Amazon can change lives. Nearly anything you need can arrive at your doorstep in as little as a few minutes to a few days.

For $99 a year, through Amazon Prime, you can receive a wide array of items in two days, for no additional costs. Thousands of movies and original TV shows are available for screening at no additional cost.

It’s fast, efficient, convenient. The service is outstanding, and reflects the ”customer obsession” Amazon promotes as its number one value. For a customer, Amazon is excellent.

But for many Amazonians (those who work at the company), Amazon is life-changing in a much less positive way. According to a recent New York Times piece, the working conditions at the US retail giant are grueling. Employees are overworked and held to unrealistic productivity standards. Amazonians are expected to be available during holidays, pay for business calls and other expenses out of pocket, and are timed as they pack goods for shipment to ensure the highest productivity. There’s also the nightmare stories of cancer patients accused of low productivity, of the mother of a stillborn child made to leave for a business trip straight after the delivery, of managers crying at their desks.

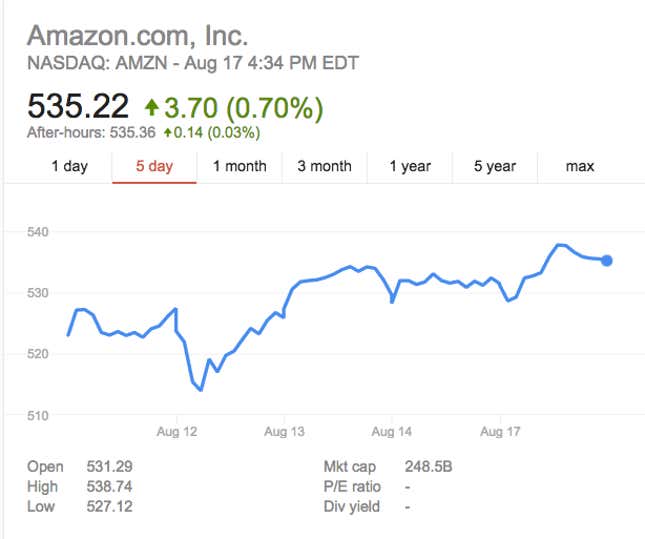

It’s upsetting to read, and not the first time such allegations have been leveled against the company. That Amazon is not a good place to work has been rumored for a while. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO, has rejected some of the accusations, and said the company won’t tolerate “the shockingly callous management practices” described by the Times, but Amazon’s stock emerged nearly unaffected from the noise later today.

The company representatives interviewed from the story, as well as some employees (former and current), explain the management practices in the name of innovation, disruption, and the continuous quest of more efficient solutions.

But there’s nothing innovative about this: it is, at its core, nothing more than cost-cutting in disguise. What other companies accomplish by outsourcing, Amazon does by squeezing every last drop of energy out of its workers. Because if you can’t pay workers $1.50 an hour—as do the companies that Apple outsources to—then the next best is to make sure they out-worth their wages.

It’s appalling, but point your fingers away from evil bosses: Terrible work conditions at Amazon exist first and foremost because we like—we really, really like—to get things cheap.

We’ve come to expect mani-pedi specials in New York at $19.99. Two-hour home cleaning for under $30. To buy our stuff online, pay less than we would at a store, have it delivered in two days, even on Sunday, for less than 28 cents a day.

We want it all and we want to pay the least amount of money for it. It’s not different from fast fashion or food production: Cheap always comes at a cost. In the service industry (online and off), employees often pay the price we’re not willing to: Amazon’s defense is right—the company isn’t the outlier, this is the standard.

Shaming bad bosses is fine. Demanding accountability is good. But—sorry, everyone—we need to be ready to pay more for things that are too cheap to be good. Our outrage is hypocritical: This is the system we buy into, the one that we want.

Unless we change that.

What if we were willing to pay 40 cents a day, each year for Amazon Prime ($149 a year), with the specific assurance that the extra goes toward a better life for those who make it such an excellent service? How about, cynical as it may sound, companies start making fair treatment of their employees an added benefit, and we all just pay for it?

That’s actual innovation—if you’re ready to embrace it.