New York City’s mayor, Michael Bloomberg, is now the first person in history to have given more than a billion dollars to a single educational institution—his undergraduate alma mater, Johns Hopkins University. His generosity is apparently rooted in the transformation the university inspired in the young Bloomberg, who arrived on campus a middling high school student and left with an engineering degree and his first political victory—student body class president.

Arguably, Hopkins was instrumental in making Bloomberg into an entrepreneur and, as one of the greatest mayors on the planet, a model for those interested in city-led political change. At Hopkins he learned to “organize those around him” and “discovered the addictive power of the limelight.”

But by his own admission, Hopkins “took a chance” on a then 18-year-old Bloomberg, who had a “C” average in high school and listed the math club as his sole extra-curricular activity. In today’s world of cut-throat admissions policies, would the next Bloomberg get in?

The chances seem slim. In 1960, when he arrived on campus, US national university rankings didn’t even exist and, having limited information, students were more likely to attend an institution close to home. In 2012, young Bloomberg would be applying to a university ranked 13th in the country by US News and World Report (which publishes the standard rankings in America), with an acceptance rate of just 18%.

Paradoxically, the more selective they are, the more US universities like to emphasize that they take a “holistic” view of incoming freshmen, giving more weight to candidates’ “deeper qualities” as well as academic grades. This process selects first for whether or not a student is a good “fit” for the needs of a university. This may favor members of minority groups (whether that’s athletes, flautists or ethnic minorities) and those who can afford to pay full tuition.

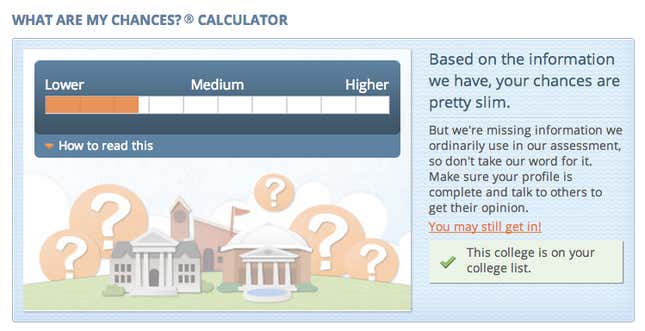

But grades still matter. According to Cappex.com, a site that helps help high school students determine their odds of being accepted to various universities, a student with Bloomberg’s hypothetical grade-point average of 2.3 (a “perfect” score is 4.0) would have “slim” chances of making it in.

Those odds are considerably worse than they would have been in 1960. It’s conventional wisdom that this is due to a US demographic bubble of young people that reached its maximum in 2009, flooding universities with applications. That bubble was the “baby boomlet,” or the children of the post-WWII baby boomers; you may also know them as Millennials.

But according to a 2009 paper by Caroline Hoxby, director of the Economics of Education Program for the National Bureau of Economic Research, America’s elite universities expanded their class sizes enough to accommodate the demographic boomlet. They are over-subscribed, she says, solely because of growing demand from a broader pool of foreign and domestic (but geographically far-flung) students, who naturally all want to get into the best schools. The number of students from abroad who are now studying at US universities was at a record high of 764,495 in the 2011/12 academic year, up 31% from a decade ago, driven primarily by an influx from China.

Measuring the wrong thing

A spokesperson for Hopkins told me that “it’s impossible to know” if Bloomberg would get into the university today, and added that “Johns Hopkins and other highly selective universities look for indications of potential, indications that an applicant has the ability and character to make a real difference in the world.”

The trouble is, admissions officers do not in fact have a direct incentive to look for the kinds of students the Hopkins spokesperson says they do. All colleges want to be ranked as highly as possible. Rankings are calculated using a methodology that relies on factors such as the test scores of the students it admits, its retention rate, its graduation rate, its academic reputation, how much money it has… but not the quality of the graduates it produces. In short, the rankings evaluate the past performance of a college’s students, but not their future. As Microsoft founder (and Harvard drop-out) Bill Gates noted in a recent article (paywall):

Currently, college rankings are focused on inputs—the scores and quality of students entering college—and on judgments and prejudices about a school’s “reputation.” Students would be better served by measures of which colleges were best preparing their graduates for the job market. They then could know where they would get the most for their tuition money.

So while America’s elite colleges might be looking to produce alumni like Michael Bloomberg, they aren’t necessarily measuring the factors that would allow them to determine if they’re succeeding—never mind the fact that they probably aren’t letting those future Bloombergs in, in the first place.