On July 13, Hillary Clinton took aim at one of the most baffling economic problems of our times: how to raise incomes for hard-working Americans so they can afford a middle-class life.

Clinton did not say exactly how she would solve this problem, although spurring growth and jobs, improving training and investment in infrastructure certainly seem to be part of her solution.

She also proposed corporate profit-sharing schemes, and more traditional measures like overhauling the tax system to give relief to the middle class, strengthening trade unions and increasing collective bargaining, as well as reining in excessive risks taken on Wall Street and creating incentives for investments in infrastructure and research.

But while some of these proposals may help in the achievement of her main goal, some others may actually work against it. For now, Clinton’s economic program looks like a smorgasbord of measures hastily thrown together, rather than a carefully-considered strategy.

What she’s taking on

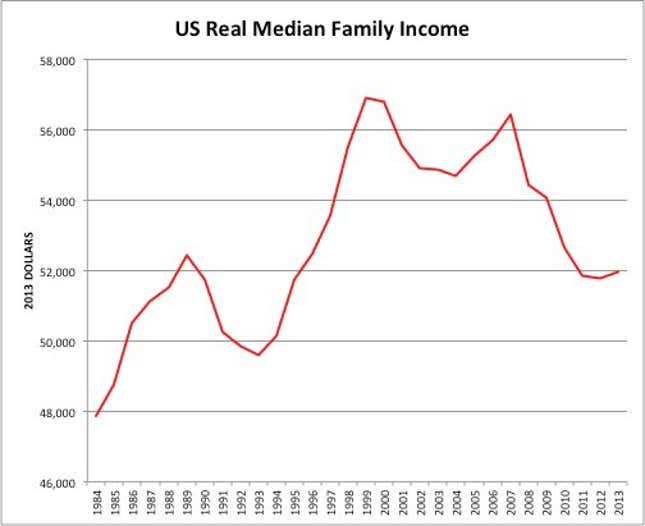

As shown in this graph, the median family income in the United States has been declining since 1999—with a brief exception in the boom years of 2004-2007—which then led to an even sharper decline.

Data: US Bureau of the Census

The decline in real incomes is affecting all families. The most affected ones, however, are those Clinton seems to be thinking about: the unskilled workers, who are in danger of losing their middle class status to become part of the poor.

Real wages have stagnated and even declined since the late 1970s, even though if you divide the US GDP per inhabitant, they should be making more money. And depressed wages have been associated with a long-term tendency of unemployment to increase. This tendency has been painfully felt in US family finances during the recovery from the Great Recession, as the unemployment rate has not declined proportionally with the recovery of production.

In June 2015, unemployment finally declined to 5.3%, a percentage that is considered “full employment” in the United States (even in full employment people between jobs represent about 5-6% of the labor force.) This decline, however, is largely the result of Americans dropping out of the labor force altogether. Indeed, the labor force, as shown in the next graph, is at its lowest level in the past ten years.

Data source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics

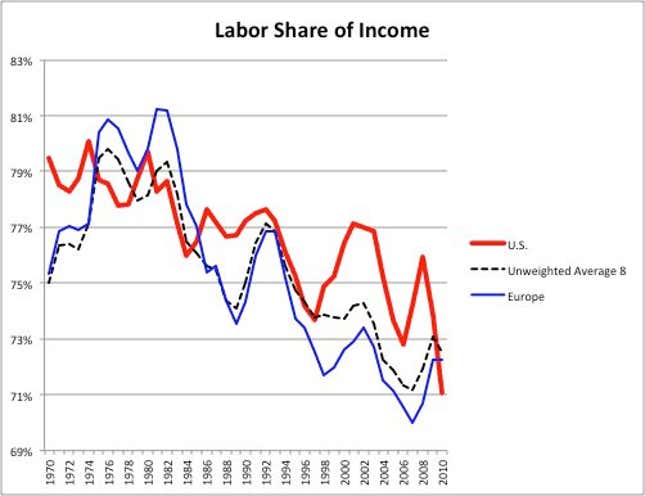

This next graph shows that workers’ share of total US income (the incomes of labor divided by the country’s total income) has declined substantially in the last several decades, from about 80% in 1970 to 71% in 2010.

This trend is not exclusive to the United States. The blue line shows that Europe has experienced the same trend, and the black dotted line represents the average of eight developed countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and several European countries. All countries show the same decline.

Data source: Piketty-Zucman 2013 (March 17, 2013)

Of course, if the share of labor is declining, the share of capital must be increasing since the sum of the two must be 100%. Firms are expanding production by investing in capital rather than hiring people. That is, they are increasing the ratio of capital to laborers. They have more machines per worker. So why are they doing this?

