This week, the African Development Bank (AfDB), the World Bank of Africa if you like, will elect a new president to replace Donald Kaberuka, a former Rwandan finance minister, who steps down on August 31 after a decade in charge.

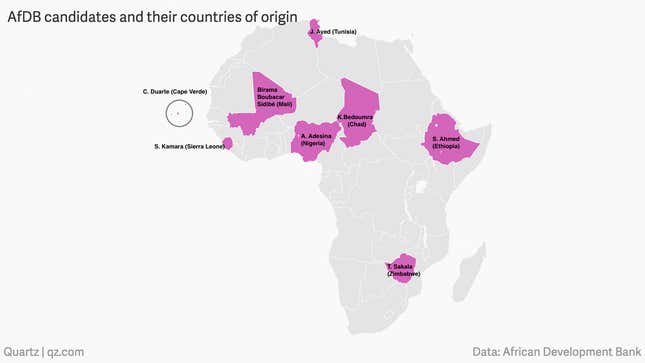

While the race to succeed Kaberuka remains unpredictable, three candidates stand out.

The Nigerian agriculture minister Akinwumi Adesina is considered one of the favorites. Hailing from the largest economy on the continent affords him some cache and influence among member states. With a fondness for bow ties, he has struck a more populist tone, saying the bank needs to be more “inclusive” to ensure the “greatest number” benefit from its $33 billion largesse, with a particular focus on agriculture as one way of doing that.

Cape Verde’s finance minister Cristina Duarte, whose pitch centers around improving the bank’s efficiency and exuding a more focused posture in its investments, has also been touted as a strong contender. The only woman in the race, Duarte has suggested that at times the AfDB’s bureaucracy has been slow in disbursing of funds, impacting the pace of execution of projects. “The bank has limited resources and has to focus on where it has competitive advantage,” she says in her vision statement.

Ethiopia has been one of the fastest growing economies in the region. Sufian Ahmed, the country’s finance minister, and the man who oversaw its growth, is leveraging that fact, giving his campaign significant credibility.

The rest of the field includes finance ministers from Tunisia, Jaloul Ayed, and Chad, Kordjé Bedoumra (former). Samura Kamara, the Sierra Leonean foreign minister is also in contention. Thomas Zondo Sakala, a Zimbabwean and a former vice president of the bank is also in the running. He has the support of South Africa, and the Southern African Development Community (SADC), which could prove useful. And last but not least is the Malian Birama Boubacar Sidibé, the VP of the Islamic Bank of Development, who rounds up a strong group of candidates.

So, what exactly, does the AfDB do?

“The hard stuff,” says Ahmed Salim, an analyst with Teneo Intelligence, a consulting firm. This includes “infrastructure development, energy development, the promotion of energy efficiency and most importantly they have the funds to back their projects,” Salim told Quartz.

Founded in 1964, the bank, funded by member states that includes regional and non-regional actors, has provided loans and grants to countries worth $100.8 billion since its existence, according to data by AfDB.

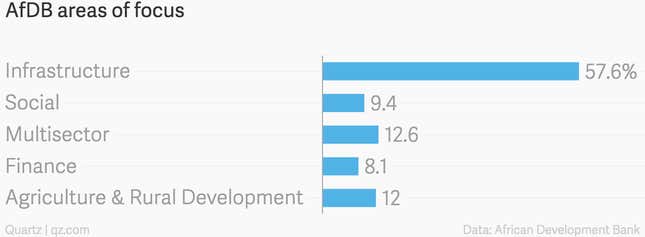

In 2013, the majority of the bank’s funds were dedicated towards infrastructure development, an area that still needs significant investment to unlock the continent’s potential.

“At the heart of the AfDB is the understanding that economic growth in [sub-Saharan Africa] can only be effective through regional economic integration,” Salim says.

Hence, the focus on infrastructure. Earlier this year, the bank facilitated a $123 million loan to the Kenyan government to help finance the Mombasa-Mariakani Highway project, a crucial import/export corridor to the eastern port of Mombasa for the land-locked eastern and central African countries of Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Elsewhere, in Tunisia, the bank provided a $75 million loan to the state-owned energy company backing a gas project in the north African country.

As a financial institution that is less politicized than the other multilateral organizations in the region, such as the African Union for example, the AfDB has been effective in corralling different actors on the continent to finance development projects. “It has been able to leverage the private sector—local, in the sense of African private sector, but also international ones like the Carlyle Group—and the public sector,” says Salim.