Now that months have passed and I’m basking in our summer sun, I can safely confess that I had a miserably unhealthy winter.

It started in November with my first ever broken bone, a silly bike-vs-oil-patch accident which broke my clavicle and brought me surprisingly distressing pain for more than a month. But far worse was when I was diagnosed with asthma last December and needed two inhalers to breathe better.

It started insidiously, when I began to wake up deep in the night with achy chest pains. I initially thought it was just rib bruising from my bike tumble, but then I also started feeling short of breath. One morning I woke up suddenly gasping for air, and I finally went to a colleague at my clinic. My chest x-ray was normal but I took a breathing test which showed my lung function only 60% of normal, and she said I probably had asthma. I’ll never forget those moments after taking those first two puffs of albuterol: in just a few minutes, that elephant-like pressure on my chest for a month quickly lifted away, and I filled my lungs with precious, polluted Beijing air. Its acrid smell never tasted sweeter.

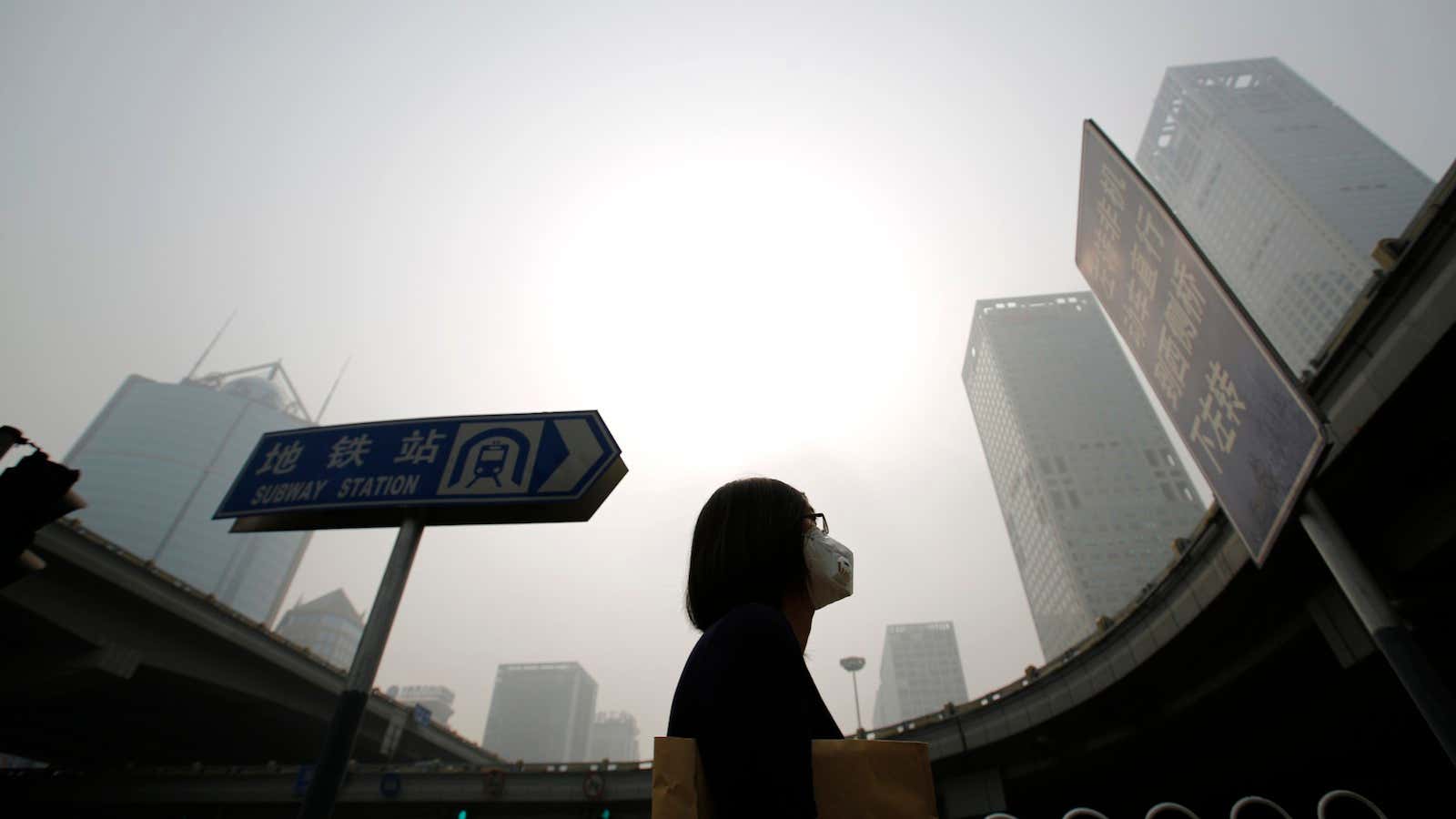

So I was fairly certain I had asthma. And while I was incredibly relieved to feel better, I was shocked and disturbed by my diagnosis. It’s not common at all for adults to suddenly get asthma, and of course my overwhelming thought was to blame it on air pollution. Finally, after eight years in Beijing, gasping through multiple airpocalypses, and despite all of my obsessive attempts to shield myself from air pollution, I believed the inevitable had caught up to me. I felt like a fool for ever thinking I could avoid pollution’s long-term health effects.