Probable causes

One explanation is that firms are adjusting to the digital revolution. This adjustment privileges capital over labor for three reasons.

First, the digital revolution is orienting investment into labor-saving capital goods. By multiplying the power of the mind these technologies increase the output per person, reducing the demand for labor. This effect is more negative among the least educated workers.

Second, to accommodate the new revolution, companies have to replace old machinery and equipment for the already existing personnel. This requires additional investment that does not increase the demand for labor.

Third, digitalization reduces the cost of the capital goods. Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman, both of the University of Chicago, estimated in a recent paper that the price of capital goods has declined by 25% in the last 35 years.

They attribute this reduction to the impact of the digital revolution on the production of capital goods. They further estimate that the additional investment elicited by this price reduction resulted in a 5% decline in the labor share in total income in a sample of 59 countries over the same period (because, with this new investment the amount of capital per worker increased, and the share of capital in total income increased by 5%.)

There is another dimension to the effects of the digital revolution on the demand for labor. By facilitating the coordination of complex tasks at a distance, the new technologies are globalizing the labor markets, increasing the supply of labor with millions of people living in developing countries.

In this way, for example, millions of Chinese farmers entered the global industrial market for unskilled labor in the last two decades, keeping the cost of that labor low and taking away many job positions from developed and other developing countries. Also as a result of the digital revolution, Indian clerks have been displacing clerks in the developed countries.

In addition to these structural causes, the Fed has been keeping interest rates at record low levels, thus artificially reducing the price of capital relative to that of labor. The central banks of all the developed countries are doing it. This would go a long way to explain why the share of capital in total income is increasing throughout the globe.

A problem bigger than the United States

There is no easy solution to any of the structural problems. The ones that suggest themselves in a simple minded way, like increasing the taxation of capital to fund transfers of money to the poorer classes, or increasing protection to close the economy to the growing globalization, would create more problems than those they would resolve, even for the unskilled workers.

The United States is a very successful exporter, and closing the domestic market would also close the access of American products to the rest of the world—even if the other countries do not retaliate. This would happen because the competitiveness of the United States would decline as a result of the inflated wages that would be the objective of protection.

The same can be said about other ways to force wage increases. Increasing collective bargaining sounds like turning to solutions of a distant past, when the factories, the people and the global economies were radically different. The only goods-producing workers that could extract rents from their labor without being crushed by competition from abroad are those in the construction sector. Today they represent just 3.9% of all wage and salary workers. Most others work in services, many of them in activities that cannot be easily framed into collective bargaining.

Profit sharing sounds more promising than it is. The market tends to adjust to the technologically driven distribution of income between labor and capital. If companies are forced to establish profit-sharing schemes, they will in time adjust the sum of salaries plus profit sharing to the marginal product of labor—or, said in other words, to what the wage would have been in the absence of profit sharing. In any case, it is difficult to believe that the sharing would be enough to change things substantially.

The problem is not easy to resolve on the side of the Fed, either. Even if she were elected president of the United States, Clinton would not have the power to manipulate the interest rates. And it is not easy to decide what to do with them. Increasing the interest rates, as the Fed is saying will do, would eliminate the artificial incentives to substitute capital for labor that exist today. Yet, it would tend to reduce investment in general, and growth with it.

What Clinton does not seem to have grasped is that this is a problem bigger than the United States.

It is affecting the entire world in probably uncontrollable ways. She cannot be thinking of stopping technological progress, which would be another suicidal way of dealing with the problem. The fundamental problem or her approach is that, except for her proposal of improving adult training, her proposals tend to protect workers against change rather than helping them to embrace it.

Forcing companies to pay higher wages to diligence drivers did not help them when the car had already been invented. Collective bargaining did not help railroad workers when these were shrinking under the competition of trucks and airplanes. Aggressive trade unions would only increase the appeal of laborsaving machinery.

The solution should aim at accelerating the integration of the American economy to the new, more horizontal global economy that is emerging from the digital revolution. The solution is not in trying to stop the arrival of this new economy, but in adjusting fast to it. This requires a totally new approach, less oriented to regulate and more oriented to foster the traditional creativity of the American society.

Thus, Clinton has targeted a crucial problem. This has merit. Her economic program would get an “A” in terms of the relevance of the problem she wants to resolve and its benefit to the American citizenry. However, it cannot be rated overall until she explains how is she going to do it. She still has to think deeper on the complexities of the problem she chose.