Puerto Rico defaulted. And no one should be surprised.

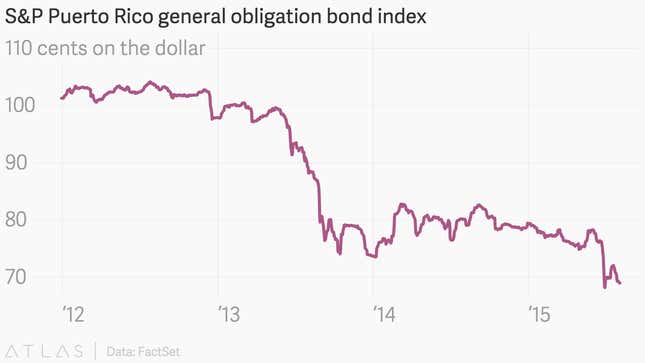

Ratings agencies and bond markets have been screaming about the risks for, literally, years.

No, the surprising thing is that the economically troubled Caribbean island was able to rack up debts of more than $70 billion—and who they were able to borrow from.

Puerto Rico’s downturn has been a decade in the making. The country has essentially been in recession since 2006, when section 936 of the US tax code was fully phased out.

The provision had exempted some US companies operating in Puerto Rico from paying taxes on their profits. (Various versions of the law had been in effect since the 1950s, and were crucial to stimulating the island’s economy.)

The already slowing manufacturing economy—once a miracle of the region—turned sharply lower. The economic decline produced a slump in tax revenues, which were no longer sufficient to pay for Puerto Rico’s bloated public sector. Deficits exploded higher.

“They were always hoping that recovery was going to happen next year,” says Tim Blake, managing director at the public finance group at Moody’s Investors Service. “Next year never came. The recession just kept growing.”

Over time, Puerto Rico’s debt burden ballooned to ludicrous levels that should have dissuaded anyone with a modicum of sense from buying them. For example, by 2014, Puerto Rico had approximately as much debt outstanding—roughly $61 billion worth of rated bonds, by Moody’s count—as New York state. New York’s debt-to-state GDP ratio, a gauge of the ability to pay, was a slightly high 4.7% that year. Puerto Rico’s was a nonsensical 53.9%.

So who was buying these ridiculous securities? Rich people. Affluent individuals dominate the market for municipal bonds. And the US municipal bond market loved Puerto Rican bonds. Why? Because money, as the millennials like to say.

The debts of Puerto Rico have been exempt from US federal, state, and local taxation since 1917. Normally, US municipal bond investors can only take advantage of municipal bond tax exemptions for bonds issued by the states in which they reside. So, for instance, a New York muni bond investor would have to buy New York state bonds. Puerto Rico’s triple-tax-exemption incentivized investors from all over the country to buy the commonwealth’s debt.

In addition to that incentive, Puerto Rican bonds have paid quite high yields in recent years, a reflection of the territory’s large debt burden and the risks it entails. The prospect of lower taxes and higher returns ensured healthy demand for Puerto Rican bonds.

“In the past, Puerto Rico bonds were among the most popular holdings for municipal investors,” wrote analysts with Fitch Ratings.

The result: Roughly half of all US open-end municipal bond funds own some form of Puerto Rican debt, Morningstar says.

What’s the lesson? Well, we’ve seen this story over and over again. When Greece was admitted to the euro zone, investors clamored to lend the country money. The rush pushed the prices of Greek bonds sharply higher, and the country’s borrowing costs—which move in the opposite direction of bond prices—fell sharply. Similarly, during the years before the recent US recession, investors all over the world raced to buy the packages of shady housing loans that Wall Street had become so good at constructing. Demand for tax free investments allowed Puerto Rico to tap a seemingly never ending pool of capital.

And the end result is always the same. Borrowers end up in over their heads and with little hope of paying back the debts. Perhaps it was foolish for the Greeks, the Puerto Ricans, and low-credit Americans to accept the cheap money from the markets. But it wasn’t any less foolish for investors to offer it.