On the morning of July 9, 2011, we were climbing a remote hill near the western shore of Lake Turkana in northern Kenya.

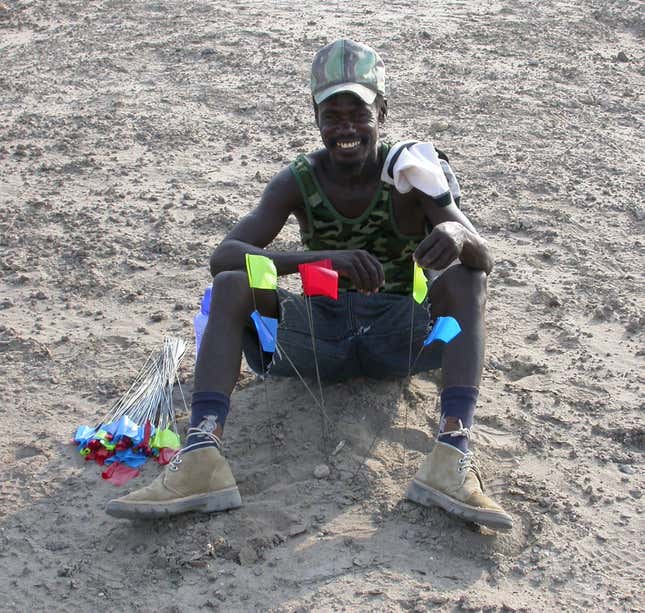

Our field team had accidentally followed the wrong dry riverbed, the only way of navigating these remote desert badlands, and we were scanning the landscape for a way back to the main channel. Something felt special about this particular place, so before moving on, we all fanned out and surveyed the patch of craggy outcrops. By teatime, local Turkana team member Sammy Lokorodi had helped us spot what we had come searching for.

We, and the West Turkana Archaeological Project which we co-lead, had discovered the earliest stone artifacts yet found, dating to 3.3 million years ago. The discovery of the site, named Lomekwi 3, instantly pushed back the beginning of the archaeological record by 700,000 years. That’s over a quarter of humanity’s previously known material cultural history. These tools were made as much as a million years before the earliest known fossils attributed to our own genus, Homo.

Stretching the record further back

In the 1930s, famed paleoanthropologists Louis and Mary Leakey unearthed early stone artifacts at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. They named them the Oldowan tool culture. Later, in the 1960s, they found hominin fossils in association with those Oldowan tools that looked more like later humans than the Australopithecines discovered there previously. The Leakeys assigned them to a new species: Homo habilis, or handy man.

Since then, conventional wisdom in human evolutionary studies has supposed that the origins of knapping stone tools by our ancestors—that is, chipping away flakes from a stone to make a tool—were linked to the emergence of the genus Homo. The premise was that our lineage alone took the cognitive leap of hitting stones together to strike off sharp flakes, and that this was the foundation of our evolutionary success. Scientists thought this technological development was tied to climate change and the spread of savanna grasslands; our ancestors innovated with new tools to help them survive in an evolving landscape.

Over the last few decades, however, subsequent discoveries pushed back the date for the earliest stone tools to 2.6 million years ago (Ma) and the earliest fossils attributable to early Homo to only 2.4-2.3 Ma. By necessity, there’s been increasing openness to the possibility of tool manufacture before 2.6 Ma and by hominins other than Homo.

A series of papers published in rapid succession in early 2015 have solidified these ideas into an emerging paradigm shift in paleoanthropology: the fossil record of the genus Homo now extends back to 2.8 Ma in the Ethiopian Afar; cranial and post-cranial diversity in early Homo is much wider that previously thought, already evincing several distinct lineages by 2 Ma; and Australopithecus africanus and other Pleistocene hominins, traditionally considered not to have made stone tools, have a human-like trabecular bone pattern in their hand bones that’s consistent with tool use.

