MANDALAY— This weekend, Myanmar is hosting a BarCamp, a technology “unconference” where entrepreneurs, technologists and political activists gather to swap ideas. Remarkably for a country where military rule ended only in 2011 and economic reforms are only just getting going, this is its fourth BarCamp, and last year’s broke the record for the world’s biggest BarCamp ever, with 5,000 attendees.

But this year’s takes place among some big changes in the environment for technology entrepreneurs. In November the country passed a new foreign investment law, though corruption and cronyism remain rife. A bill is in the works to bring Myanmar’s ancient telecommunications legislation up to date, though critics want provisions that would severely cramp civil liberties to be removed. This week, the government announced that it would grant two telecoms licenses to local or foreign companies, and set a Jan. 25 deadline for expressions of interest.

And meanwhile, foreign firms are taking tentative steps. On Jan. 14, Taiwanese phone-maker HTC—whose CEO, Peter Chou, revealed only last year that he was born in Burma—released six smartphones specially made for the Myanmar market with a Burmese-language keyboard and operating system, the first to do so.

But that doesn’t mean things are straightforward. HTC’s new phones use the Android operating system, but the Google Play store, the main channel for downloading apps, isn’t available yet in Myanmar. (A Google spokesman said the firm has “nothing to announce at this time” about a launch.) Another option, the Amazon App store, requires a Mastercard or Visa debit or credit card—but these card networks have only just started making licensing deals to local banks.

A well-known Burmese entrepreneur, who asked not to be named, says he tried to create a central online app store from which Burmese could legally download apps. A government ministry, however, claimed to “license” who can vend apps online, and has denied his and other requests. As a result, and also because of slow internet speeds, Burmese have to buy their apps in person at mobile-phone stores. Another popular option is to pirate them from Myanmarmobileapp.com and other websites.

A second problem is price. With phones starting at 250,000 kyats (about $285) and SIM cards at 200,000 kyats, they are well out of reach of most Burmese, where the average salary in 2010 was $27 a month. That said, SIM prices are changing, albeit in the midst of confusion. They were supposed to drop to 100,000 kyats starting Jan. 4, until the plan was cancelled after a few had been sold. The telecoms minister resigned this week, reportedly over a dispute about the price of SIMs (he wanted it to be higher).

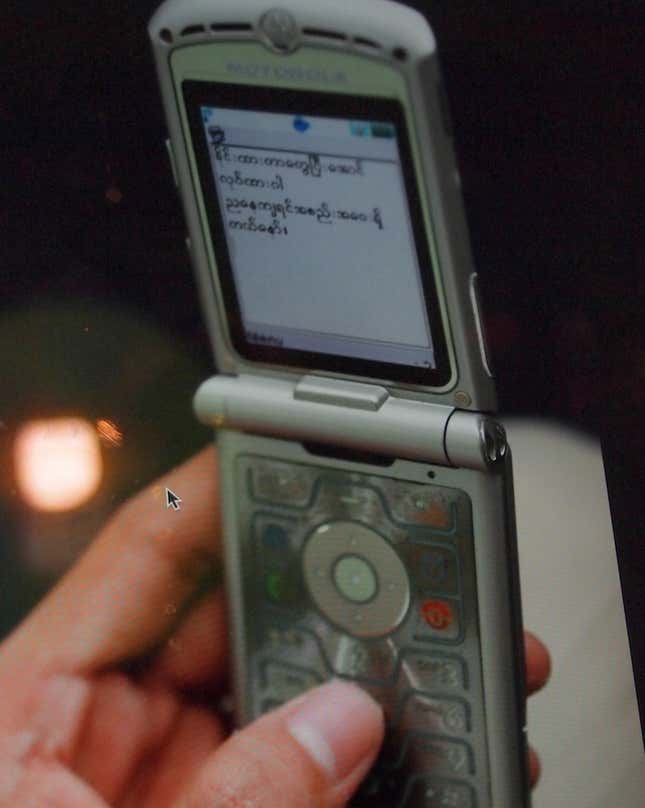

In the meantime, though, numerous Burmese-language apps, keyboards and browsers come pre-installed on jail-broken phones, available on every corner of downtown Yangon’s streets. What may be Myanmar’s “first ever app” added Burmese-language support many years ago (see below). It will be a while before most Burmese graduate from these home-grown solutions.