The international community has a pretty standard prescription for poor countries: Leverage development aid, attract foreign investment, and earn your way into middle income.

But the other side of the equation is that the international financial system makes it quite easy for bad actors in those countries to make off with the cash aimed at bolstering public prosperity, slipping it out of the country illicitly through trade fraud and secret bank accounts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the poorest countries in the world see the biggest relative illicit outflows, according to a new study from the NGO Global Financial Integrity that provides a glaring example of how futile these efforts are without more attention to illicit financial flows.

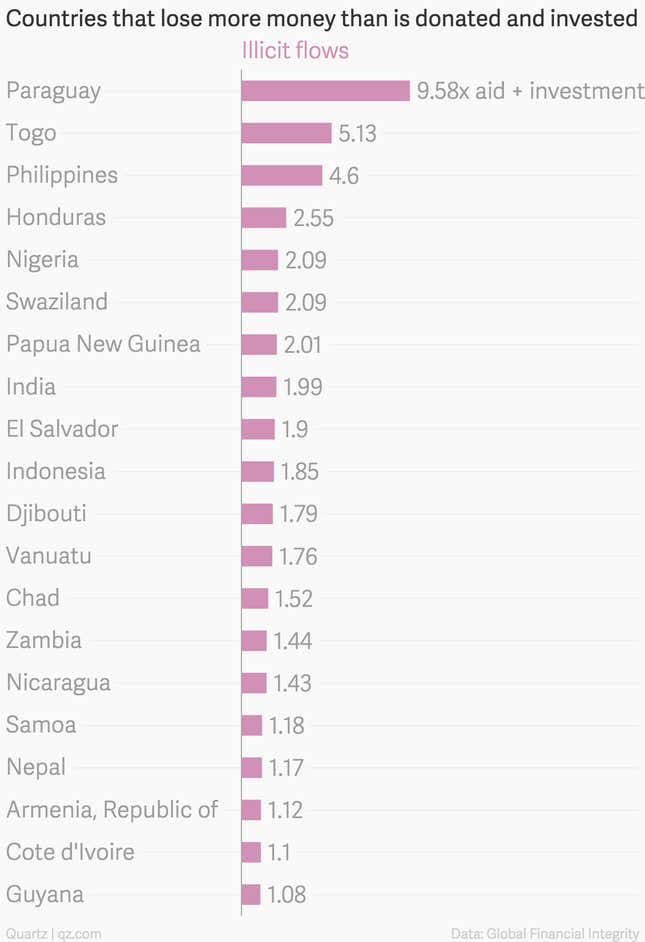

For example, here are 20 countries that see much more money slip out through their borders than comes in via official development assistance and foreign direct investment combined between 2008 and 2012:

So for every dollar invested or donated to, say, the Philippines, almost $5 leaves the country illicitly. That’s not exactly a recipe for development.

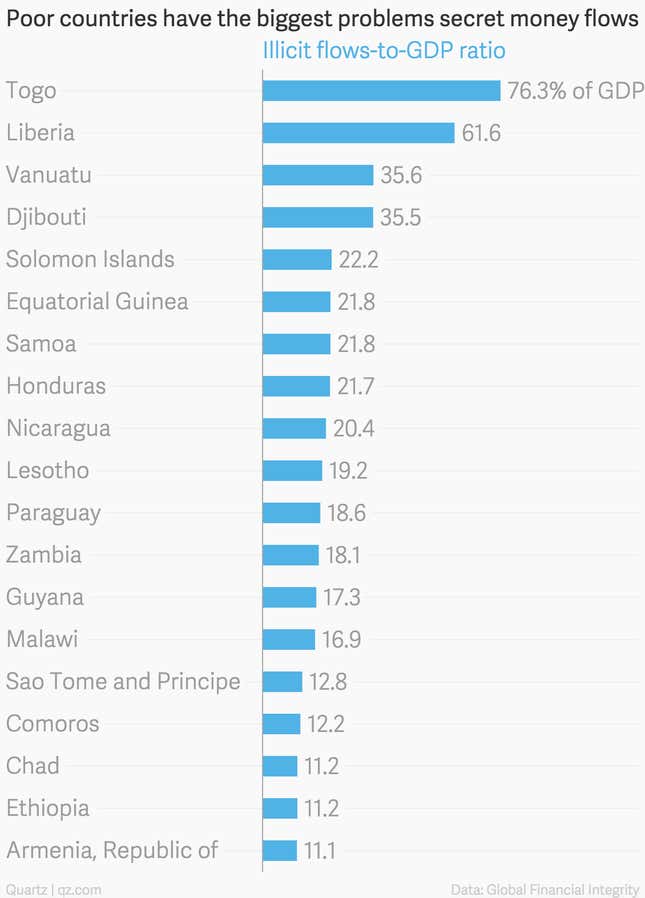

Or take this table, which shows that of the 82 lowest-income countries, twenty see funds equivalent to more than 10% of their annual economic production leave the country illicitly:

Corrupt officials and lax customs practices are part of the problem in these countries, but every transaction takes two parties, and advanced economies, including the United States and the European Union, are not taking the steps needed to make it harder for people to launder money in the international financial system. GFI’s leadership criticized global leaders for failing to even deploy tougher rhetoric at the recent meeting of the G-7 economies.

“We are very disappointed in the G-7’s inaction on the issue of illicit financial flows,” GFI Managing Director Tom Cardamone said in a statement. “Failing to take a strong position on illicit flows—the most damaging economic problem plaguing the developing world—is a huge opportunity missed.”