They call him the “CEO monk,” and the nickname is well earned. Shi Yongxin serves as the abbot of Shaolin Temple, the famous kung fu sanctuary in central China with some 1,500 years of history. He’s sparked increasing controversy with his aggressive commercialization of the temple, and recently he’s fallen under official investigation for misbehavior. That, in turn, is leading to more scrutiny of his dealings in business and politics.

Shi stands accused of embezzling temple funds and having sexual relations with at least two women, and fathering children along the way. The religious affairs bureau of Dengfeng, the city that encompasses the temple, says it’s been asked (link in Chinese) by national authorities to investigate claims against Shi recently made online by an anonymous poster.

The accuser, purportedly a former monk, published a post entitled ”Who is to inspect this big tiger, the abbot of Shaolin Temple?” and has been slowly giving the Chinese media revealing (and yet-to-be-verified) documents.

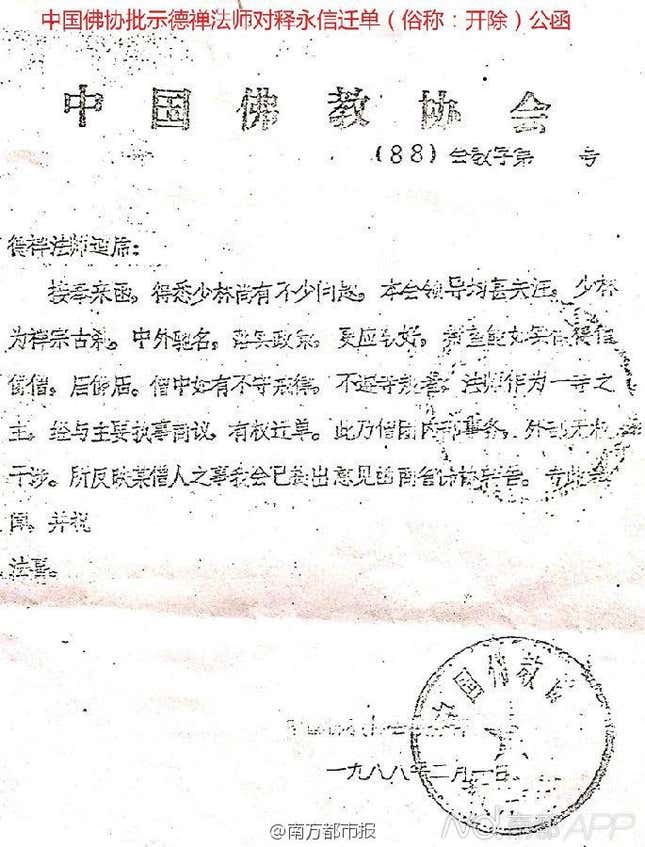

One of them (link in Chinese) dates back to the late 1980s and allegedly shows Shi being kicked out of Shaolin Temple because of theft and other accusations from his master. A birth certificate (link in Chinese), along with photos of a mother carrying a child in her arms, seems to indicate Shi has an illegitimate child with a mistress, who the accuser said has received money from temple-related business.

Attempts by Quartz to call the Shaolin Temple liaison office were unsuccessful. But the organization posted a statement (link in Chinese) on its website saying these claims are rumors fabricated by people intending to harm Zen Buddhism. It also said the temple has contacted legal authorities to bring a libel case.

Shi’s business savvy has been evident since he became the temple’s abbot in 1999. He’s boosted Shaolin’s international profile and generated significant income for the organization. He’s rented the temple out for films, reality TV shows, and kung fu performances. The temple has an online store, where a copy of the Shaolin kung fu manual went for nearly 10,000 yuan ($1,600).

Shaolin Intangible Assets Management Co., established in 1988, protects the temple’s brands and intellectual property, and has registered over 200 trademarks in 45 categories. The temple itself owns 10% of the company’s shares. Shi owns 80%, according to the National Company Credit Information System.

The temple has nine other affiliates—most founded during Shi’s tenure—involved in various activities, including cultural exchanges, martial arts performances, a pharmacy, and publishing. One, Shaolin State of Joy Co., is also a registered subsidiary of Shaolin Intangible Assets Management Co. A certain Han Mingjun owns 35% of the company’s shares (link in Chinese). In the online accusations leveled against Shi, Han Mingqun is also the name of an alleged mistress.

Shi has aggressively leveraged the temple’s brand overseas. He’s chairman of the Shaolin European Association, founded in Vienna in 2010. Shaolin temples can be found in the England, Germany, and the US. And in Australia, Shi and company will build a $297 million, 500-bed hotel complex, including a temple, live-in kung fu academy, and 27-hole golf course.

In recent years Shi has also been a delegate of the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislature, making him a semi-politician. During the NPC meeting in March, he was seen showing other delegates his iPhone 6 Plus (link in Chinese). But during a group discussion held in the presence of media, he skipped out early.

This year, he brought up a proposal (link in Chinese) to correct online language that shows disrespect to Buddhism, as he thinks monks or nuns should never be called “Mr.” or—pointedly for him—“CEO.”