Today, Verizon reported a $4.23 billion loss in its fourth quarter, due mostly to its costly pensions and benefits scheme. A shortfall in its pension fund also prompted AT&T last week to warn that it will take a $10 billion charge in its fourth quarter earnings, which it announces on Jan. 24—a sizeable setback against its expected $32.2 billion in fourth-quarter sales.

These companies aren’t alone. The collective shortfall for corporate pension plans is massive. In a white paper in August, Goldman Sachs pension strategist Michael Moran wrote (emphasis mine):

S&P 500 companies had almost $440 billion of unrecognized losses on their US [defined benefit] plans at the end of last year. That figure is even greater when unrecognized losses from non-US [defined benefit] plans and retiree health care plans are included. Much of these losses have been generated in recent years from gross pension obligations rising due to falling interest rates.

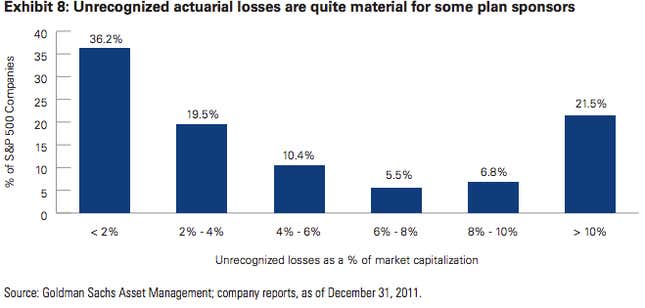

Nor are AT&T’s and Verizon’s pension holes the biggest. For example, a year ago, when the data in the chart below were calculated, AT&T had a market capitalization of $177.5 billion (today that number is $189.4 billion). Although we don’t know the size of unrecognized losses the company harbored at that time, if they were the same as the charges it announced last week, they would have amounted to about 5.6% of AT&T’s market capitalization. Quite a few companies were in worse shape then—and though they made money in 2012, $440 billion would be a big number to overcome.

So, why this shortfall? Some of it can be blamed on the low interest rates that have been prevailing since the financial crisis. The present value of a pension fund—the amount of money it needs to contain now to pay out pensions that will be due in the future—is calculated essentially by adding up those future liabilities and applying a “discount rate” that reflects how fast the money now in the fund will grow as it’s invested. The discount rate is tied to interest rates. When interest rates go down, so does the discount, and the present value goes up, leaving the fund with a hole to fill.

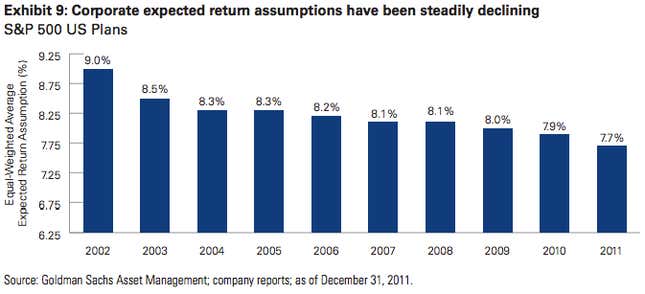

As a result of the low-interest-rate climate, pension funds, just like other investors, have had to move into increasingly risky assets to get the same kinds of returns as before. This would make sense but for two problems: First, pension companies in general tend to project unrealistic returns, and second, they often don’t properly account for the risk.

AT&T, like many of its peers, has now cut back its discount rate for today’s low-yield market, from 8.25% to 7.75%. However, Allison Schrager, an economist and pension fund expert, scoffs at the change: “Even that, with the interest rates we’re seeing right now, is unrealistic”; it’s difficult for funds to actually make that much money off their investments.

Still, Schrager qualifies, returns aren’t the real issue. “Their investments aren’t so much of a problem as the fact that they underfund their plans to begin with,” she says. Corporates are notorious for using unrealistically rosy expectations across the board. They poorly account for the money they should be adding to their funds each year, and the fund can end up in trouble when going after risky investments to get close to that return. “Whenever I work with these DB [defined-benefit] plans I always think… they don’t really understand how risk works.”

Verizon and AT&T are healthy companies, however, and with the multi-billion-dollar charges (essentially, diverting cash to funding their pension programs) they have shored up their pension programs against failure—at least for now. The tab for pensions offered by companies that go bankrupt—and even some that don’t—is often paid by the American taxpayer through the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

But expect to see other companies take massive charges for failing to properly manage their pension funds. According to Schrager, any corporation with a DB plan could be at risk.