Whenever my mother talks about the career in medicine that she didn’t pursue, I feel guilty twice. Though it was not her intention, I feel guilty for being one of the children who made it unfeasible for her to pursue a profession in which she would certainly have excelled. Then I feel guilty again, because I worry that my own willingness to forego career advancement in favor of family is a sign of betrayal. I do not think my mother regrets having her children but I often think she wanted to have other things more. Acknowledging that for me, becoming a mother is not just one aspiration among many but that it is my highest priority, makes me feel like a traitor.

There are greater numbers of men and women who happily eschew parenthood and its attendant emotional and financial costs every day—and appear to be phenomenally happy for having done so. There are those, too, who casually desire for children as part of an abstract bundle of what a certain kind of modern adulthood looks like: the children appear in this vision alongside a hybrid vehicle, a job with truly flexible working hours, maybe even a vacation home. I know several people who consider children a “nice to have” but would choose professional advancement over parenthood if forced to pick. I find all of these choices and the variations in between to be evidence of progress in our cultural relationship with womanhood, an improvement over a past that produced far too many unwanted children and their unhappy, overworked mothers.

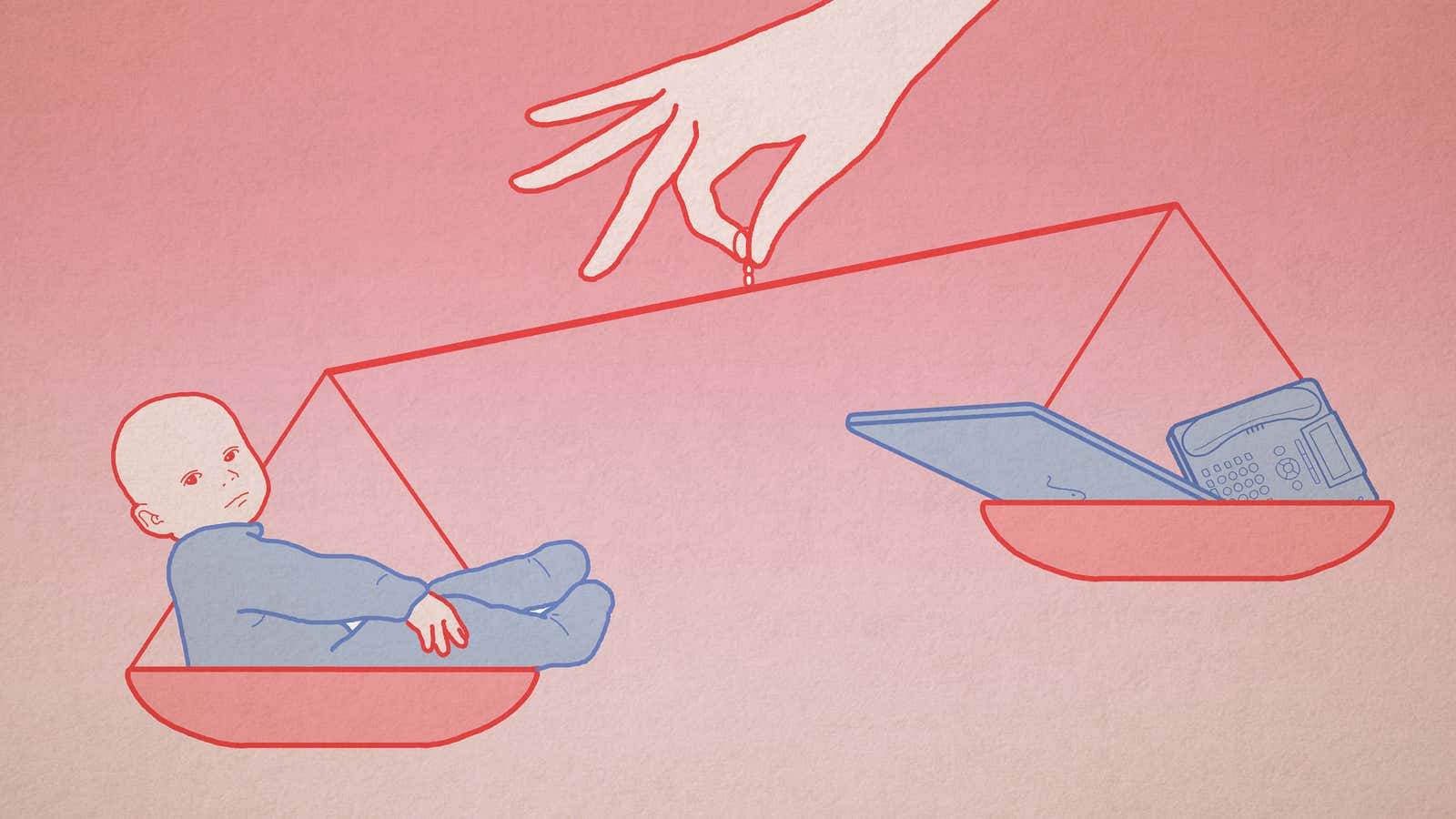

But among my generation in particular, there has developed an expectation that educated, career-oriented women deprioritize motherhood. We are allowed to want children so long as we also want other things, like an impressive career, a supportive partner, and a handful of interesting hobbies that keep us sufficiently dynamic and social. This, society tells us, is to prevent us from becoming one of those women who only cares about her kids. I absolutely want all of those things, and in a perfect world, there would be no conflict between them. But I know enough about what brings me joy, as well as what I’m actually good at, to know that being a mother is more important to me than anything else.

Admitting this has the attendant risk of seeming desperate. We are allowed to see a cute child and say something jocular like, “My ovaries are exploding!” but expressing anything more sincere makes us seem a bit tragic. I am always hesitant to share that no, really, I can actually physically feel my desire to be a mother. It seems creepy to say so, and I also don’t want to contribute any fodder to the tired notion that all women share the same biological imperatives.

