Spotify can’t make money on music, so it’s expanding beyond it

“We’re only at the beginning of something really exciting,” Spotify CEO Daniel Ek says. “There is a profound change happening in music.”

“We’re only at the beginning of something really exciting,” Spotify CEO Daniel Ek says. “There is a profound change happening in music.”

While the first of these observations is perhaps subjective, there’s certainly no doubting the second. Streaming services are rapidly overtaking digital downloads and CD sales to become the most lucrative format in the music industry. It’s a sea change, and as the biggest player in on-demand streaming, Ek’s company would seem well-positioned to benefit from it.

So why did Spotify feel the need to announce an overhaul of its service this week at a press event in New York?

In a word: Apple.

At its annual developer conference beginning on June 8, Apple is expected to relaunch Beats, the streaming music service it bought for $3 billion from rapper Dr. Dre and others last year. And that could bring about some profound changes of its own.

What a bona fide Apple streaming music product will look (or sound) like remains to be seen, and there’s no guarantee it will be any good. But the Tim Cook-led company has a powerful weapon in its arsenal (in addition to its mountains of cash): it already has 800 million credit cards on file for iTunes music customers. If it can convince just a fraction of these users to become streaming subscribers, it could reshape the streaming music landscape completely.

And so Spotify is moving quickly in an attempt to insulate itself (more on that in a minute) while it wrestles with two other big problems. One is playing out very publicly, and that’s the criticism the Swedish-based company has faced in the past year from high-profile artists like Taylor Swift and Jay-Z, who now has his own streaming service, Tidal. The other, more troublesome problem for Spotify is that so far, despite building an industry-leading base of 15 million subscribers and 60 million total users, its core business of streaming music just hasn’t been a very lucrative activity.

