In 1957, the Thames—the huge river that flows though the city of London—was declared biologically dead. And for most of London’s history, its river has been more of a hazard than a habitat. Effluent from Victorian sewers flowed into it. Chemicals from the prolific 19th-century laundries that lined the banks killed off most of the fish, and pretty much anything else that formerly lived in what came to be called the Great Stink.

Yet now it’s teaming not just with fish but with marine mammals including seals and porpoises—and even the occasional whale.

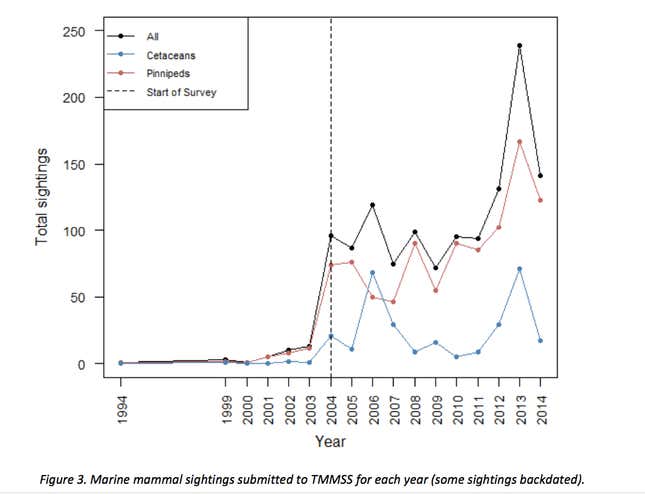

The Zoological Society of London today released the results of a 10-year survey that points to the presence of thousands of animals, via data gathered from public sightings. Harbor seals and other pinnipeds (certain kinds of carnivorous aquatic mammals) are the most common. Cetaceans including whales, dolphins, and porpoises are also present in large numbers.

The change began in the 1990s, with the passing of regulations relating the water industry and the treatment of waste water in urban areas, which imposed a duty on sewage companies to maintain adequate collecting systems and treatment plants. In 1996, the government’s Environment Agency gained oversight of the river.

The report from ZSL, which also runs London Zoo, suggests that now mammals in the Thames, they are managing to survive and even thrive despite a long list of problems, including continued pollution, disease, noise disturbance, collision with boats, entanglement in fishing gear, and habitat loss.

“People are often surprised to hear that marine mammals are regularly spotted in central London,” said the ZSL’s Joanna Barker, the European conservation projects manager. “As a top predator, their presence is a good sign that the Thames is getting cleaner and supporting many fish species.”

The creatures do not stay confined to the outer reaches of the Thames, where it meets the sea, but venture far upstream. Seals were reportedly sighted as far upstream as Hampton Court Palace, the report said, with the highest concentration around the financial hub of Canary Wharf. Harbour porpoises and bottlenose dolphins were also spotted but made it a little less far upstream. Whales were sited in the river reaches nearer the sea—though one errant northern bottlenose whale made it as far as Battersea Bridge, very close to the Houses of Parliament, and died during a rescue operation.

The enthusiastic public engagement is in contrast to the city’s historical relationship with sea creatures. Seals and dolphins have both been shot at over the centuries. “The earliest record of a marine mammal in the River Thames dates back to 1240, when a whale was chased up the river to Mortlake and butchered,” the report said.