Art is seen as unquantifiable. Great paintings are creative forces that transcend their brush strokes, colors, and compositions. They can’t be reduced to mere data, analyzed, and ranked by their creativity. Two computer scientists at Rutgers University respectfully disagree.

Ahmed Elgammal and Babak Saleh created an algorithm that they say measures the originality and influence of artworks by using sophisticated visual analysis to compare each piece to older and newer artwork. They worked from the premise that the most creative art was that which broke most from the past, and then inspired the greatest visual shifts in the works that followed.

They did it by looking specifically at qualities such as texture, color, lines, movement, harmony, and balance. “These artistic concepts can, more or less, be quantified by today’s computer vision technology,” they write in their paper “Quantifying Creativity in Art Networks” (pdf).

Their experiment—which involved two datasets totalling more than 62,000 paintings—was entirely automated. They gave the computer no information about art history. Yet what they found was that their algorithm often came to same conclusions as art experts. ”In most cases the results of the algorithm are pieces of art that art historians indeed highlight as innovative and influential,” the authors wrote.

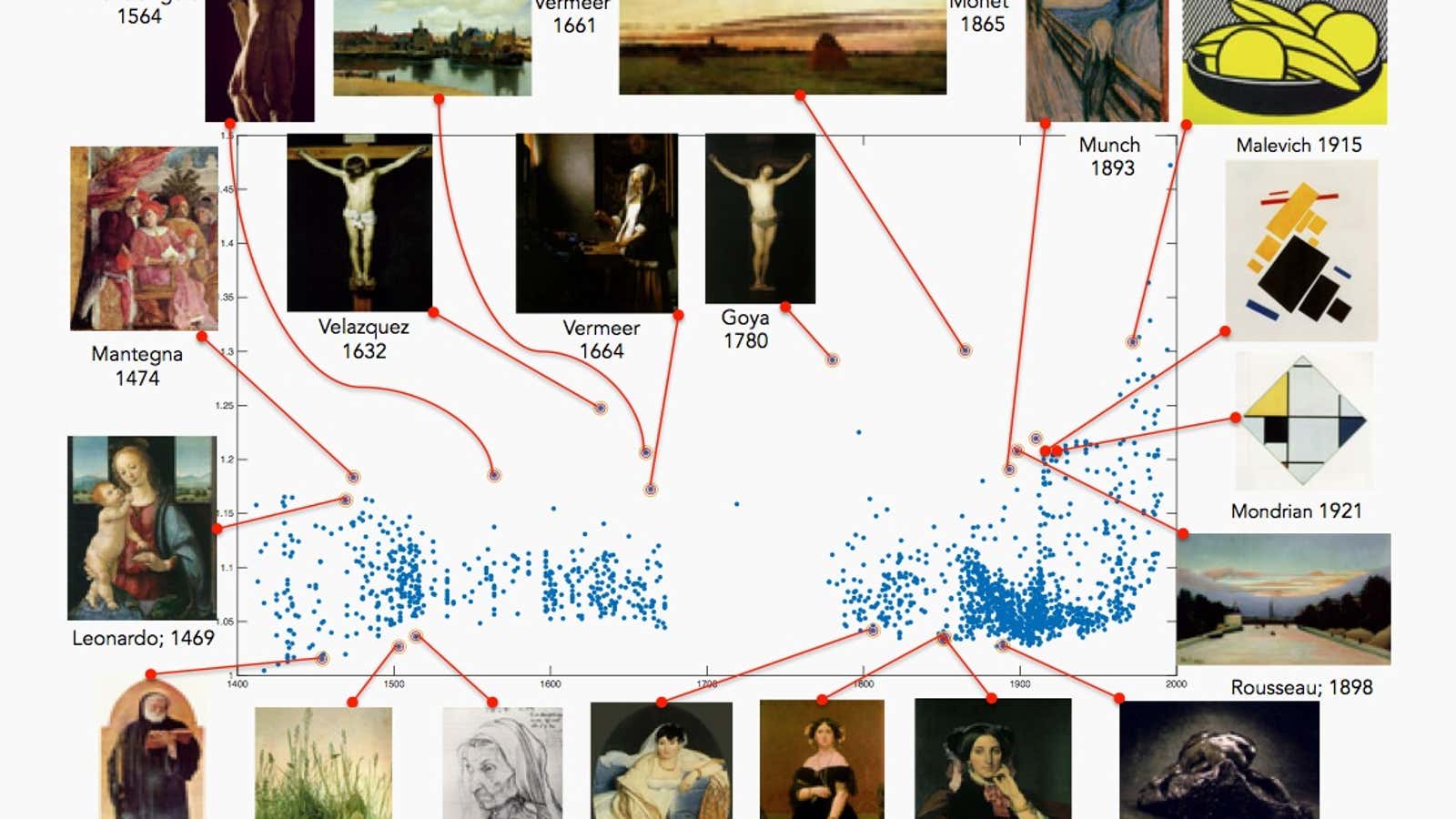

One chart in the paper laying out the scores of 1,710 paintings available on Artchive.com pinpointed works by renowned artists including Velazquez, Goya, Monet, and Lichtenstein as being among the most creative.

