Don created perhaps the most famous advertising campaign in history or he spent his life as a hippie in California with a nice cushion in case he changes his mind. Everyone is filthy rich. The genius of Mad Men is that it’s as much about what’s invisible and what’s not said as what is. Did things really improve for each character? Or was it like the rest of the series, where the best predictor of current behavior is past behavior?

Will they all just end up spinning circles on Don’s imaginary carousel, not really having changed at all and just enjoying, as Don’s girlfriend Faye told him “the beginnings of things?”