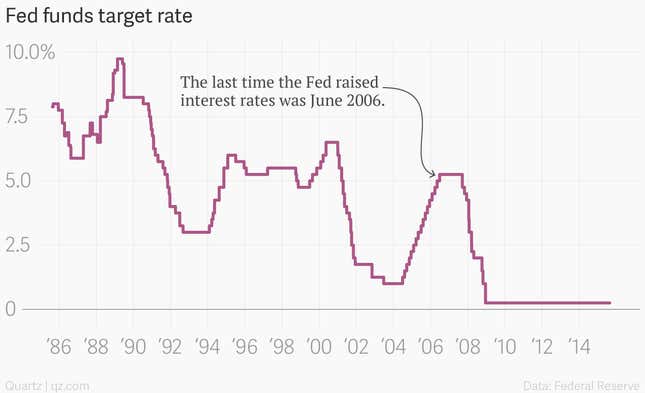

Before the US housing crisis, before the US financial crisis, before the European debt crisis, the Federal Reserve used to raise interest rates.

It’s been more than nine years since the US central bank hiked rates—which is a way policymakers tap the brakes on economic growth. In fact, the Fed has been doing the opposite. It’s been flooring the gas pedal on the economy (or at least trying to) by pushing interest rates to nearly 0%.

But there’s a huge desire among a lot of people to get back to the “good old days” of slowing things down. Why?

Jobs

People who think raising rates is a good idea—they’re known as “hawks” in financial-ese—tend to point to a bunch of things. But for the most part, they note that the US unemployment rate has fallen sharply. It touched 5.1% in August, down from a crisis-era peak of 10% in late 2009.

That’s below the average of 6% for the last 20 years. In other words, unemployment is pretty much back to normal. From their perspective, the Fed has done its job. Now the central bank should try to get back to a more ordinary interest rate policy. Sounds reasonable enough.

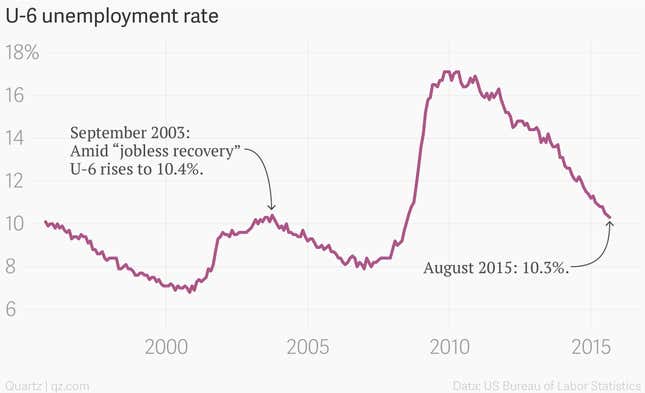

But the US unemployment rate is just one of the ways you can measure the health of US labor markets. And not all these metrics look so hot. For instance, a broader gauge of unemployment known as the U-6 rate includes workers who’ve stopped looking for work because they don’t think they can get a job, or those who are working part-time because they can’t find full-time work. The U-6 gauge also shows improvement, falling to 10.3% in August.

But that’s not terrific. A reading of 10.3% is on par with the worst days of the “jobless recovery” after the 2001-02 recession. That’s a far cry from the “maximum employment” that is a Federal Reserve objective set by law.

Soft inflation

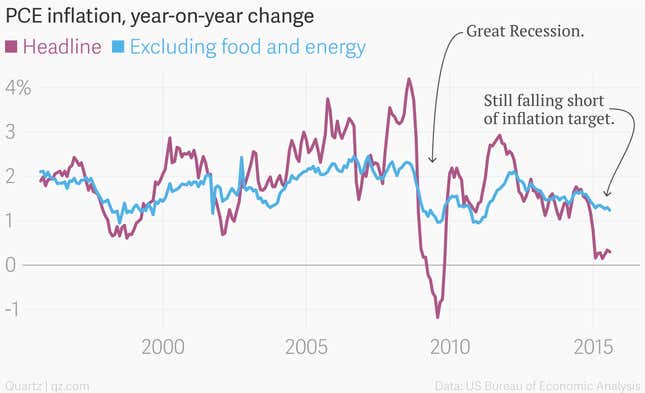

The law governing the Fed also sets other goals, including price stability. The Fed’s super-easy-money policy hasn’t quite gotten it back to the right spot either.

In practice, the Fed aims to hit an inflation target—defined by the so-called PCE inflation gauge, excluding food and energy—of roughly 2% a year. It’s not there yet. In fact, it’s going in the wrong direction. PCE inflation, excluding food and energy, was 1.2% in July, the most recent data available. (This is the Fed’s most important gauge of inflation.) That’s the lowest since 2011, when the US was scrambling to escape the deflationary vortex set off by the Great Recession and financial crisis.

