Michael Kasper thought he was ahead of the game when he sat down to do his taxes this year. It was a Friday in February, more than two months before the mid-April filing deadline, and snow still covered the front lawn of his home in Poughkeepsie, in upstate New York. “I had all the papers,” he recalled. “I had the W2 and the 1099s stacked up, and I typed them all in.”

But a few hours after he tried to submit his tax return online, he got an email saying it had already been filed—a week earlier.

The story of Kasper’s tax return would eventually turn out to involve a bank account in rural Pennsylvania, a go-between on Craigslist, and a Western Union wire transfer to Nigeria. He was almost certainly one of the more than 330,000 Americans who fell victim to an audacious hack of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which was disclosed earlier this year. And the hackers didn’t use sophisticated malware or social engineering tactics—the hallmarks of many recent data breaches. Instead, they walked in through the front door of the IRS website, pretending to be regular people filing their taxes, and walked out with millions of dollars in fraudulent refunds.

The IRS has divulged few details about the data breach, but thanks to some amateur sleuthing by Kasper, who is a software engineer with a specialty in computer security, we’re able to fill in some of the blanks.

Protecting taxpayers from themselves

The Monday after trying to file his tax return, Kasper called the IRS’s identity theft hotline. As he would later tell a Senate committee hearing (pdf) on the breach, the operator he spoke to agreed that this looked like a case of fraud. Someone had filed a tax return under his name, presumably in order to intercept his tax rebate. And whoever it was, their plan was working: The IRS was due to send out the rebate that very same day, and it was too late to stop it.

Kasper asked for more details. Perhaps the bank account number listed on the fraudulent return would lead him to the thief, or at least confirm that it was a scam.

But the operator wouldn’t tell him. To comply with a law protecting confidentiality, the IRS doesn’t divulge the details of a fraud to anyone—including the taxpayer affected by it—until it has conducted its own internal investigation. A fraudulent return could include the personal information of another innocent taxpayer, John Koskinen, the IRS commissioner, explained at the Senate hearing (video, at 1:40:40). In fact, the IRS will leave not only the person affected by the fraud in the dark, but also law enforcement agencies and any banks where fraudulent funds have been sent.

Fighting bureaucracy with bureaucracy

Kasper felt this concern for privacy was protecting the criminals who had stolen his identity. Frustrated, he went to the “Get Transcript” service on the IRS website, which allows taxpayers to retrieve the details of their past tax returns. He figured it might lead him to the crook. But when Kasper attempted to use the service, he found that another email address was already registered to his Social Security number. He called the IRS again. Once more, though the people he spoke to seemed to agree that the address was fraudulent, they wouldn’t, for privacy reasons, tell him what the email address was.

But Kasper found a way to bypass the IRS’s stringent privacy rules with a little bit of bureaucracy—and a check. For $50, he was able to request a paper copy of his 2014 tax return, sent to his home address, which the scammers had not tried to change. By mid-March he had the fraudulent document in his hands.

This form, which had been filled out by strangers and submitted under Kasper’s name, looked very much like the return he himself had filed for the 2013 tax year. The crooks somehow knew Kasper’s Social Security number, his date of birth, and his real address. They knew his marital status. They even knew his salary. It was all right there on the photocopied form.

The only major differences between the 2014 return and the one Kasper had filed a year earlier were an additional $6,000 added to his withholdings—and a bank account number he’d never seen before.

How it happened

Not until May 26 did the IRS announce a major data breach. Hackers had used the “Get Transcript” page to steal data—specifically, the contents of previously-filed tax returns—on thousands of taxpayers, and then used that information to file the new, falsified returns. At first, the IRS said more than 100,000 people’s records had been stolen. This month it revised the figure up to 334,000.

Logging in to ”Get Transcript” is a two-step process that requires a lot of personal data. In the first step, a user has to provide a Social Security number, date of birth, tax filing status, and street address, according to the IRS statement. The second step is a common identity-verification method known as Knowledge-Based Authentication, or KBA, and it involves a series of multiple-choice questions that ask the user about his or her credit history. These questions can range from “On which of the following streets have you lived?” to “What is your total scheduled monthly mortgage payment?”

How had the intruders obtained all that data for 334,000 people? Names, addresses, and Social Security numbers could very well have come from previous high-profile data breaches, such as those at the health insurers Anthem and Premera Blue Cross. Indeed, Kasper was one of millions of Anthem customers whose personal data had been compromised. Personal data and identities from such breaches are also frequently sold on the “dark web.” But to break through KBA without also having credit information on hand—data that came from a bank or a credit bureau—would be difficult.

Difficult, but not impossible, Kevin Fu, a computer science professor at the University of Michigan, told Quartz.

“Just knowing a person’s address, which you can get from one of these more traditional breaches, you can discover a lot about a person,” Fu said. “For instance, you can make a pretty good guess on who owns their mortgage when [the KBA tests] present you with four banks and only one of them happens to be in the city that person lives in.”

All the same, while that approach makes sense for the thief who is looking to defraud only a handful of taxpayers and can manually answer KBA questions, it wouldn’t be practical to do it 334,000 times. Such a criminal would have to, for example, write some computer code to find all of the banks near each taxpayer’s address, read the multiple-choice options of the bank question, cross-reference the two, and hope for a hit.

