Like the United States and Blanch DuBois, heavily indebted European countries have long depended on strangers, if not for kindness, then for steady inbound shipments of cash to balance off its persistent deficits. In other words, countries with relatively large debt loads, like Italy, relied on the money borrowed in the bond market from cash-rich investors like German insurance companies and Dutch pension plans.

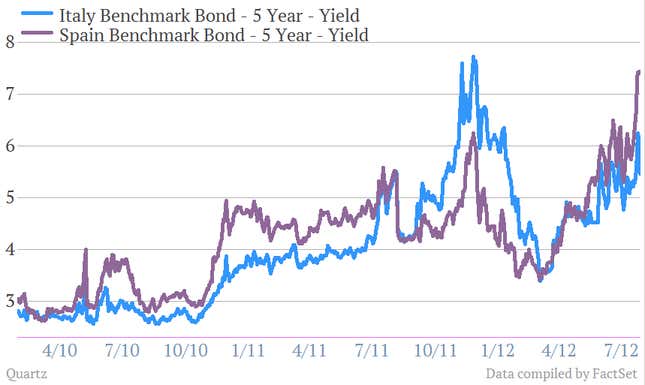

But over the last couple of years, that system stopped working as part of the European debt crisis. Global investors, growing worried about the prospect of a euro-zone breakup, largely stopped lending to worrisome countries. That sent the price of those government bonds down sharply. Yields, or government borrowing costs, move in the opposite direction of those prices, so they skyrocketed, at least through last July. Just look. Here are on five-year Spanish and Italian government bonds over the last couple years through July:

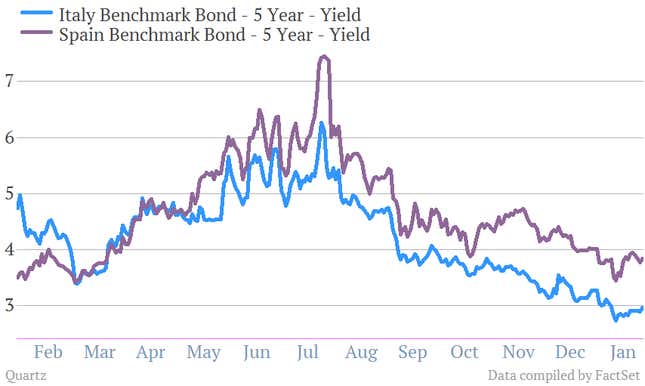

Then in July, newly minted European Central Bank President Mario Draghi changed the dynamic drastically, promising that the central bank would do “whatever it takes” to ensure the euro zone remains intact. He later backed up the statement and essentially said the European Central Bank would buy government bonds of troubled countries whenever the situation got bad enough for those countries to ask for help. (That promise—which, by the way, hasn’t actually been used yet—is known as Outright Monetary Transactions, or OMT.)

Draghi’s gambit has got to be one of the most successful from a central banker in recent memory. Bond yields for the troubled countries collapsed, as the prices of the bonds soared. Have a look. Yields moved sharply lower after Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech in July:

The drop in yields is evidence of investor confidence. Global investors are willing to lend their money to the troubled nations again. The Financial Times reports today:

Total net private inflows into the periphery countries totalled €93bn in the last four months of 2012, according to ING. In contrast, the first eight months had seen €406bn flow out of the five countries, equivalent to almost 20 per cent of gross domestic product in the periphery economies. In 2011, outflows from the periphery totalled €300bn.

“There is still a way to go, but there has been a significant reversal of the capital flight,” said Martin van Vliet, ING economist. “If you look at the outflow in the first eight months of last year, it was scary. Trust is hard to gain and easy to lose.”