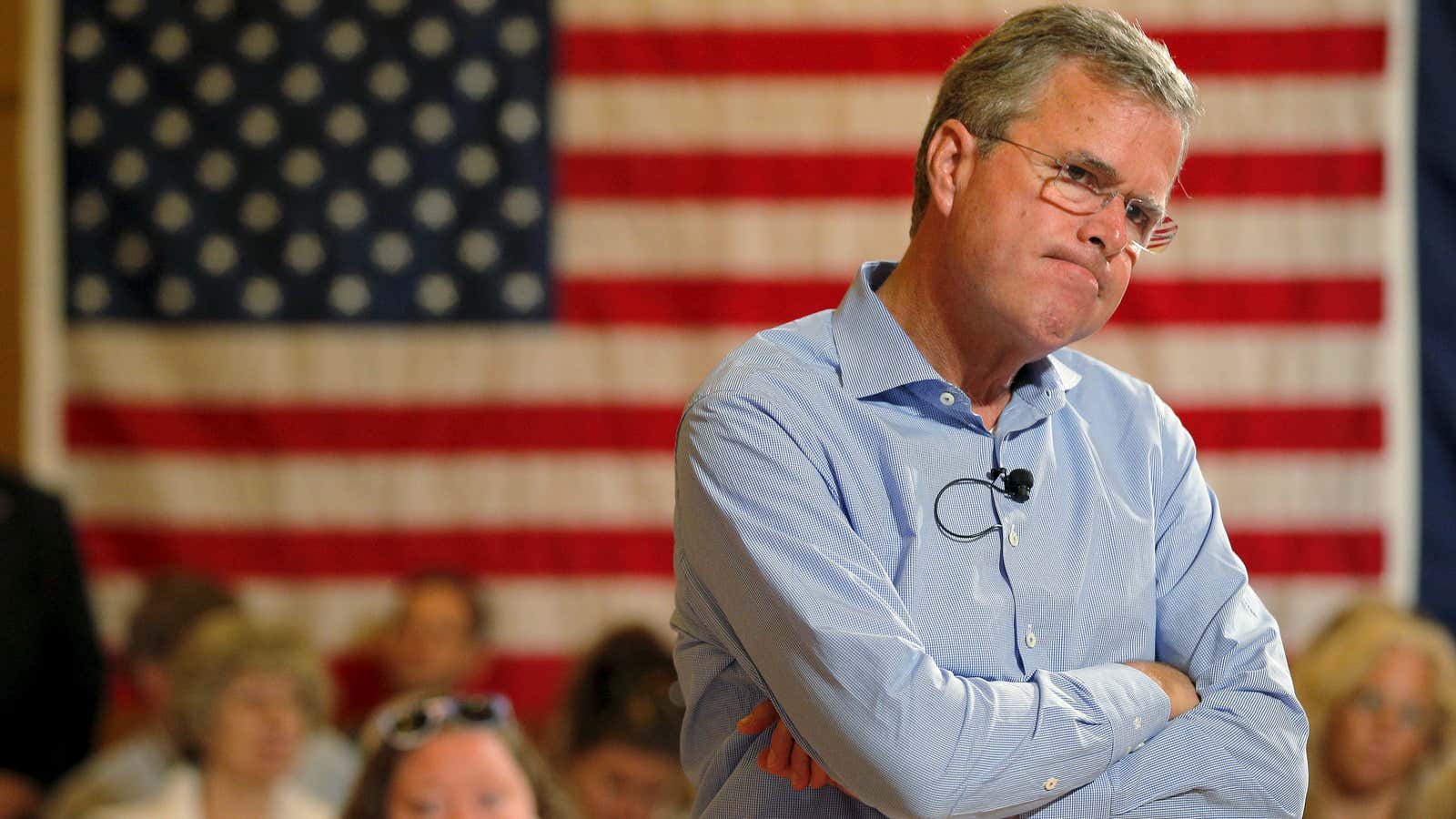

Jeb Bush’s presidential campaign has raised just $11 million for political activities—not much more than socialist senator Bernie Sanders’ $8 million fundraising haul. But Bush is still a leader in the race for political cash. That’s because Right to Rise, a “Super PAC” closely allied with his campaign, has picked up more than $100 million this year.

Right to Rise can spend that money on advertisements, field workers, and anything else to bolster Bush’s election prospects—just so long as it doesn’t communicate directly with his main campaign. More and more political activity on both sides of the aisle is moving to these committees, which operate under laxer spending and disclosure rules than campaigns themselves.

One of most intriguing donors to Right to Rise is the US Sugar Corporation Charitable Trust, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit that gave $505,000 to the Super PAC over the first half of this year. Or so it seemed when those records were released six days ago—now, Right to Rise says that the money came from the US Sugar Corporation itself.

“Since our filing on Friday, the report has been amended to accurately reflect that the contribution came from the U.S. Sugar Corporation,” Paul Lindsay, a spokesperson for Right to Rise, told Quartz in an e-mail.

It’s not clear how the filing came to be. Lindsay said it was ”just an administrative error” at the committee, and the US Sugar Corporation has yet to reply to requests for comment. But it’s clear why changing it was important: Campaign finance experts say that donations from a charity to a political committee would likely violate US tax law.

Charities don’t typically get involved in political campaigns; in fact, they’re forbidden to do so, or else they lose their tax-exempt status, which is a key incentive they use to attract funding. Trustees of 501(c)(3) nonprofits must attest each year that their foundation did not ”attempt to influence any national, state, or local legislation or…participate or intervene in any political campaign.”

The US Sugar Corporation is a major force in Florida, where Bush was governor from 1999 to 2007. It is one of the largest US sugar cane producers. It also produces 100 million gallons of orange juice in a season and runs a regional railroad to move it all. Like any company, it advocates for its political interests. (Australian trade minister Andrew Robb blamed swarming sugar lobbyists for throwing a wrench into negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which stalled out at a summit meeting just last week.)

But a charity donating to a Super PAC?

“I’ve never seen that before,” says Ian Vandewalker, a campaign finance lawyer at New York University’s Brennan Center. “The rule is you can’t do political activity.”

If the donation had come from the charity, then the question, he says, is how regulators define political activity.

“IRS people will take a look at the activity and weigh all the facts and circumstances and past history of this group and say, ‘Do we feel like this is political activity at all?'” Vandewalker says. “That said, giving money to a Super PAC that, according to press reports, is devoted to electing Jeb Bush president, it’s hard to imagine what the nonpolitical purpose of that money could be.”

The charitable foundation that donated to Right to Rise lists three US Sugar executives as its trustees. Disclosure forms from 2010 to 2014 don’t list any charity spending, and as of 10/2014, the charity had just $3,296 in assets. That means the foundation would have had to collect at least $501,704 in tax-deductible donations since then, to finance a donation of the size reported in the original Right to Rise filing.

Nonprofit groups don’t need to disclose their donors publicly. That’s a key reason that campaign finance reformers have criticized recent US Supreme Court decisions that allow nonprofits organized under different rules, known as section 501(c)(4), to funnel money into Super PACS from secret donors. But donations to these groups aren’t tax deductible, which is one of they key distinctions between them and 501(c)(3) groups like the US Sugar Charitable Trust when it comes to allowed political activities.

“We’re moving quickly to a kind of wild west atmosphere,” Vandewalker says of recent Supreme Court decisions on campaign finance. “The FEC is not enforcing the law like it used to, and neither is the IRS for that matter, and some groups are seeing what they can get away with.”