A clue to the method the attackers used is that although they successfully stole 334,000 people’s tax information, they tried to steal it for another 281,000, according to the IRS, and got foiled at the final verification step. That could indicate that the hackers had credit data on only some of their victims, or that they found a pattern in the multiple-choice KBA questions that they were able to correctly predict about half the time. (For example, the correct answer to a given KBA question can frequently be “none of the above.”)

In any case, once the hackers had successfully obtained taxpayers’ personal data, they now had to use it to create new tax returns. Comparing Kasper’s real return to the fraudulent one submitted under his name, it seems clear that this process—which involves filling out PDF forms and submitting them online—would have been automated too.

Finally, they would have submitted the fake tax returns to the IRS, then waited. If a taxpayer had already filed a return when the fraudulent one was submitted, the fraudulent one would be rejected. If accepted, it would still have to pass a series of fraud-detection filters. When the IRS first announced the data breach in May, it said that 15,000 of the falsified documents got all the way through, leading to $50 million in refunds. Whether that number will rise after the IRS’s extended analysis is still under review, according to the agency.

But how did the criminals then collect the $50 million? In January of this year, the IRS started limiting how many separate tax rebates could be direct-deposited in the same bank account. To get around the limit, the hackers would have had to open thousands of bank accounts. There doesn’t seem to be a reasonable way for even a sophisticated criminal to do something like that. This part of the operation remains unclear; we still do not know how the crooks got paid.

In the case of Michael Kasper, however, we do know where the money went. Sort of.

The Nigerian connection

Back in March, Kasper looked over the fraudulent tax return that had been filed under his name. There was a bank account number on it that was not his, and next to it, a routing number. Kasper found out that the routing number belonged to a bank in Williamsport, a city of about 30,000 in central Pennsylvania.

After a few phone calls, Kasper reached Barbara Austin, the head of account security at the First National Bank of Pennsylvania. She told him that in February the IRS had deposited $8,936, with Kasper’s name and Social Security number as a reference, into an account in someone else’s name. Most of that money, Austin said, was now gone. And although Kasper had filed a fraud report with the IRS more than a month earlier, no one from the government had contacted Austin about the deposit.

Kasper then contacted the Williamsport police. Within a couple of days, a detective named Donald Mayes had checked with the bank and identified the owner of the account. Her name was Isha Sesay—a small-framed, 21-year-old resident of Williamsport.

Sesay told Mayes (according to an arrest warrant that would later be filed, and an email Mayes later sent to Kasper) that she’d been hired on Craigslist as a personal assistant. Her only duties were to open a bank account, into which funds would sporadically be deposited, and to wire some of those funds to places like Nigeria.

For her trouble, Sesay would be allowed to keep a portion of the deposits. She admitted to Mayes that the job seemed “odd,” but explained that she needed the money. Bank records obtained by the police indicated that Sesay had indeed written a check for $7,000 to cash, but she could not provide any documentation of the wire transfers she claimed to have made with that cash.

Sesay’s bank records also indicated that she used the leftover $1,936 for rent and daily living expenses. “By the end of February 2015,” Mayes wrote in the arrest warrant, “Sesay’s account would have a balance of $4.58.” The account was then closed.

A woman who answered a call from Quartz in early July at the phone number listed on Sesay’s arrest warrant made only one brief comment before hanging up. “Isha is dead,” she said.

Mayes told Quartz Sesay is still living, as far as he knows. She waived her right to a preliminary trial, Mayes said, and was released on $8,500 bail. He added: “She’ll end up taking a plea and probably won’t go to trial.” In addition to the fraudulent tax refund, police found that Sesay had also received a deposit linked to a romance scam. She is charged with receiving stolen property.

It seems most likely that Sesay was merely a small part of a much larger operation. In his email to Kasper, Mayes noted: “You still have to contend with the fact that she may be telling the truth and that someone else has obtained your personal information.”

Dubious solutions

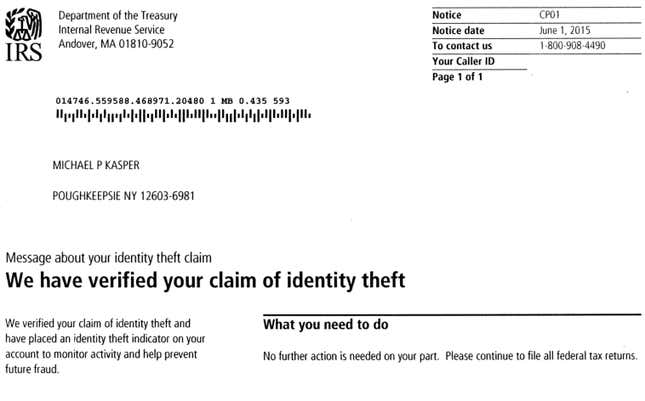

Michael Kasper received his actual tax refund on May 12, along with a letter confirming that this was a case of identity theft. “But I don’t know if they ever tried to prosecute anyone,” he said, “or identified whether it was from overseas or what.” And the IRS was not interested in what Kasper had found out about his case.

