This item has been corrected.

Much is made of China “going green.” But maybe more attention should be paid to China going to Greenland. The island nation’s government is considering a $2.35 billion iron ore mining project backed by Chinese steelmakers that could bring in some 5,000 Chinese workers and would see around 15 million tonnes (16.5 million tons) of iron more shipped to China annually. It would be Greenland’s largest industrial development, bringing in more than its current annual GDP.

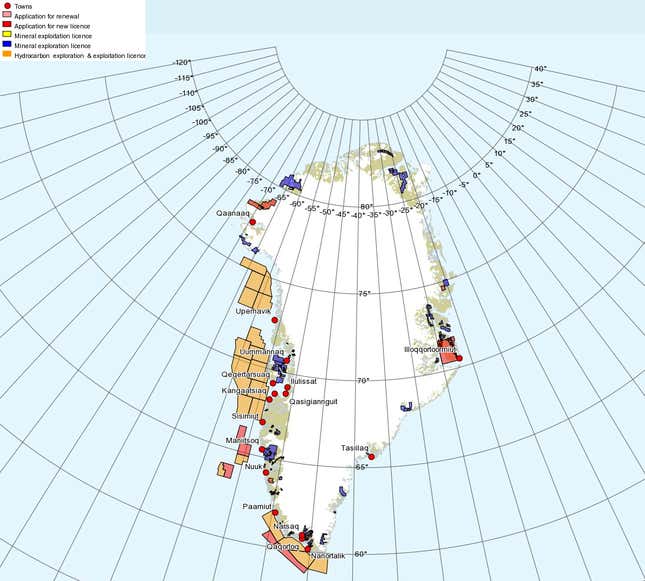

The Chinese are arriving just in time. Though Australian and Canadian companies currently dominate in exploration of Greenland’s natural resources, actual mining has been kept to a minimum so far.

No longer. Prime minister Kuupik Kleist sees extraction of Greenland’s abundant natural resources as a way to shake free of Denmark—the island of 57,000 people is a semi-autonomous territory. A bill passed in December introduced a framework to open up extraction of these resources, which the peel-back of melting glaciers is making increasingly plentiful, to foreign wildcatters.

The bill will also allow companies to hire foreign laborers at lower pay than that enjoyed by Greenlandic workers. That will be a big boon to companies hoping to use Chinese miners. The aforementioned iron ore mine project would boost Greenland’s population by 4%, and that’s not even counting the potential influx of some 3,000 Chinese workers at an aluminum smelting plant and two hydroelectric projects that Alcoa is reportedly mooting. This isn’t wholly uncontroversial, though, and Greenland’s parliamentary election in March could see the law revoked. Still Kleist says he does “not see thousands of Chinese workers in the country as a threat.”

Chinese workers aren’t the only worry, though. A far bigger concern is the rare earths issue.

China controls around 97% of the world’s supply of these strategically key metals, which are used in the batteries for cell phones and hybrid cars, as well as in weapons, medical devices and many other things. After China began limiting its rare earth exports in 2011, prices for the elements have spiked. Greenland is thought to have some of the largest deposits of rare earth elements—one southern Greenland deposit may yield more than one-tenth of the world’s current deposit volume.

And Kleist recently rejected the European Union’s request that Greenland restrict mining of its rare earth deposits. (Though Denmark is an EU member, Greenland is not.) Martin Breum, an expert on Greenland’s extractive industries, told Reuters that this was a source of alarm for Western governments.

“Potential Chinese control of the rare earth elements in Greenland is scary to a lot of governments in the Western world,” Breum said. ”Rare earth elements are of crucial importance to [many of their] industries.”

There’s still more at stake in China’s Arctic aspirations, writes Paula Briscoe, National Intelligence Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations:

If Greenland, a littoral Arctic territory, becomes increasingly dependent on Chinese investment, Beijing’s influence in Greenland and Arctic affairs also grows. China’s application to be elevated to permanent observer status is on the Arctic Council’s agenda in 2013, and Greenland’s administrator, Denmark, is already a supporter of China’s bid. Should Greenland become fully autonomous, and then a likely permanent member of the Arctic Council—two possibilities made more likely by heavy Chinese investment—China’s increased influence in Greenland could help buy Beijing a proxy voice in Arctic matters.

In other words, Greenland’s bid for political independence could help allay China’s resource dependence—and put it literally at the top of the world in terms of geopolitical clout.

Correction (February 11, 10:00 AM ET): A previous version of this story said that the Greenland government had approved the $2.35-billion iron ore project back by Chinese steelmakers. The article has been corrected to reflect that the government has not yet granted a license for the project.