The planet’s second-most-famous dinosaur of all time is probably best known for its horns—its name, in fact, means “three-horn face.”

But triceratops should be famed for its teeth. Just-published research (paywall) reveals that its pearly whites are more complex than those of other dinosaurs—and of any mammal or reptile living today. This sophistication helped it mow through dense shrubbery like a seven-ton Morrissey hitting a salad bar.

Here’s a short clip the research team made explaining their discovery:

Though reptiles have been evolving for more than 300 million years, their teeth are still a little backward, at least compared to mammals. Sometimes pointy, sometimes flat, reptile choppers are generally good for grabbing morsels of food and crushing it. Some species’ teeth barely meet, or don’t meet at all when they close their mouths—think of the fangy grin of a crocodile, for instance. That means most reptiles can’t grind their meals.

Not so for herbivorous mammals. The way their teeth meet allows them to slice and shear from different angles, and chew denser tissues. The way their teeth hollow out over time is another big gain in efficiency. By limiting the surface area, the self-wear process reduces friction between the teeth and the plant matter the creature was eating.

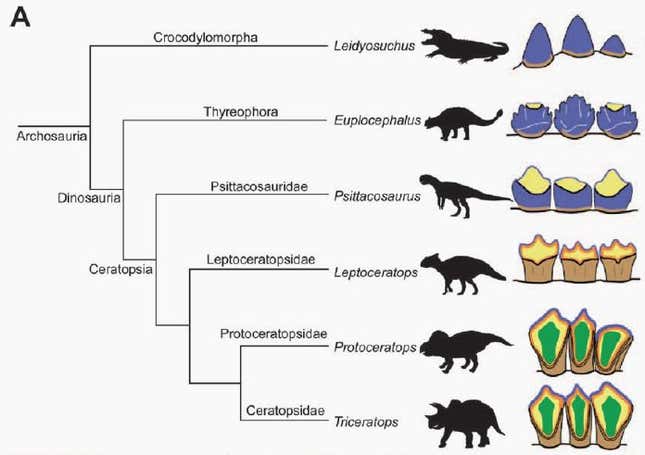

The tissues that make up the tooth are critical to this filing process. Up until now, scientists have credited horses and bisons with evolving the more sophisticated teeth. And sure enough, these grassland gobblers have four layers of tissue. Reptiles have just two.

But triceratops? Count them—five layers of tissue:

After building a fancy 3-D model of triceratops teeth, the scientists found that the distinctive way each of these tissues wore created a highly intricate topography. The resulting pressure variations let triceratops ”split, crush, and drive fissures through food,” as the scientists put it.

The evolution of such exceptional teeth, say the researchers, may have played a big role in helping triceratops diversify its diet, which likely ranged from ferns to smallish palm trees. That’s a pretty critical adaptation for a vegetarian hulk like triceratops. At around 30 feet (9 meters) long, 10 feet (3 meters) tall, and weighing between six and 12 tons (5.4-10.8 tonnes), triceratops had to chow down on a huge volume of plants just to survive. That’s why the researchers think that the key to triceratops’ domination of the forests of the Late Cretaceous period was likely its super-spiffy teeth.