This is about care, not procreation. It is not an aching ovary but a sudden physical tranquility when caring for children or even just holding a baby or seeing one smile.

When I say that I want children, I don’t just mean that I want to become pregnant and have a baby. Babies are some of my favorite people, but I can just as easily imagine adopting an older child as gestating a brand new one. I selfishly want to experience the profound love I’m told comes with having a child. But I also consider taking on the responsibility of raising a virtuous, kind person to be as noble and demanding a pursuit as ones related to career, romance, travel, and finances.

Why is this pursuit as one’s highest priority seen so often as quaint, simple-minded even? It’s unfortunate that we simultaneously valorize motherhood as the achievement of a woman’s highest purpose, but portray too strong a desire for it is as pathetic.

I make a decent portion of my income writing articles wherein I posture the kind of independence and take-no-nonsense attitude that some see as antithetical to being tied down by children. Underlying this assumption is a belief that women are one-dimensional caricatures who are either well suited to mothering by virtue of their domesticity and gentleness, or too disastrously selfish for the stuff. I don’t imagine myself becoming a woman who talks almost exclusively about her children or only befriends fellow parents. But I find our collective disdain for these mothers troubling. While there are certainly those who rudely redirect conversations about other things back to their offspring, for the most part, these women are just sharing what brings them joy.

I do hope that I won’t have to surrender one hope in pursuit of another. I also realize this hand wringing might be over nothing if I never end up with the right finances and/or partner to even make children a possibility. But I am tired of hearing people tell me what a “waste” it would be if I sacrificed my career for potential children. I realize such comments are meant as compliments, but more than anything, they betray just how much we undervalue the physical and emotional labor and indeed, the talent, that goes into parenting.

My mother did not “waste” her intelligence and hard-won education during the years when she was at home with her daughters. Her intellect was instrumental to imbuing us with intellectual curiosity and a sense of wonder at the world that made us high-performing students and interesting women. Her gentleness informed my sense of empathy and perhaps my current desire to nurture. And in the end, her disappointment that she could not do everything she wanted has made her the most ferocious advocate for me prioritizing my own dreams—whatever they may be.