The Arctic is melting rapidly. Who cares? Anyone who is concerned about the rising price of food, lives near the coast, shoveled snow all winter, can’t water their lawn anymore, pays a bigger premium now for property insurance or enjoys eating seafood. Did we leave anyone out?

Apparently so, yet this group of people should care as much as anyone. The House of Representatives earlier this year passed a budget that funds NASA’s earth sciences research at $1.45 billion—down 18% from $1.77 billion in fiscal year 2015 and well below (26%) the White House request of $1.95 billion in 2016. NASA’s earth sciences work and the National Science Foundation’s geosciences budget fund much of the research US scientists do on the Arctic.

These programs provide data that will help pin down the scope of the many impacts from a changing Arctic and help decision-makers in communities across the country prepare for them.

Most Americans are aware that Arctic ice is disappearing, but few appreciate the enormity of its effects on their daily lives. And as time goes on, effects from the changing Arctic will increasingly be in our headlines.

Wrong direction

Back in the 1850s, the Arctic was in the news when the Royal Navy searched for Sir John Franklin’s missing Northwest Passage expedition, a failed attempt to plot a path from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the Arctic Ocean.

Today, Arctic navigation is a hot topic again as sea ice disappears, raising new opportunities and challenges. In addition to satisfying our longstanding fascination with all things Arctic, today’s interest is—or should be—also highly practical.

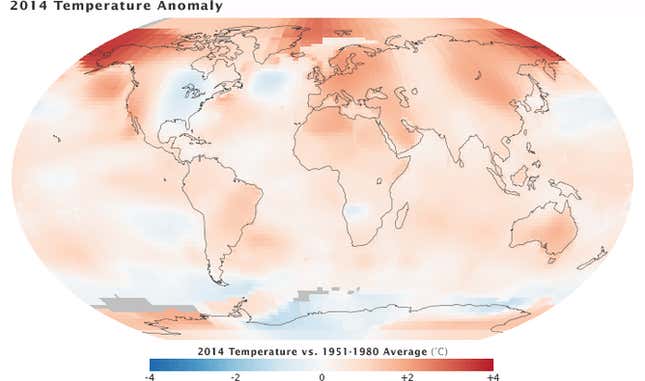

California’s ongoing drought and the East Coast’s snow-filled winter of 2014/2015 are in part the result of changing weather patterns driven by the Arctic meltdown. New studies suggest that strong, persistent northward swings in the jet stream—like the one that has been sitting off the west coast of North America almost continuously since late 2013 and is responsible for drought and the intense wildfire season in the western US—are initiated by ocean temperature patterns that are intensified by the disproportionately warm Arctic. A similar condition exists in Eurasia, where sea-ice loss north of western Russia contributes to heat waves in Europe and colder winters in central Asia.

Meanwhile, easier navigation through Arctic waters opens the way for commerce and also for militarization, as seen in recent actions by Russia. Northern Alaska is our nation’s only Arctic territory, home to indigenous peoples, iconic animals and vast mineral and petroleum resources. Navigating the competing, conflicting and sometimes common interests of these facets of our Arctic requires solid science and a willingness to act on the knowledge it affords.

So it is ironic that Arctic research budgets are shrinking at precisely the time when their results are of greater relevance to national interests than ever before.

The United States is a superpower, yet lags behind Finland and Korea when it comes to icebreaker capacity. Satellites essential for monitoring Arctic change are aging, retiring and leaving gaps in our observing capabilities. Young scientists will see little attraction to pursuing careers in a region where funding is declining, draining the human resources needed to understand just how a changing Arctic affects us all.

And a failure to identify the risks of Arctic meltdown leaves us unable to understand the causes of—and thus respond effectively to—droughts and extreme weather nationwide with ties to the Arctic.

Our current path risks leaving us unable to understand the impacts of—and thus manage responsibly—the development of Arctic resources. A decline in Arctic research diminishes our leadership in the region and makes us increasingly dependent on the activities, talents and capacity of other nations, whose interests may not align with our own.

More broadly, the Arctic example is, in our opinion, but a symptom of a wider dismantling of the United States’ world-leading scientific capacity.

Stepping up to challenge

Scientific research is not a luxury to be indulged. It is an essential contributor to our national well-being, helping us avoid costly mistakes while finding new ways to improve our security, our economy and our quality of life. For example, precipitation patterns can inform authorities of water supplies for drinking and agriculture, temperature patterns dictate energy needs for cooling and heating, and better knowledge of extreme weather events can reduce disruption in all aspects of life.

Some of our political leaders are well aware of the importance to studying the Earth. In response to the proposed cuts, one member of Congress wrote: “It’s hard to believe that in order to serve an ideological agenda, the majority is willing to slash the science that helps us have a better understanding of our home planet.”

While scientists need to better communicate the relevance of our work to society, the public needs to better appreciate that scientific research—funded through a rigorous, competitive process that is free from the fetters of ideology, politics, and short-term economic gains—benefits all of us.

The loss of Franklin, his men, and his ships was a tragedy, but their legacy is nonetheless one of courage, risk and commitment.

Today, Congress is taking us on a course toward an Arctic legacy of myopia, feebleness and ignorance. Rather than denying the changes that affect us all, they should be steering our national policies toward scientific excellence and vigorous action on challenges such as Arctic meltdown and its impacts. Nowhere is the evidence clearer; never has the need for research been more urgent. We ignore the Arctic at our peril.

Brendan Kelly, the chief scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, contributed to this article.