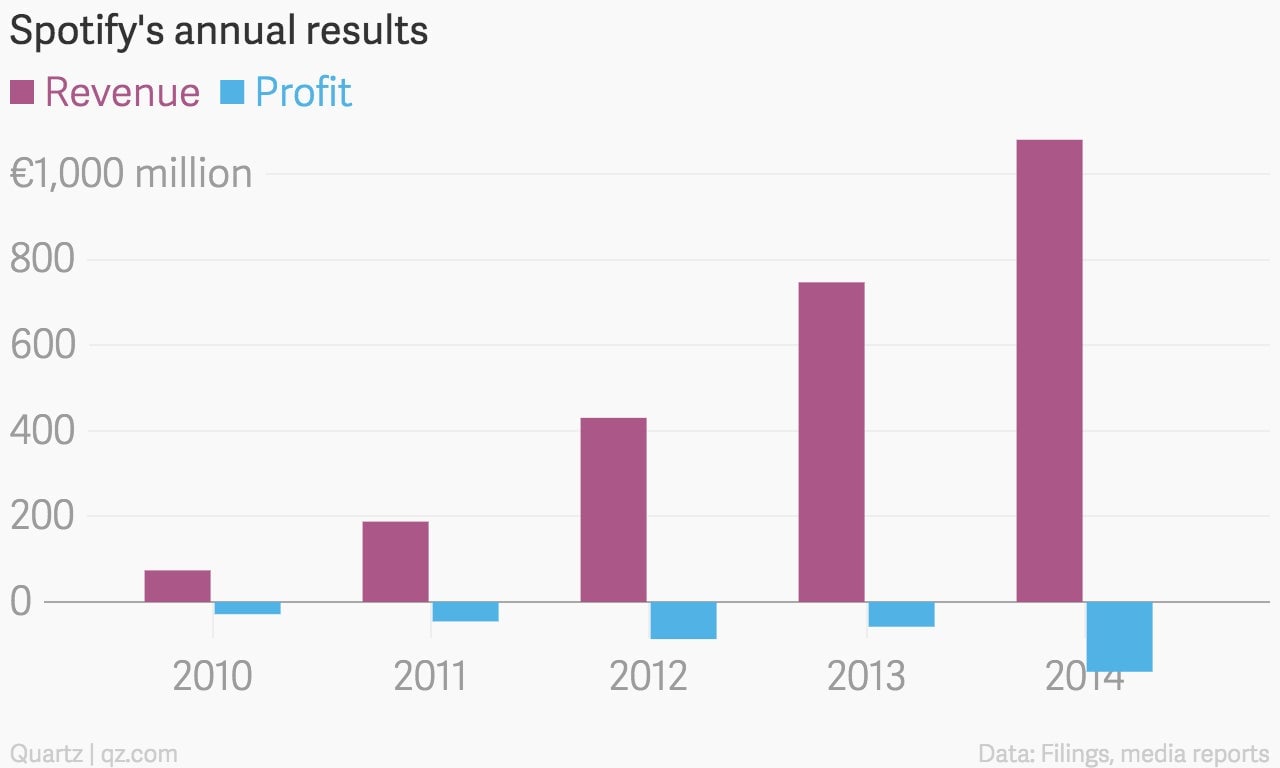

Sure, Spotify is still in pre-IPO expansion mode, and like many others in that camp, it’s losing money. Yet financial documents recently obtained by the New York Times (paywall) and others show that the company’s financial losses are actually deepening at a faster pace than its revenue is growing.

Previously unseen details of of a contract between Spotify and Sony, one of the three major record labels, obtained by The Verge this week, go a long way toward explaining why.

The contract, which was signed in 2011 and was due to run for up to three years, shed unprecedented light on the onerous royalty costs Spotify has faced. It confirms that the company had to fork over large advances to Sony just to access its song library, and pay steep royalties when its songs are streamed. Those royalties were fixed at a high proportion (60%) of Spotify’s gross revenue. Music industry sources say the other major labels, Universal and Warner, would have similar deals in place.

What all of this means is that Spotify’s core music business has a scaling problem. Presuming the company’s current contract with Sony has similar terms, then Spotify’s content costs, including royalties to publishers, are stuck at about 70% of its revenue, regardless of how big the user base grows. This means there is not that much left over to pay for the other costs of running the company, including infrastructure, employees, and promotional activities.

That’s a structural flaw when you’re competing with deep-pocketed rivals, which is why the Apple threat puts Spotify’s challenges into such sharp relief.

The only way to lighten the royalty burden is to become big enough to bully the labels into reducing the royalty rate, something that seems unlikely in the short term. These same labels have been pressuring Spotify to drop or amend its free, ad-supported service, which they argue is dissuading people from subscribing, but which Spotify relies on as a key driver of paid subscriber growth.

Of course, professional investors don’t seem to be particularly concerned about this dynamic. Several of them, including private clients of Goldman Sachs, just agreed to infuse another $350 million into the company, valuing it at more than $8 billion.

But the capital influx can’t mask the fact that streaming music is a tough business. This is fine if you are Apple or Google and using music as a loss-leader to sell devices or to keep people engaged with your search-advertising ecosystem. It’s a bigger problem if music is your core business. So it should come as no huge surprise that Spotify is branching out beyond it—which brings us back to the Spotify overhaul that Ek and his colleagues announced in New York this week.

It includes the very logical addition of podcasts, and a partnership with Nike to offer a tool that will generate playlists while you are running, based on your listening history and running tempo. Most important, though, are the deals that Spotify has struck with just about the entire mainstream media world, including Disney (and its sport subsidiary ESPN), Viacom, CBS, NBC and many others, to offer short-form video clips, designed for consumption on your daily commute. “We believe it will keep Spotify users happy and engaged during the day,” Ek says of the video offering. “Plus, it’s really awesome content.”

What Ek didn’t say is that it is also almost certainly cheaper content than music from the major record labels. It’s a way for Spotify to get people to use its service without having to give the content providers a 70% cut of the revenue.

Effectively, Spotify wants to become a 24-hour entertainment destination, the central hub for all the entertainment content its users would consume on a mobile device. That’s not an ambition shared by many competitors—not yet, at least. “I think there is still lot of education about the current value proposition [of a streaming music service], which is music, before we even think about video,” says Ethan Rudin, the CFO of the streaming music service Rhapsody.

Ek, for his part, insists that Spotify is still first and foremost about the music. “We are a technology company by design, but we are really a music company at heart,” he says.

But it’s pretty clear—even to Spotify—that it can no longer afford to act that way.