The conspiracy alleged today between a global soccer official and sports marketer includes one particularly juicy blind item: A description of an unnamed US multinational sportswear company paying the Brazilian national soccer federation $160 million in 1996 to be their official sponsor—and paying an additional $30 million to a shell company in order to win the contract.

Nike has been the sponsor of Brazil’s soccer federation since 1996, when it reportedly paid about $150 million for a ten-year sponsorship deal that has been criticized for giving the company too much control of the sport there. It was even blamed for the team’s dramatic defeat in the 1998 World Cup final.

“Like fans everywhere we care passionately about the game and are concerned by the very serious allegations,” a Nike spokesperson said in an e-mailed statement when asked if Nike is the company described in the indictment. ”Nike believes in ethical and fair play in both business and sport and strongly opposes any form of manipulation or bribery. We have been cooperating, and will continue to cooperate, with the authorities.”

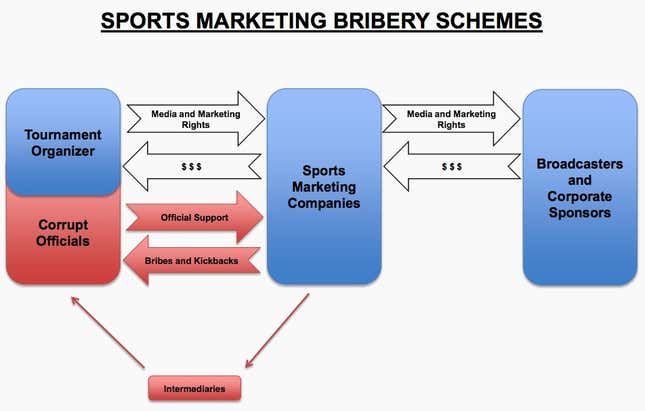

The legal complaint produced by the US Department of Justice describes a scheme between two co-conspirators: José Hawilla, the head of Traffic Group, a Brazilian company that commercialized sporting events on behalf of soccer federations, and the second, a high-ranking official in the Brazilian and South American soccer confederations.

Hawilla previously pled guilty under seal and is presumably cooperating in this investigation; the official is unidentified. The head of the Brazilian federation at the time of this narrative, but unmentioned in the indictment, was Ricardo Teixera, who stepped down from his post in 2012 while facing bribery allegations along with his father-in-law, João Havelange, president of FIFA from 1974 until 1998, connected to the sale of the media rights to World Cups in the 1990s.

The new allegations begin after Brazil’s national team won the 1994 World Cup in the US. A firm listed in the indictment only as “Sportswear company A” inquired about potentially sponsoring the team. The official and Hawilla, as the national team’s marketing representative, negotiated with the company, convincing it to buy out the contract of the team’s previous sponsor.

In 1996, four officials from the sportswear company, Hawilla, and the official met in New York City to sign the primary, $160 million contract for the deal.

But officials from the sportswear company also met Hawilla three days later. Although Traffic already garnered a percentage of the fee directly from the Brazilian federation, the two parties signed a separate contract that described $40 million in additional “marketing fees” to be collected by Traffic on behalf of the Brazilian soccer federation. Over the ensuing years, $30 million was delivered to a Swiss bank account managed by Hawilla, who split the money with the Brazilian soccer official as a kick-back until the contract was terminated in 2002.

The incident is fairly typical of the conspiracies alleged in the indictment—officials, mostly not US citizens, leveraging access to the media and advertising opportunities to benefit themselves and their business partners rather than their soccer organizations. But the involvement of what is apparently a major US company and the US financial system in the corruption gave American law enforcement officials an opportunity to act.

As for Nike, the report certainly puts complaints about its roughshod attempts to gain global domination in perspective. In 1997, a Businessweek article describing how the company elbowed aside Umbro to win the Brazil sponsorship quoted James Gorman, then president of competitor Puma North America.

“Nike is going in and almost encouraging teams to break contracts,” Gorman said. ”Nike will control the soccer world.”