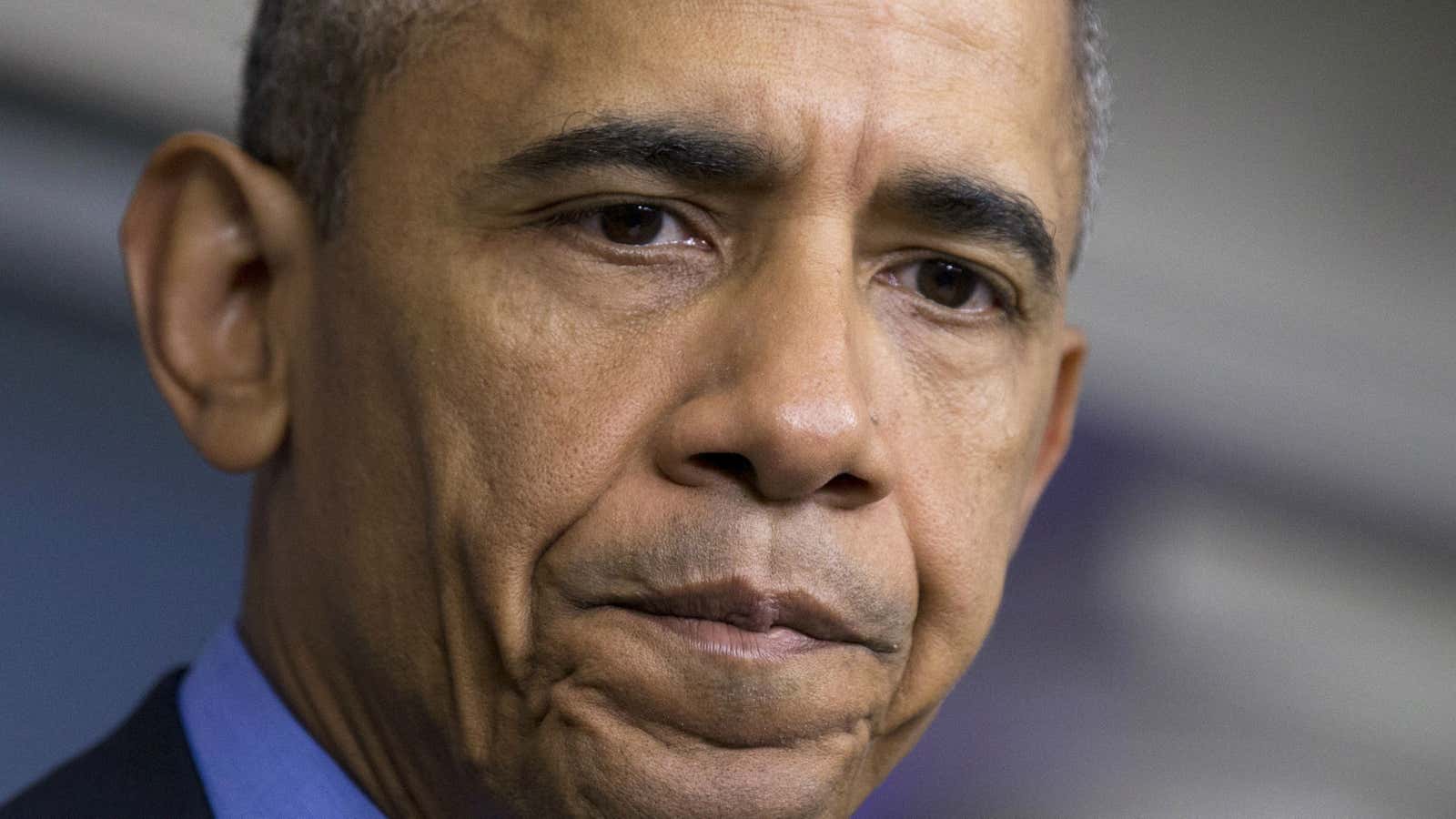

On Friday, the comedian Marc Maron interviewed president Barack Obama in his Los Angeles garage studio, for an episode of his popular podcast, “WTF with Marc Maron.” Maron generally hosts comedians, actors, and writers on his show, and connects with his guests on raw, human terms, discussing topics such as heartbreak, addiction, anxiety, and personal failures and successes.

He covered a bit of personal ground with Obama too, but he also asked him, in the wake of last week’s shooting in Charleston, as well as the police actions in Baltimore and Ferguson, about where we stand today when it comes to race in America.

Much has already been made of the president’s use of the N-word in this context, although it appears multiple times in his book, Dreams from my Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. But as Obama argued, seemingly dropping the N-word in passing, the sort of overt racism embodied by such language (which was used by US presidents Truman, Johnson, and Nixon) is not the point. The insidious, damaging, systemic legacy of racism—and the inequalities and injustices that persist—are what he is more interested in addressing.

Here’s what Obama said:

Obama: First of all, I always tell young people in particular, do not say that nothing has changed when it comes to race in America, unless you lived through being a black man in the 1950s or 60s, or 70s. It is incontrovertible that race relations have improved significantly during my lifetime and yours, and that opportunities have opened up, and that attitudes have changed. What is also true is that the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, discrimination, in almost every institution of our lives, that casts a long shadow, and that’s still part of our DNA that’s passed on. We’re not cured of it.

Maron: Racism.

Obama: Racism. We are not cured of it. It’s not just a matter of it not being polite to say nigger in public. That’s not the measure of whether racism still exists or not. It’s not just a matter of overt discrimination. Societies don’t overnight completely erase everything that happened two to three hundred years prior, and so what I tried to describe in the Selma speech that I gave commemorating the march there was again a notion that progress is real and we have to take hope from that progress but what is also real is that the march isn’t over, and the work is not yet completed. And then our job is to try in very concrete ways to figure out, what more can we do? So let’s take the example of police practices. Cops have a really tough job.

Maron: Yup.

And part of the reason cops have a tough job, particularly in big cities, is that there are communities that are poor, are systematically locked out of opportunity, that suffer from legacies of discrimination that have been built up over generations, and we send cops in there basically to say, keep those folks from making too much trouble.

Obama went on to discuss possible ways to “break the legacy of racism and poverty,” including joining activists and police on community task forces, and improving early childhood education in the lowest income communities.

“What hasn’t happened,” said Obama, “is us making a collective commitment to do it.” He went on:

The point I’m making is when you look at how to deal with racism, how to deal with issues of some of the police shootings that have been involved, I’m less interested in having an ideological conversation than I am looking at what has worked in the past and applying it, and scaling up. What is required is a sense on the part of all of us that what happens to those kids matters to me, even if I never meet them, because my society is going to be better off, I’m going to feel better about the America I live in, and over time I’m confident that my children and my grandchildren are going to live a better life if those kids also have opportunity. That’s where we have to feel hopeful, rather than to say that nothing has changed, we have to say, “Wow, we’ve actually made significant progress over the last fifty years.” If we made as much progress over the next 10 years as we have over the last 50, things would be better. And that’s within our grasp, it’s available to us. And this is where, again, you want to get to those decent, well-meaning Americans who would agree with that, but when it gets translated into politics it gets all confused. And trying to bridge that gap between the good impulses of the overwhelming majority of Americans and how our politics expresses itself, continues to be the biggest challenge.