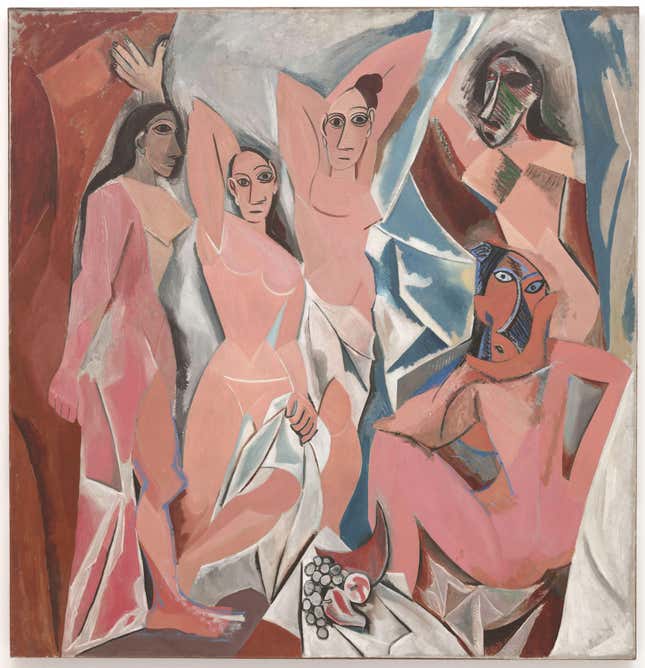

Analysis of another dataset ranked paintings by Picasso as among the most creative in the early 20th century—Les Demoiselles d’Avignon had the highest score between 1904 and 1911. After that, the “majority of the top-scoring paintings between 1916 and 1945 were by Piet Mondrian and Georgia O’Keeffee,” the paper said.

The algorithm has its limitations. The authors note their analysis is restricted to paintings, and some sculptures, that were readily available online. Although the authors expect that to change as more art collections are digitized.

But a point the authors don’t address is that their algorithm is looking at flat, digital, 2D images of real-life, 3D objects from a single point of view, and they’re all reduced to a scale that fits into a computer screen.

As good as a picture is these days at capturing the minute details of paint and other media layered on canvas, it still doesn’t replicate the experience of standing in front of actual paintings, which range widely in their dimensions, and viewing them from different angles, from different distances, to appreciate them fully not just as representations but as objects. That experience is a very real part of judging an artwork’s originality and influence.

Their algorithm is impressive, and useful in some regards. But it isn’t replacing human critics, at least not yet. Not that they want to. ”Our goal is not to replace art historians’ or artists’ role in judging creativity of art products,” the authors insisted.