Clarice Lispector was a woman plagued by “the hellish grandeur of life.” Throughout her career the Brazilian author and journalist showed a fascination for the mundane, as well as a desperation to quiet her mind and achieve a semblance of normalcy.

Lispector died of cancer in 1977 without ever realizing that goal, leaving behind a body of bizarre, challenging, and dazzling writing that has become a part of the literary canon within Brazil and has built a small but fierce cult following among the literary cognoscenti elsewhere. Despite this acclaim, however, the enigmatic and statuesque Lispector remains relatively unknown internationally.

The Complete Stories, released Aug. 25 by New Directions and translated into English by Katrina Dodson, gives readers access to all 86 of her short stories in one place for the first time in any language, and has been greeted with a flurry of belated and enthusiastic appreciation.

An unknown legend

With this new volume, the woman known in some circles simply as “Clarice” has another chance at the mainstream international consumer.

But back home, Lispector needs no introduction. Her fans are almost rabid in their devotion to her. In the decades following her death, her popularity has exploded, and her famously beautiful face has become iconic: She has appeared on stamps and is quoted constantly on cheesy inspirational posters. A Twitter account that posts quotes by her has a million followers. Brazilian rap star Filipe Ret has her face tattooed prominently on his bicep.

She’s a favorite of critics internationally as well: Routinely compared to Jorge Luis Borges, Vladimir Nabokov, and James Joyce, Lispector is hailed by many literati as Brazil’s greatest contemporary writer. Benjamin Moser, Lispector’s biographer and champion in the English world, as well as the editor of the new collection, is often quoted as saying she is the most important Jewish writer in the world since Kafka.

A sphinx and a housewife

Part of Lispector’s aura of intrigue comes from her beauty, glamour, and strange public persona. Of Eastern European Jewish origin, she was transplanted to Brazil as a small child.

In his biography of Lispector, Why this World, Moser paints her as a person full of contradictions. He writes:

“She herself once wrote, ‘I am so mysterious that I don’t even understand myself.’

‘My mystery,’ she insisted elsewhere, ‘is that I have no mystery.’”

Still, he adds, “To general bemusement, she insisted that she was a simple housewife, and those who arrived expecting to encounter a Sphinx just as often found a Jewish mother offering them cake and Coca-Cola.”

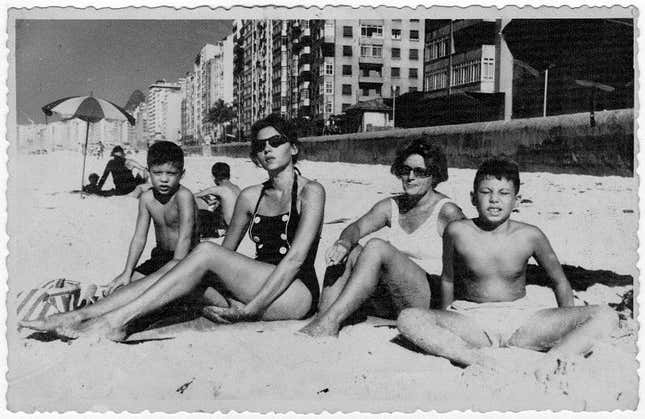

Lispector was in fact a housewife (though hardly a simple one). For sixteen years she was married to a Brazilian diplomat, with whom she had two sons, and she never considered herself a professional writer. (Despite that, she wrote nine novels along with her 80-plus short stories, and worked as a fashion journalist.)

Her personal style added to her mystique: Writing about her in 2005, Gregory Rabassa said, “I was flabbergasted to meet that rare person who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virginia Woolf.”

It would be unfair to think Lispector’s association with beauty and fashion matter only because she is a female writer. In her work, they function as a kind of intentional opaqueness. As Stephanie LaCava writes for the LA Review of Books:

“Throughout her work, as Moser notes in his biography, there are moments when makeup and beauty figure as the real, the solid, in the category of knowable. These seeming superficialities are actually conduits or tools, masking—protecting—the unknowable soul; they are links to sanity.”

In her only TV interview, Lispector is visibly uncomfortable, nervously smoking, and we get a sense that her famous glamour is an armor of cool, barely concealing a clamoring anxiety.

