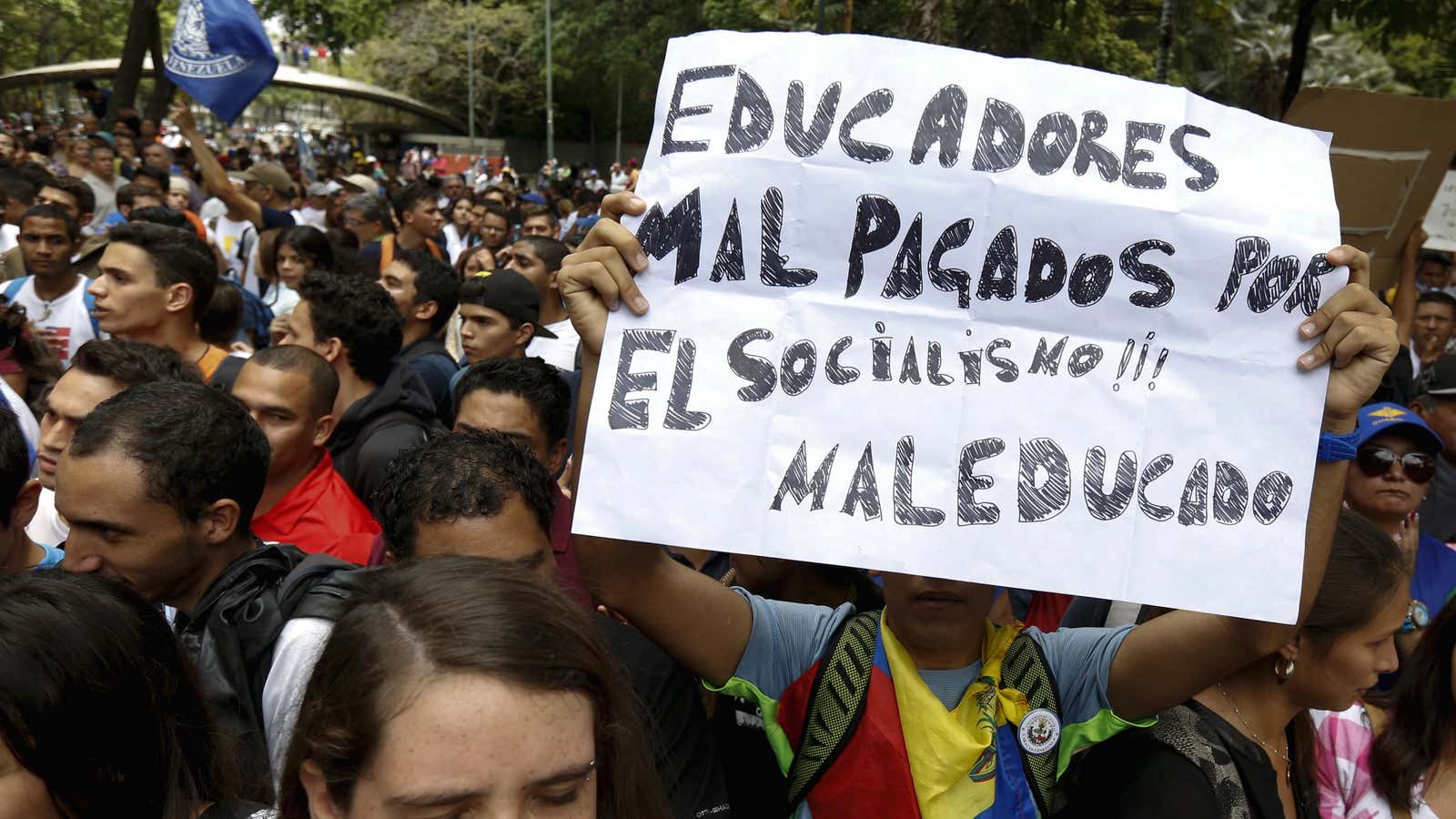

Last Thursday, May 28, students and university professors took to the streets of five cities across Venezuela to demand better working conditions and salaries for educators. Also on their list of demands were an increase in the higher education budget, greater safety on university campuses, and respect for the autonomy of universities.