Now, the Lomekwi artifacts show that those ideas are correct—at least one group of ancient hominin started intentionally knapping stones to make tools long before previously thought. These new archaeological finds are yet another paradigm-shifting discovery from the Lake Turkana basin. This area’s been made famous over the past five decades through the work of the second and third generation of the Leakey family (Richard, Meave and their daughter Louise), and has produced much of the world’s most important fossil evidence for human evolution.

The Lomekwi area where the tools were found had already produced the fossil skull of early hominin Kenyanthropus platyops by Meave and her team. And our West Turkana Archaeological Project has previously discovered the earliest artifacts from the Oldowan culture known from Kenya, and the world’s oldest Acheulean bifaces—considered a kind of “stone Swiss army knife” characteristic of the period.

New find of oldest tools

We dated the Lomekwi 3 tools by correlating the layers of rock in which they were discovered with well-known radiometrically dated tuffs, a type of porous rock formed from volcanic ash. We also could detect the paleomagnetism of the rocks, which in different periods of the past were either normal like today or reversed (the north magnetic pole was at the south pole). These are the standard ways fossils and sites from this time period are dated, and the hominin fossils found just 100 meters from our excavation were dated by another team to the same date.

These oldest tools from Lomekwi shed light on an unexpected and previously unknown period of hominin behavior and can tell us a lot about cognitive development in our ancestors that we can’t understand from fossils alone. Our finding finally disproves the long-standing assumption that Homo habiliswas the first toolmaker.

These tools are unique compared to the ones known from later periods. The stones are much larger than Oldowan tools, and we can see from the scars left on the stones when being knapped that the techniques used were more rudimentary. They apparently required holding the stone in two hands or resting the stone on an anvil when hitting it with a hammerstone. The gestures involved are reminiscent of those used by chimpanzees when they use stones to break open nuts. It is unclear at the moment who the most likely maker of the tools was. We can be fairly certain it was a member of our lineage and not a fossil great ape, as modern apes have never been seen knapping stone tools in the wild.

Our study of the Lomekwi 3 artifacts suggests they could represent a transitional technological stage, a sort of behavioral missing link, in between the pounding-oriented stone tool use of a more ancestral hominin and the flaking-oriented knapping behavior of later, Oldowan toolmakers.

Reconstructions of the environment around Lomekwi 3, based on animal fossils and isotopic analyses of the site’s soil, surprised us too. The area was much more wooded than the paleoenvironments associated with East African artifact sites from later than 2.6 million years ago. The Lomekwi hominins were most likely not out on a savanna when they knapped these tools.

While it is tempting to assume that these earliest artifacts were made by members of our genus Homo, we urge caution. It’s extremely rare to be able to pinpoint what fossil species made which stone tools through most of prehistory, unless there was only one hominin species living at the time, or until we find a fossil skeleton still holding a stone tool in its hand.

Deciphering what the stones say

The Lomekwi 3 discovery raises many new challenging questions for paleoanthropologists. For one, what could have caused hominins to start knapping tools at such an early date? The traditional view was that hominins started knapping to make sharp-edged flakes so they could cut meat from animal carcasses. Maybe they used the larger cobbles to break open animal bones to get at the marrow. While the Lomekwi knappers certainly made sharp-edged flakes from stone cores, the tools’ size and the battering marks on their surfaces suggest they were doing something different as well. And we know they were in a more wooded environment with access to various plant resources. We’re conducting experimental work to help reconstruct how the tools were used.

Another unknown is what was happening archaeologically between 3.3 and 2.6 Ma. We’ve jumped so far back with this discovery, we need to try to connect the dots forward to what we know was happening in the early Oldowan.

Of course, the most intriguing question is whether even older stone tools remain to be discovered. We have no doubt that these aren’t the very first tools that hominins made. The Lomekwi tools show that the knappers already had an understanding of how stones can be intentionally broken—beyond what the first hominin who accidentally hit two stones together and produced a sharp flake would have had. We think there are older, even more primitive artifacts out there, and we’re headed back out into the badlands of northern Kenya to look for them.