Until China stamps out corruption, its debt habit will keep getting worse

Once again, the Chinese government is planning to kickstart its economy with infrastructure projects, a source of growth that it’s turned to off and on since 2008.

Once again, the Chinese government is planning to kickstart its economy with infrastructure projects, a source of growth that it’s turned to off and on since 2008.

The funding for this will inevitably be debt—hardly surprising given that, as Quartz just wrote, the Beijing administration has ever-fewer sources of financing left. Whereas China used to be the world’s workshop, now foreign investment in factories is falling as manufacturers turn to places such as Vietnam for cheaper labor. Meanwhile, the nation lacks the hearty consumer spending enjoyed by the US, Brazil and even Indonesia.

As Nomura analyst Zhang Zhiwei told Bloomberg, China’s economic recovery is “being driven mostly by monetary and fiscal easing.” So while China’s recent headline economic data has looked good—and, with the new stimulus measures, is set to look better still—the economy is running on artificial stimulants.

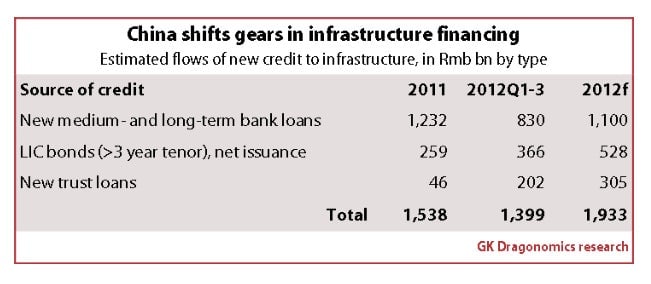

As this graph shows, China’s credit—from banks, corporate bonds, and even unsuspecting Chinese savers—is driving China’s infrastructure boom. In the last nine months of 2012, China pumped some 534 billion yuan ($85 billion) of debt funding towards infrastructure. And that was before this latest stimulus has even started.

Why does China refuse to try other economic models? It’s not for want of imagination. The central government has been trying to think of ways to rebalance away from debt-fueled state investment and towards domestic consumption for at least a decade. But as well regarded commentator Minxei Pei notes, it’s not just the government that is failing to adapt—the entire country is struggling as well.

That’s because, while developed economies such as the US benefit from domestic businesses giving money to each other, China has still not developed that sort of financial supply chain. Worse still, Chinese companies simply do not trust each other. Both of these come down to the “high difficulty of doing business in China,” Pei says, which are due to rampant corruption, the weak rule of law and poor property rights.

To make money then, Pei writes, Chinese private enterprises have largely become exporters—selling their goods to people they can trust. In other words, they would rather do business with Walmart or Target because they “do not have to worry about getting paid.”

It is this problem that made China’s economy so dependent on overseas exports for growth. But with global manufacturers now turning to cheaper countries, China has little choice but to fund the resulting shortfall in capital by directing municipal governments to borrow cash and build new roads and bridges. Such projects require a lot of workers, and keep people employed, fed and unlikely to try to overthrow the government. But as much as the government might wish to ignore it, the debt must at some point be paid.