By now, most social-media savvy people have seen or heard about the artist Richard Prince and his “New Portraits” Instagram gallery. If you haven’t, basically Prince has taken screenshots of other people’s Instagram photos, blown them up into huge 6-foot tall inkjet prints, and sold them for nearly $90,000 each at the Frieze Art Fair in New York City.

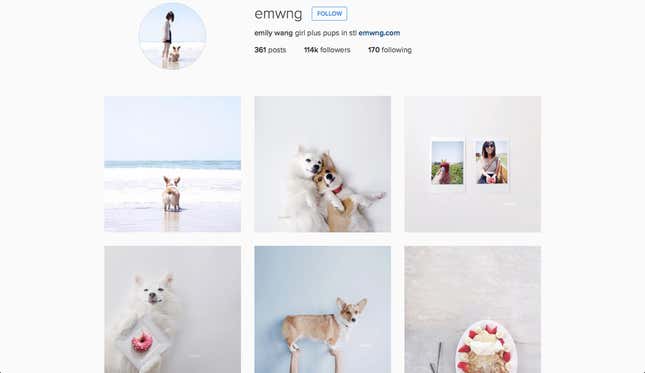

As a photographer on Instagram, the story struck quite a chord. A large part of what I do in my free time includes creating unique content with my dogs for my Instagram account. What started as a casual hobby, however, eventually landed me a full-time job at Nestle Purina Petcare in a social media management and content creation position.

The road to this breakthrough was definitely not an easy one, and it reveals a lot about the ways Instagram’s privacy policies don’t protect many of its users the way they probably think they do. About two months after starting my Instagram account, I discovered one of my followers was stealing my photos and photoshopping her dog in place of mine. I contacted the Instagram team countless times about the problem, but was met with less than helpful responses: “Having reviewed your claim, we don’t see how the content you’ve reported, used in the manner depicted, could constitute a violation of your rights.”

How could it constitute a violation of my rights? To me, the violation was as plain as the screenshots of my manipulated and stolen images I had sent to the Instagram team.

Instagram claims that, “On the platform, if someone feels that their copyright has been violated, they can report it to us and we will take appropriate action. Off the platform, content owners can enforce their legal rights.” I was eventually able to get most of the stolen photos taken down—but it required months spent reporting each and every incident to Instagram. This is of little comfort to the users in the Richard Price case, however, who did not have their work reposted on the platform. Instead, these unlucky few found their work being sold without their permission in an offsite gallery, outside the purview of the social media platform.

Looking back, was my career advancement affected by others copying my work? Probably not, actually. But it would have mattered a lot more if I had been a self-employed freelancer. I have also dabbled in freelance content creation, and am still paid to partner with and create content for companies and brands. At the end of the day, my authenticity, originality, and value could be undermined by others copying or recycling my work elsewhere.

All this goes to show that there are still so many grey areas when it comes to intellectual property and ethics. Instagram of course is a company. It makes its money off of its users, and in turn some of its users make money off of being a part of its communities.

A minority of social network users take copyright infringement more seriously than others. This is understandable—putting aside the injustice of having your property stolen or repurposed, artwork and photography can be extremely personal in nature. I know of a photographer who discovered photos of her dog and baby were stolen from her Instagram and used by a company in Hong Kong for marketing purposes. Photos of her child were being used, without permission, to sell a company’s products. Talk about an extremely invasive, frustration experience.

Others, like popular pin-up model site @Suicidegirls—one of the Instagram accounts Prince used in his art show—have more of a “What can I do anyway?” attitude.

For me, Richard Prince’s story reveals a larger problem with social media today: technology is progressing far faster than the pace of policymakers, an especially frustrating phenomenon for those in the artistic or creative fields. A similar case study may be the current disruption of the transportation industry created by ride-sharing companies like Uber. Uber has been able to take advantage of loopholes in outdated transportation laws originally designed to protect taxicab drivers and customers.

Like Richard Prince, the Instagrammer who stole my photos and reposted them existed in something of a grey area, where ethical mores are not necessarily supported by public or even corporate policy. As Jose Pagliery wrote for CNN Money recently: “You forfeit certain rights by using a social media network. And once your photos are out in public, they’re out of your hands forever.” My story has a happy ending, at least, we clearly still haven’t totally figured out how to regulate technology that is rapidly changing the ways in which we interact with the world—and the world interacts with us.