All of my blogging about masks and purifiers; my TEDx talk about healthy living in China; my book encouraging thriving health in China—all of it suddenly felt like sugar-coated wishful thinking, and my rose-tinted glasses finally shattered to reveal the truly ashen hues of my city’s “yellow fog”.

I felt trapped, helpless against the choking evil oozing invisibly and inexorably through window and door cracks, always finding a new hole after my frantically plugging another one. Anxiety filled my days, distracting me at work and home. I was no longer fully present with my family, my patients. I frantically retested all my air purifiers, added one in my office, and upgraded from N95 to N99 masks for my bike commute. Incense at our home during meditation suddenly devolved from a relaxing tool to an anxiety-provoking source of PM2.5. I even considered the previously unappealing but blindingly obvious “cure”: fleeing from China.

I didn’t take it very well, as you can see. “Disease produces much selfishness”, as Samuel Johnson once said. “A man in pain is looking after ease.” I even wrote a long blog article about my new illness and its profound impact on my life here, chronicling my desperate attempts to shield myself from pollution. I felt a massive release of catharsis after finishing the final draft, satisfied that it perfectly captured my state. And then I held off publishing it so I could revise later.

Now, a few months later, I’m relieved I never published that article, because what was diagnosed as asthma is now completely gone, for many months already. And now I know that my symptoms may well have had nothing to do with China’s air pollution—it had all been an infection, the sort one likely could contract anywhere in the world.

A stunning turn of events led to this discovery. I actually had been feeling much better after a few weeks with my inhalers and steroids, but mid-February I started again to get wheezy, along with very strange and seemingly disconnected symptoms such as muscle aches and frequent headaches. Then the night aches came back, and on Chinese New Years Eve I woke up gasping for breath yet again, this time with fever and headache. So instead of preparing dumplings and watching the annual TV gala, my family spent much of the night with me in my hospital’s emergency room. There I was diagnosed with an atypical pneumonia and started on antibiotics. Seven days later, all of my symptoms were gone—including the symptoms of asthma. I haven’t touched an inhaler since then.

Antibiotics kill bacteria. So as this medicine completely cured not only my pneumonia but also my supposed asthma, it’s apparent now that I had been walking around for months with a bacterial infection in my lungs, causing all of my symptoms from the chest pains at night all the way up to the more traditional pneumonia symptoms at the end—including my wheezing and asthma.

Looking back, it certainly wasn’t an illogical assumption for me and my colleagues initially to blame air pollution, as my initial symptoms had none of the typical features of a pneumonia infection. And the evidence is quite strong that air pollution can worsen asthma—but there’s actually less clear proof that it can cause new asthma in an otherwise healthy person like myself.

Yes, many studies do show an increase in hospital admissions for pneumonia during pollution spikes, so perhaps from this indirect pathway, air pollution was still partly to blame for my illness—although last winter’s air pollution was in fact much better than previous winters.

As I now reflect on those rough months, I’m disturbed how I was far too ready to play the popular “blame China” game. It’s such an ingrained reflex for Beijingers, both foreign and local, to complain about our many environmental troubles. Scandalous stories are so common that we’re hard to shock and easy to believe the worst. So of course, it seemed totally natural to me, my colleagues and my friends to think that air pollution caused my suspected asthma. But we were wrong.

My unpublished article thus has transformed both in tone and intent. No longer a simplistic screed, it’s become a more nuanced debate on environmental risks versus epigenetic predestination. But more importantly, it has become—at least for me—a cautionary tale about a person’s unpredictable reactions to pain and illness and the vulnerabilities it exposes. During my most serious illnesses ever, I was anxious and needy, retreating into a shell of survival. I was desperately searching to find some meaning, some positive outcome to my unexpected sickness. Looking back, I am a bit disappointed in myself, for reacting so negatively to what was honestly a not-so-serious diagnosis, especially in comparison to so much of the suffering I see in my own patients in clinic. I found that my emotional reserves in the face of illness weren’t as deep as I had hoped.

But from this humbling, grounding experience I have found more than a few positive sprouts, and thus the entire ordeal has proven to be an unexpected blessing. I now have a deeper compassion for others with illness, and I understand how a person’s perception of their illness is perhaps even more important for a doctor to “heal” than the actual illness. I’m more aware than ever of the deep connections between mind and body, between physical and mental health, both intertwined and inseparable.

I also never want to be so unprepared again for pain and illness, and I continue to reflect how I can improve whatever inner strengths I may need in reserve, even on a spiritual level. As New York Times columnist David Brooks says in his new book, The Road to Character, suffering “drags you deeper into yourself.” And as I now again revel in the pure joy of my wife and playing along with our two miraculous sons, I am filled with gratitude at everyone’s good health, now knowing how fleeting that can last.