The protests follow the recent announcement by the Venezuelan government that all university places are now to be assigned by the National Intake System, which is under control of the University Education Ministry.

Up until now, 30% of places were assigned by the government agency Oficina de Planificación del Sector Universitario (OPSU), with the remaining 70% being left to the individual admission procedures of each university.

The National Intake System will henceforth be used by all public higher education institutions to award 100% of their places. The measure has widely been rejected as unjustly overriding the ability of public universities to choose their students for themselves.

In the process of assigning students places, multiple variables will be taken into account which previously weren’t considered during the selection process, such as where the would-be student lives and their socio-economic status.

University education minister Manuel Fernández told press that 70% of those students that are to enter public universities now must have graduated from public high schools, leaving only 30% of places to those who studied at private establishments. Fernández described the new quota system as “a democratization of the intake.”

The minister recalled that up until 2014, 97.5 % of the assignment of places depended on academic records, and explained that, the system will now take into account four variables: 50% of weighting will be given to academic record, 30% to socio-economic conditions, 15% to where the student lives, and 5% to “citizen participation”—if students have taken part in community service.

The changes will mean that those applicants not from lower-middle or lower class backgrounds will have less chance of securing a university place.

The secretary of Venezuela’s Central University, Almalio Belmonde, rejected the new system and argued that it represents a strategy by the government to “monopolize the assignment of places for strictly ideological reasons … only the academic record is relevant, the rest of the variables are politics, pure and simple.”

The government’s move disregards several Venezuelan legal precedents, such as the 1958 University Law, which establishes that universities alone are “empowered to set class sizes and regulations of professional courses proposed by university councils, and to recommend suitable procedures for the selection of prospective students.”

Moreover, Article 109 of the Constitution “enshrines university autonomy to plan, organize, elaborate, and update programs of research, teaching, and outreach. It establishes the inviolability of the university campus. National research universities will exercise their autonomy in conformity with the law.”

The rector of El Libertador Research University (UPEL), Raúl López Sayago, explained that the admission procedures of universities are currently based on scientific criteria.

“The university never wants to exclude anyone; what we want to do is guarantee that once the intake is made students pursue their studies and graduate successfully … not everyone can be a doctor, not everyone can be an engineer or a teacher, so we need to examine the profile and characteristics of applicants so they can develop successfully in a university course,” he explained.

Demands without answers

Students and professors alike showed their anger with the new decision, as well as the neglect of Venezuela’s university system in general, by protesting on Thursday against the decisions and failures of the Ministry of Popular Power for University Education.

Despite officers of the National Bolivarian Police (PNB) and the National Bolivarian Guard (GNB) blocking the protest from reaching the ministry, minister for university education, science, and technology Manuel Fernández himself made an appearance at the protest.

In Venezuela, the university sector is going through a labor and salary crisis. Recent announcements by president Nicolás Maduro that the national minimum wage would be increased only enraged professors further, as the average monthly salary for a new higher education teacher is now less than the minimum wage.

Class dismissed

Many university courses in Venezuela are now in “technical closure” due to the scarcity of basic resources for laboratories. The president of the Professors’ Association of the Central University of Venezuela (UCV), Víctor Márquez, explained that several faculties within UCV are struggling to keep going, among them the science and dentistry schools.

“They don’t have materials to practice with. Multiple postgraduate courses in dentistry have had to close. It’s a problem that goes beyond the union’s struggle,” Márquez said.

On Thursday, president of UCV’s Federation of University Centers (FCU), Hasler Iglesias, reported that the shortage of basic materials is set to prevent students from finishing this semester, as they can’t fulfil the necessary practical study components of their courses.

On May 4, the Dentistry Faculty of the University of Carabobo (UC) declared itself in “technical closure” due to lack of resources. The situation forced professors to suspend classes “until further notice.”

Translated by Laurie Blair.