The disturbing signals behind China’s steep drop-off in borrowing from foreign banks

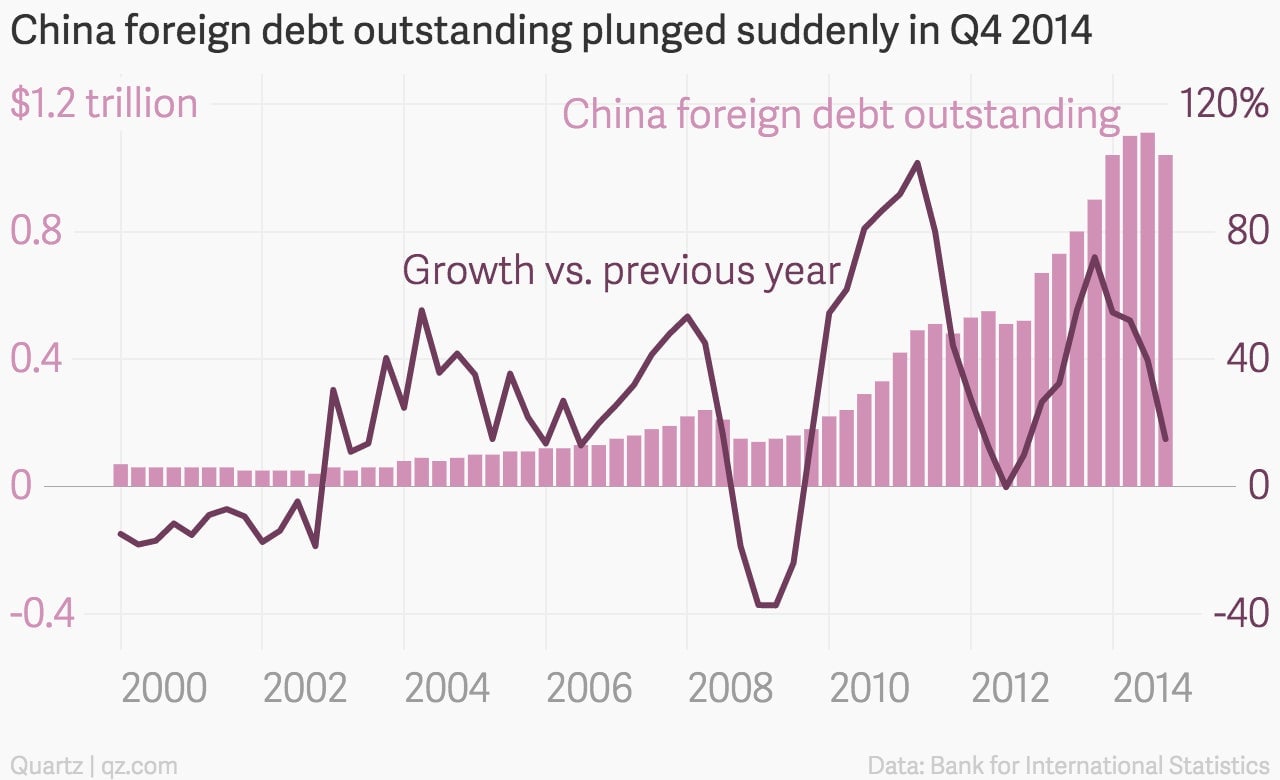

China’s recent explosion of foreign borrowing appears to be reversing. According to just-released data (pdf) from the Bank of International Settlements, China’s outstanding overseas debt shrank abruptly in the last quarter of 2014. It now stands at just more than $1 trillion—about $51 billion less than in the third quarter—making the People’s Republic the eighth-biggest borrower of international debt.

China’s recent explosion of foreign borrowing appears to be reversing. According to just-released data (pdf) from the Bank of International Settlements, China’s outstanding overseas debt shrank abruptly in the last quarter of 2014. It now stands at just more than $1 trillion—about $51 billion less than in the third quarter—making the People’s Republic the eighth-biggest borrower of international debt.