Stuck in translation

Moser says Lispector enjoys a kind of “folk popularity” in Brazil, where her work is required reading on the national university entrance exams called Vestibular, similar to the French baccalauréat.

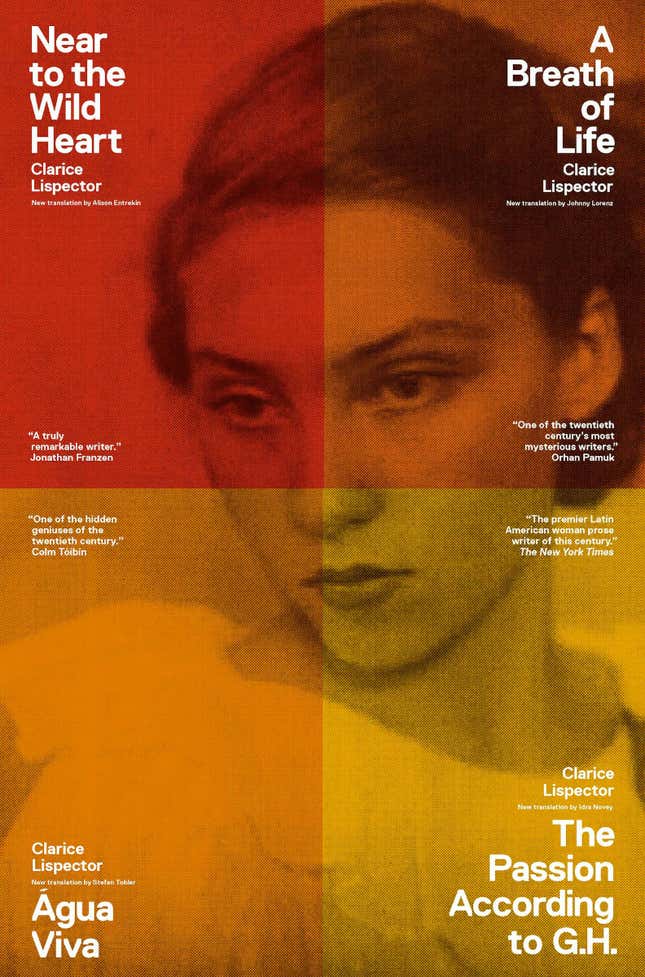

So why hasn’t she caught on in the rest of the world? Moser says the answer lies in the quality of previous translations, which he considers not up to snuff. He has spent the last 12 years trying to revive interest in her, leading efforts to have her works re-translated. From 2011 to 2012 he edited or translated new versions of five of her novels (blurbed by the likes of Jonathan Franzen, Orhan Pamuk, and Colm Tóibín), and he’s currently working on the last four.

The difficulty of translating Lispector is partly due to the fact that even in her native Portuguese, she often created fake idioms and distorted normal ones, her translator, Katrina Dodson, tells Quartz. Dodson gives an example from the story “Silence,” in which Lispector uses the phrase “ponto do trigo,” or “point of wheat,” in a sentence she translates as “I never thought that the world and I would reach this point of wheat.”

“That sounds as if it’s a known expression but [it] isn’t at all,” Dodson writes in an email. “We must have asked at least six Brazilians what it meant and no one could say.” She writes in the translator’s note that appears in the new collection, “These unexpected choices often make you do a double-take or blur your reading even if you don’t stumble.”

The chaos and a contract

Hidden between the layers of Lispector’s at-times-impenetrable prose lies one story we’re all familiar with: The chaos of the everyday.

Lispector’s characters struggle deeply with seeing madness in the mundane, which threatens to consume them. In Lispector’s story “Love,” an otherwise perfectly sane character is seized with emotion upon a blind man chewing gum. “She had pacified life so well, taken such care for it not to explode,” writes Lispector. Yet one look “had plunged the world into dark voraciousness.”

In her last novel, The Hour of the Star, the narrator wonders, “Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?”

The blurred lines in Lispector’s language are reflected in the themes in her work, in which she strives to temper the frisson of everyday life. As LaCava writes in the LA Review of Books:

Lispector’s work often explores the specific domestic conventions to which women are expected to adhere — and not because, as one might expect, she necessarily wishes to destroy them. In fact, Lispector seems to wish she could be one of the happy housewives satisfied by days occupied with decorative arrangements. Except, she is plagued by knowledge and a mystic talent for words.