Skipchen, a café on a busy Bristol thoroughfare, has been packed every lunchtime since it opened in October last year, serving up to 200 meals a day. Today, the team is taking its concept on the road, setting up shop at festivals in Scotland and elsewhere on the way. They’ll be back home in the autumn, honing an offer that’s proved popular across the country: sourcing most of what they serve from the mountains of food wasted by supermarkets, wholesalers, and restaurants.

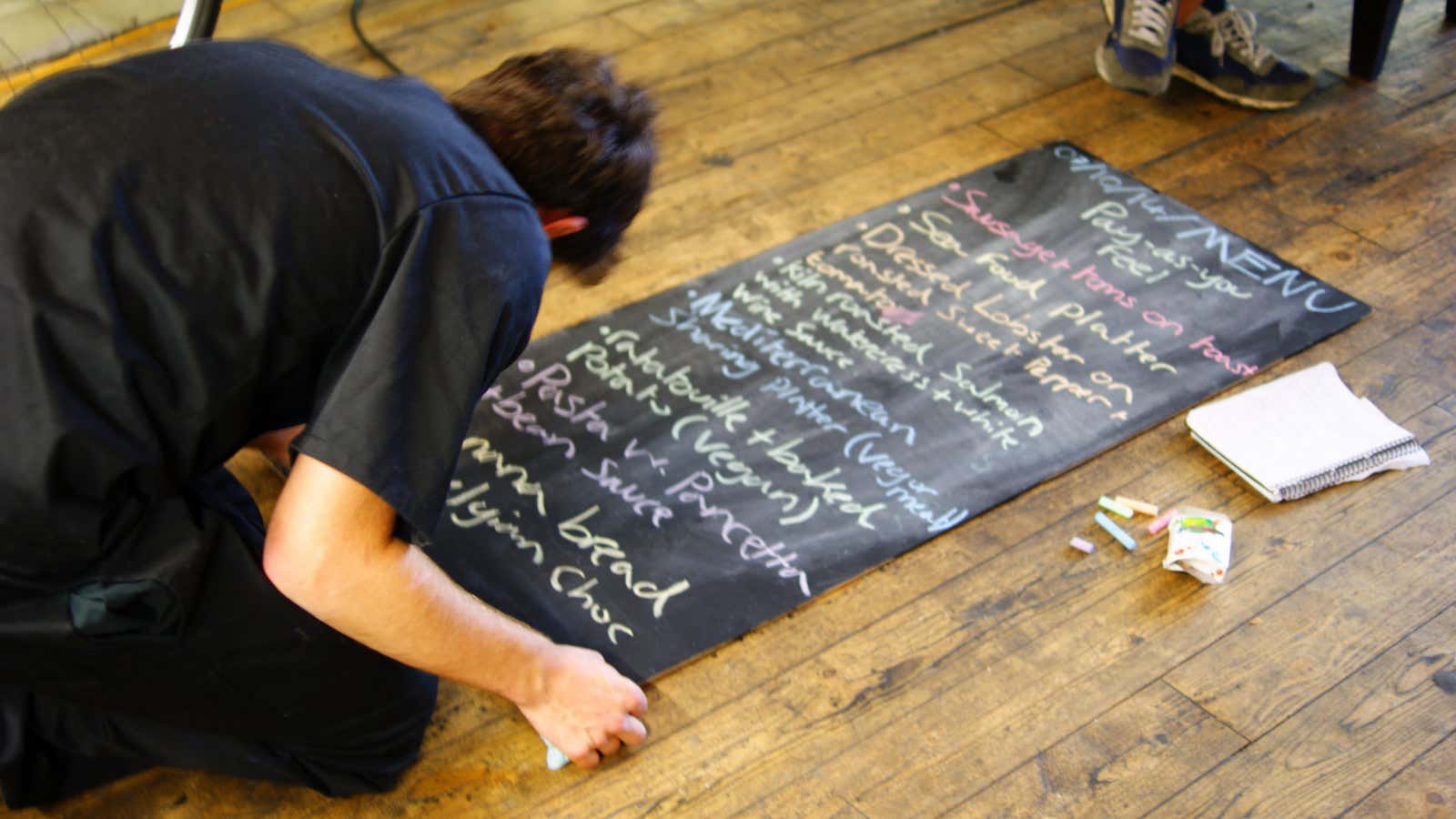

There are now 14 cafés with the same idea in cities like Leeds and London, and up to 80 at various stages of the development process. The umbrella that ties them together is The Real Junk Food Project, a grassroots organization that started in Leeds. The cafés are autonomous but share certain characteristics: they plan their meals based on what ingredients they find each day; and there are no fixed prices, allowing customers to pay what they feel a dish is worth.

The movement is about “addressing the culture of waste” that pervades modern society, says Sam Joseph, a 25-year-old Environmental Conservation graduate who with Katie Jarman and others set up Skipchen.

The issue of food waste has risen to prominence in recent weeks, since France imposed a ban on supermarkets throwing away food that’s still edible. Joseph welcomes the increased interest, but tells Quartz that targeting supermarkets and insisting on redistribution is only a “patch” on the problem of overproduction, and the demand that modern methods of farming and trade have fostered for near-infinite choice.

A year that’s bad for growing pumpkins but good for cauliflowers in the UK, for example, is a waste-creation disaster, where “loads of cauliflowers are getting plowed into the ground, and loads of pumpkins are getting imported from South America,” Joseph says.

He notes that there are situations, like at high-end restaurants, where customers are happy for their choice to be restricted to what is seasonal or fresh—as Skipchen and others waste-food cafés also do. But in grocery stores, less variety is anathema to most buyers.

Even the most ethical consumers he knows, Joseph says, “still kind of hate it” when supermarkets run out of watercress or fresh prawns. It’s a culture The Real Junk Food Project wants to change.

“We’ve lived out of supermarket bins for years,” said Joseph, who learned to cook by scavenging a wide range of quality ingredients including meat, seafood, vegetables, rice, milk, and eggs thrown away by Waitrose, an upmarket grocery chain.

Today, grocery giant Tesco announced a trial to give away food rather than discarding it. The company admitted that it threw away 55,400 tonnes (61,070 short tons) of food in the past year. Charities can only absorb so much of this—Skipchen and projects like it want to fill the gap by convincing diners to see it not as rubbish, but as nourishment.