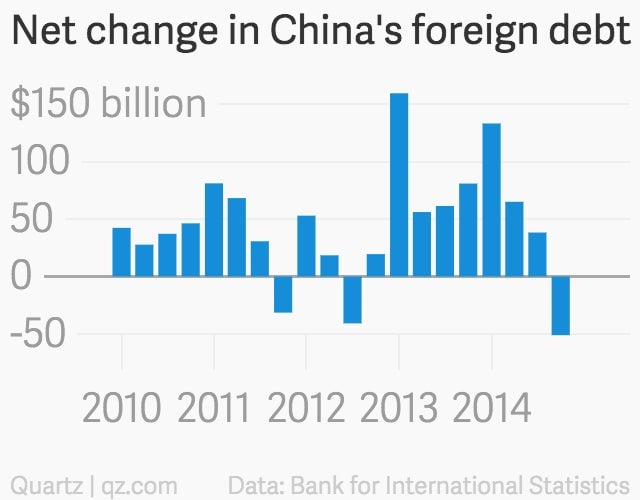

The fourth-quarter drop-off in foreign lending is the second-biggest quarterly decline on record, after 2008’s giant fourth-quarter drop accompanying the global financial crisis. The recent decline puts an end to what had been a surge in overseas bank credit that began in 2013.

What’s behind the steep drop?

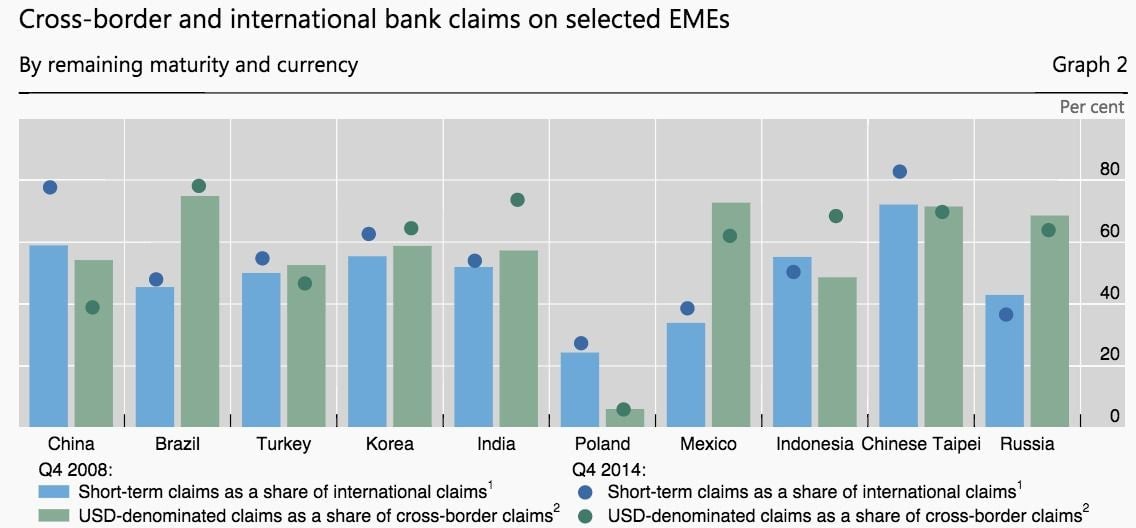

Here’s one clue: As the BIS notes, the eruption of global credit to China in the last few years has mainly been in short-term lending—financing that matures in three to six months. In last year’s fourth quarter, nearly 80% of claims on China were for short-term debt, up from 59% in the fourth quarter of 2008.

Short-term finance is often commonly used to finance trade—a stop-gap cash source for exporters and importers. (That’s why demand for foreign loans leapt when China’s joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.)

It can also be used to finance fake trade. And until very recently, that was happening in a big way in China.

Throughout 2013 and early 2014, as the yuan steadily rose against the dollar, clever traders falsified trade orders to borrow from in dollars from Hong Kong banks. They then switched the dollars to yuan, often re-lending out the amount via shadow banking products, at a much higher interest rate than the original Hong Kong loan. By the time the loan came due, they’d have turned a tidy profit. The trade is self-reinforcing; the more people swap dollars for yuan, the faster the yuan appreciates.

The “carry trade,” as it’s often called, was lucrative as long as the yuan was appreciating. But when Chinese companies started believing the yuan will fall, they bought dollars instead.

The yuan is loosely pegged to the US dollar. And when the greenback started strengthening against other major currencies in mid-2014, Chinese traders bet that the People’s Bank of China would stop letting the yuan grow along with it. Since they were trading their yuan back into dollars, they didn’t need to borrow new dollars from foreign banks in Hong Kong anymore.

Though the BIS data are fairly delayed, they’re another sign that capital has been flowing out of China.

As we explained last year, “capital flight” doesn’t pose the same problems for China as it has in the past for, say, Argentina or Thailand. It still poses problems, though. With so many Chinese companies struggling with debt, new money is critical to keeping them alive.

Overseas banks have been increasingly important sources of liquidity for China’s financial system. The BIS data suggest that an important channel of money creation has been drying up.