“I even tried to call them back and say, look, somebody’s been arrested, here’s some additional information,” he said. “And they literally would not take that information when I called. They said, ‘We do not accept tips on identity theft.’”

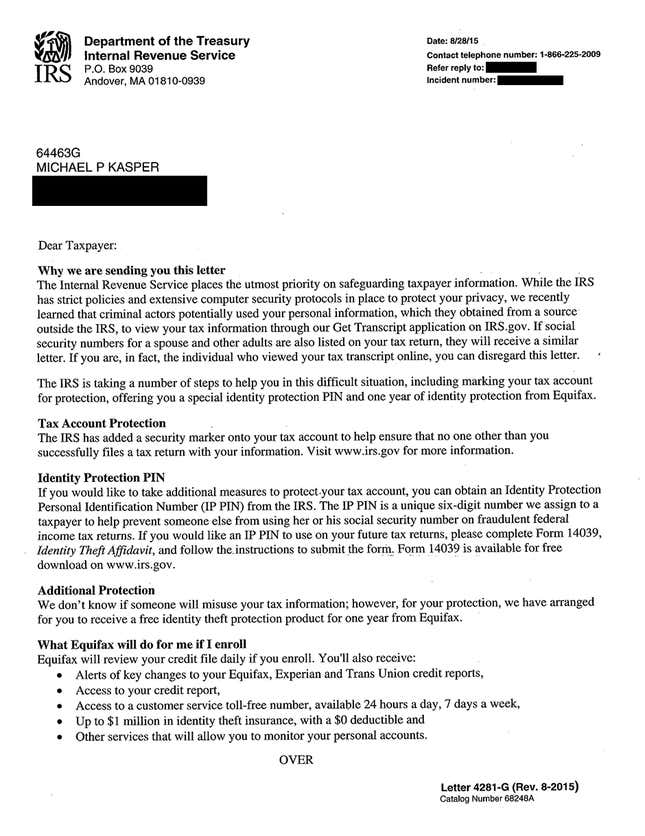

The IRS has yet to confirm or deny whether the fraud committed against Kasper was part of the larger scam. However, like the 334,000 victims of that scam, Kasper has received a special “Identity Protection PIN” from the IRS, which he will have to use to confirm his identity on future federal tax returns. He argues it’s not a secure solution.

“I already know that whoever got my tax transcript can also get my identity PIN the same way,” he said. “They have the same authentication on the website to get the identity PIN as they do for the ‘Get Transcript.’ So I don’t know what’s going to stop someone from filing again as me next year.” Fu, who has gone through the login process for retrieving an IP PIN, told Quartz the process is indeed similar, and possibly even slightly less secure.

The IRS did not comment on that, but did send Quartz a statement outlining the security benefits of IP PINs. For one, it said, access to an IP PIN itself “does not expose taxpayer Personally Identifiable Information.” (It doesn’t grant access to other personal data, in other words.) Also, taxpayers who use IP PINs will be sent a new one in the mail each year, “prior to each tax season—making it much harder for an identity thief to access this information.” That is, hackers would have a small window—between the end of the tax year and the moment a taxpayer files a return—to try to steal the IP PIN. The statement added: “In addition, we carefully monitor IP PIN traffic in order to respond swiftly to any potentially suspicious activity.”

The IRS commissioner, John Koskinen, suggested at June’s Senate hearing that the agency will bring back the “Get Transcript” page with stronger authentication, but did not say whether KBA will be reviewed across the board. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report in January, before the fraud was announced, had noted the limitations (pdf) of the KBA process.

Koskinen also said that, in cases where someone like Kasper needs a copy of a fraudulent document filed under his name, the IRS has set up “a situation where we can simply redact any third-party information on a return and give the taxpayer a copy of the fraudulent return so they’ll know exactly what was in there.”

Kasper suspects that means the IRS would remove the only information that led him to Williamsport, and that helped the police there find Isha Sesay. “It would not surprise me at all if they do that,” he said.

Left behind

For the IRS, the fraud problem far exceeds the $50 million lost in this one incident. According to the GAO’s January report, the IRS prevented the loss of $24.4 billion to fraud in 2013, but still lost a total of $5.8 billion that year. And although the agency currently has 81,000 full-time employees and an operating budget of $10.9 billion, it initiated only 4,297 criminal investigations in 2014—some 1,000 fewer than the previous year. Meanwhile, the number of sophisticated computer attacks nationwide continues to rise.

At the hearing, Koskinen listed several reasons the agency is not excelling in the realm of computer security. Its systems are antiquated, he said. Some of its applications “have been running for 50 years.” Some of the software used at the IRS is no longer supported by the people who made it. And the agency simply doesn’t have the funds in place, he said, to recruit top talent from the private sector.

He added: “It’s a difficult challenge competing with organized criminals who have resources.”

As of mid-August, the IRS still had not contacted the First National Bank in Williamsport, nor the police there who solved Kasper’s case.

Update, September 4, 2015: Michael Kasper received confirmation from the IRS that the fraud committed against him was part of the larger data breach. Here is the letter he received: