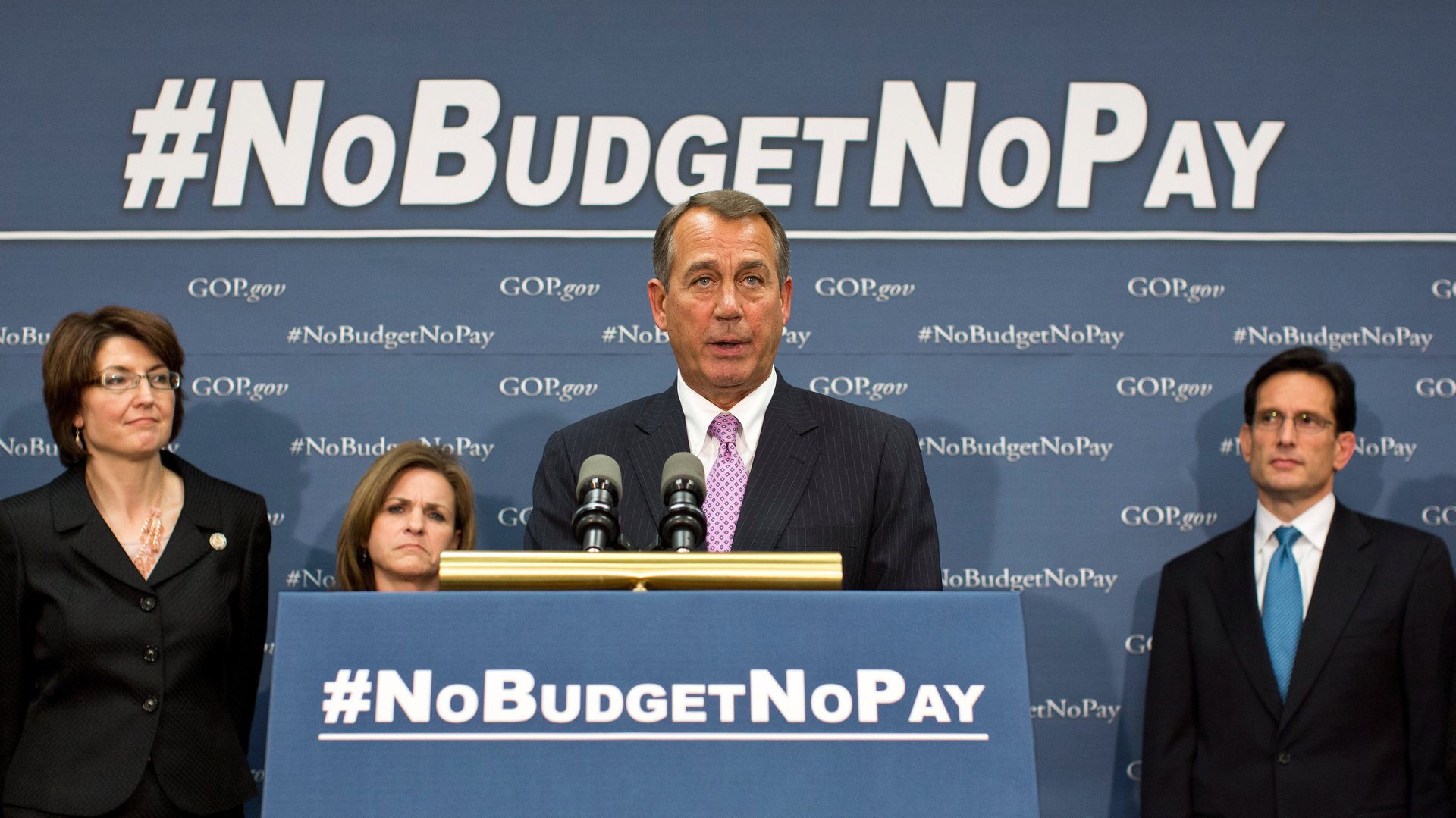

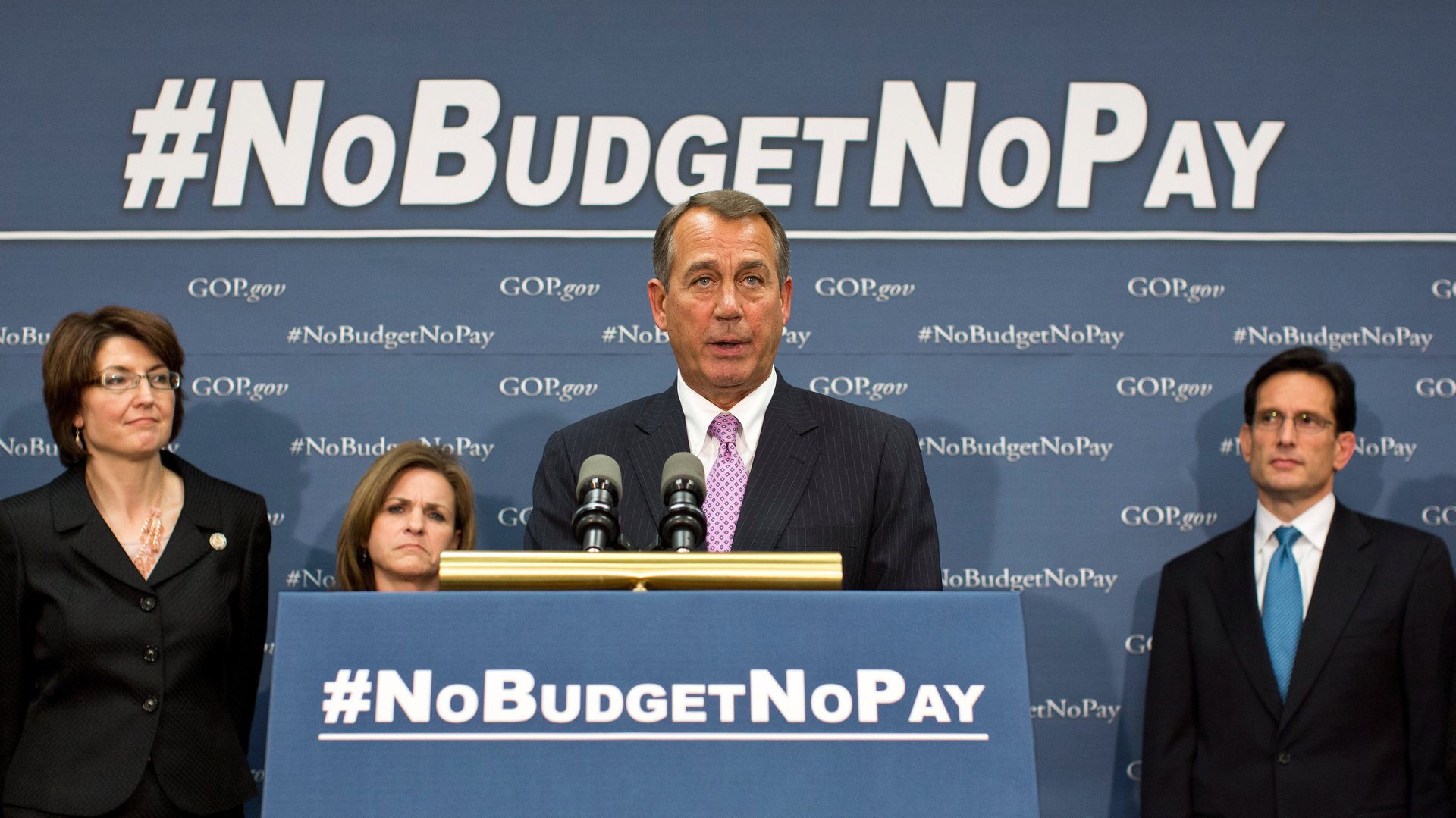

Republicans authorize $450 billion in new debt to avoid crisis and set up for a shutdown

The US debt ceiling will be lifted—a little bit. The House of Representatives today voted for a three-month extension to the country’s borrowing limit, which the President and the Senate are expected to confirm shortly. The increase, effectively lifting the limit by $450 billion, avoids the crazier fiscal scenarios and allows Congress to turn its focus to agreeing on a fiscal plan. The only little catch in the bill is that if both chambers don’t pass budgets by April 15, as Senate leaders promised to do today, it docks their pay.

The US debt ceiling will be lifted—a little bit. The House of Representatives today voted for a three-month extension to the country’s borrowing limit, which the President and the Senate are expected to confirm shortly. The increase, effectively lifting the limit by $450 billion, avoids the crazier fiscal scenarios and allows Congress to turn its focus to agreeing on a fiscal plan. The only little catch in the bill is that if both chambers don’t pass budgets by April 15, as Senate leaders promised to do today, it docks their pay.

The real challenge now will be the near-term deadline of March 27, when last year’s spending authority ends and the government shuts down.

Getting a fiscal agreement worked out won’t be easy. While the debt ceiling extension improves the Republican negotiating position by robbing the president of his ability to portray the GOP as totally reckless, the ugliness of a government shutdown isn’t much of an improvement. The same tactic in 1996 eventually produced a budget deal between a Democratic president and a conservative House of Representatives, but it didn’t paint Republicans in glory.

The Republicans who dominate the House still want more spending cuts, but Senate Democrats and the White House won’t enact them unless they’re balanced by tax increases. While the bulk of US fiscal consolidation so far has been through spending reductions, leading conservatives like House Budget Committee chairman Paul Ryan are still refusing to consider tax reform that lowers rates and raises revenue. And it will likely take Democratic votes to pass any such balanced package (as today’s debt ceiling vote did), because not all the House Republicans will sign on to one.

The problem now is that the speaker of the House, the Republicans’ John Boehner, has promised a budget that reaches balance in ten years. There’s no compelling reason to do this: While stabilizing the debt is a reasonable goal, it doesn’t require a balanced budget by 2023. When the Peterson Foundation commissioned five think tanks to come up with a debt-stabilization plan, only one, the conservative Heritage Foundation, did it by balancing the budget—and, because it refused to raise taxes, its plan required cutting domestic spending to levels not seen in over a half a century while completely restructuring politically popular programs like Medicare and Social Security.

Also hemming in Boehner is the party’s budget from last year, which wouldn’t have led to balance by 2023 but did dramatically cut both taxes and spending. Meeting the new goal will require the party to navigate a political minefield, as Josh Barro explains—how do you maintain your commitment to last year’s tax plan while also cutting an additional 1.2% of GDP from an already spartan budget? And after they do that, how will they reconcile it with a Senate document that will cut some spending overall, but also increase taxes and add new investments to spur the economy?

So though Congress bought itself more time today, there’s a good chance of more brinksmanship, leading to a potential government shutdown, before a deal is reached. Nonetheless, it’s out of the fire and back to the frying pan for the US fiscal debate.