The dollar

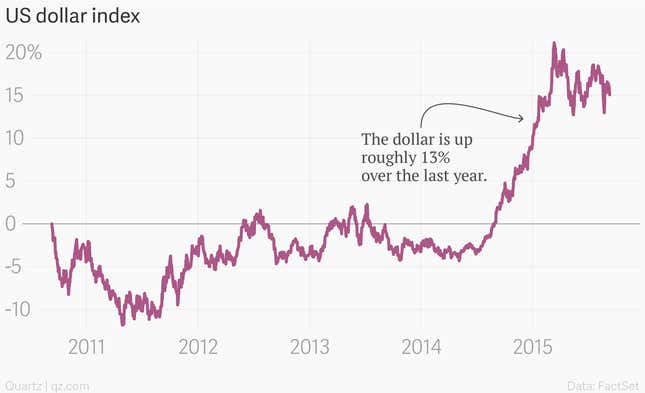

Now, global economic and financial forces are threatening to pull the US back into deflation once again. For instance, as expectations have grown that the Fed might raise interest rates, investors grabbed dollars in currency markets, pushing up its value. (You can think about interest rates as how much you earn for holding dollars, so higher rates make them more desirable.)

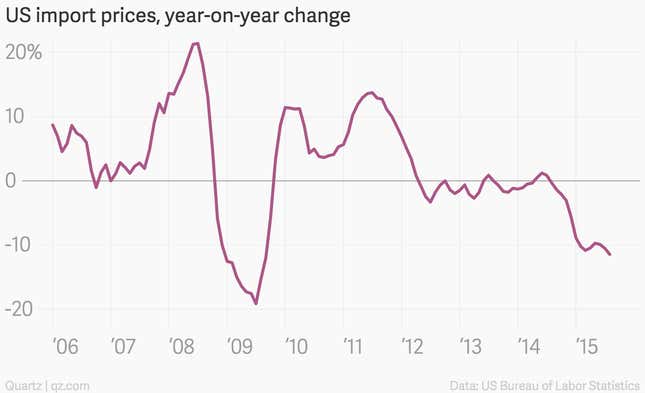

The rising dollar adds to deflation worries, as it makes imports cheaper.

China

Weak demand in China has factories there sharply cutting prices on goods, a lot of which are eventually imported to the US. This deflationary pressure is another reason why prices are having trouble climbing to the Fed’s target. And that argues for holding off on raising rates, at least until the economy is running hot enough to offset the downdrafts from overseas.

Financial markets

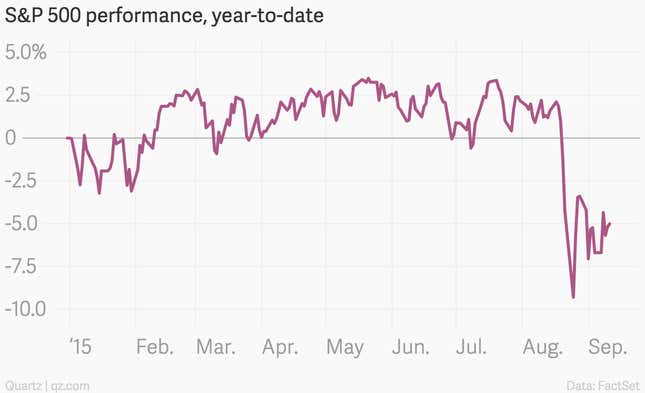

Meanwhile, the slowdown in China has sent financial markets into a tizzy lately. While the Fed wants to avoid the appearance of propping up stocks every time the market has a hiccup, the central bank is also concerned about how a decline in the market—the S&P 500 is down about 5% so far this year—can bleed into the real economy by making consumers less confident.

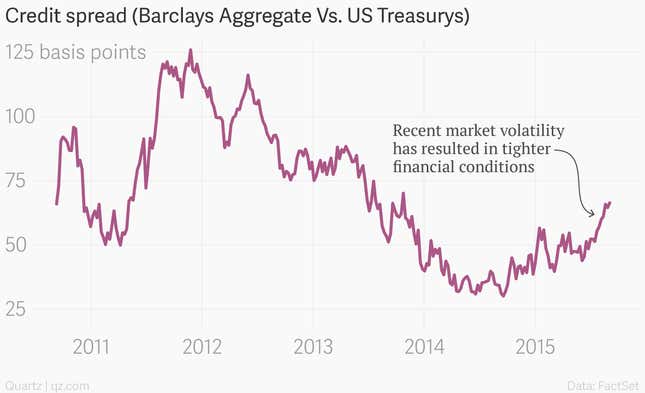

Even more important, the US corporate bond market fell along with the stock market. That widened the spread between yields on corporate bonds and the safety benchmark of US Treasurys. Translation? It’s gotten more expensive for businesses to borrow.

Widening credit spreads aren’t a red flag to worry about. When markets are choppy, investors get tighter with their money. But, effectively, it means borrowing costs have already gone up a little bit—which is exactly what the Fed would be doing if it raised interest rates.

In other words, the Fed doesn’t have to hike rates. The global economy and financial markets have already done it. The US central bank would be wise to hold its fire and see how the US economy—still finding its footing after the Great Recession—fares in response, before piling on an interest rate increase of its own.