It’s always darkest before the dawn.

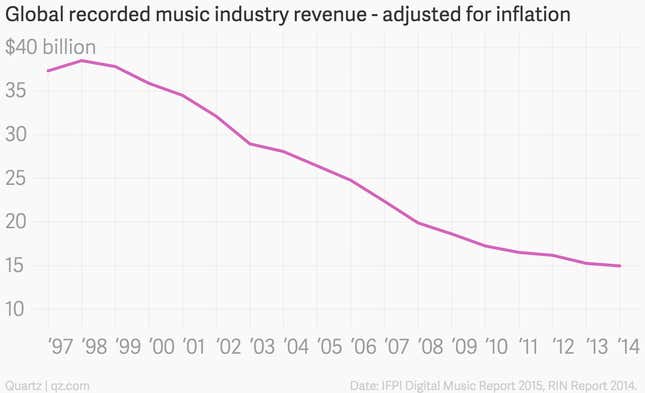

At least that’s what executives in the recorded music business will be telling themselves this morning after new figures released by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry showed that global revenue hit another low last year, falling below the $15 billion threshold in 2014 for the first time in recent memory.

Once adjusted for inflation, the global recorded music industry has basically been cut in half in less than two decades. That can largely be explained by growth in piracy and illicit file-sharing services, and the busting of the industry’s product bundle (generally known as the album) with the advent of individual track downloads through services such as iTunes.

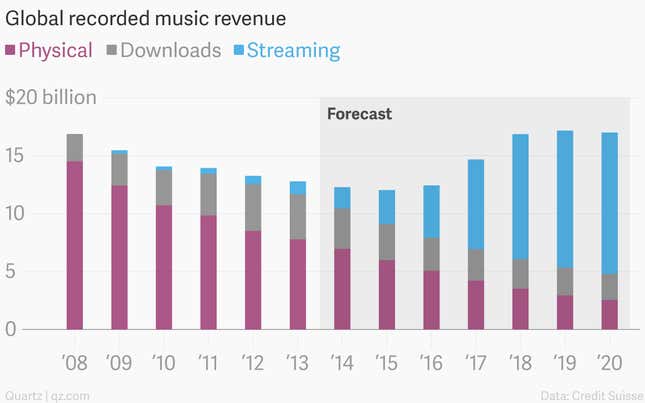

The music industry is now going through another transformation in the form of all-you-can-eat subscription streaming music services. And the good news is, at least according to some bullish projections out there, growth in streaming could be what leads the industry out of the quagmire it finds itself in today. Forecasts released by investment bank Credit Suisse last year suggest that if streaming does go mainstream, the industry could return to revenue growth as soon as next year.

At the moment, streaming remains a niche activity. Spotify, the biggest on-demand service, has 15 million paying subscribers and 60 million active users, which is not that much in the scheme of things. This could change though. Spotify is cashed up and looking to expand. Apple is poised to unveil its streaming service in coming months, and YouTube is preparing a subscription audio product of its own.

Last month, a group of investors campaigning for changes at Vivendi, the French media conglomerate which owns the world’s biggest record label, Universal, forecast that by 2020, 5% of all smartphone users, or more than 250 million people, will be paying for a streaming music subscription. Streaming subscriptions cost roughly $120 a year, which is more than the average consumer spent on music even back in the industry’s heyday. So there is a scenario on the horizon where a reasonable portion of consumers will be spending more money on music than ever before.

There’s a long way to go before we get there though. High-profile musicians and record labels remain skeptical about streaming, which is changing the way they get paid (instead of large upfront payments from album sales, the royalties more closely resemble annuity streams). “It’s a longer tail,” Glassnote Records founder Daniel Glass told me at the South by Southwest conference last month. “It’s very hard for some executives to understand that.”

Also, Martin Goldschmidt, the founder of the UK-based indie label Cooking Vinyl, points out that the profit margins on digital music are much fatter than on physical music, because the costs of distributing it are much lower. ”An old finance director once said that revenue is vanity and profit is sanity,” he explained in an email, “so the focus on revenue risks missing the point.”