The Pope, Xi, and Obama walk into a bar: Who lectures the other two on human rights?

The east coast of the United States is overflowing with influential leaders this week and next. Pope Francis and Chinese president Xi Jinping already have met with US president Barack Obama in Washington. Today (Sept. 25) the pontiff is in New York, where he spoke to the UN General Assembly; New York also is on the itineraries of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and Russian president Vladimir Putin.

The east coast of the United States is overflowing with influential leaders this week and next. Pope Francis and Chinese president Xi Jinping already have met with US president Barack Obama in Washington. Today (Sept. 25) the pontiff is in New York, where he spoke to the UN General Assembly; New York also is on the itineraries of Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Amid all of these meetings and speeches, the elephant in the room is human rights. And at this point in history, it is hard not to wonder which world leader has the moral authority to push the others on the issue.

Is it the US, with its police brutality and racism, its drone attacks and torture? The Catholic church, with its long history of child sexual abuse and cover-ups? China with its growing crackdown on human rights lawyers and free speech, and its constant suppression on the rights of Tibetans and Uighurs?

Laws, not morality

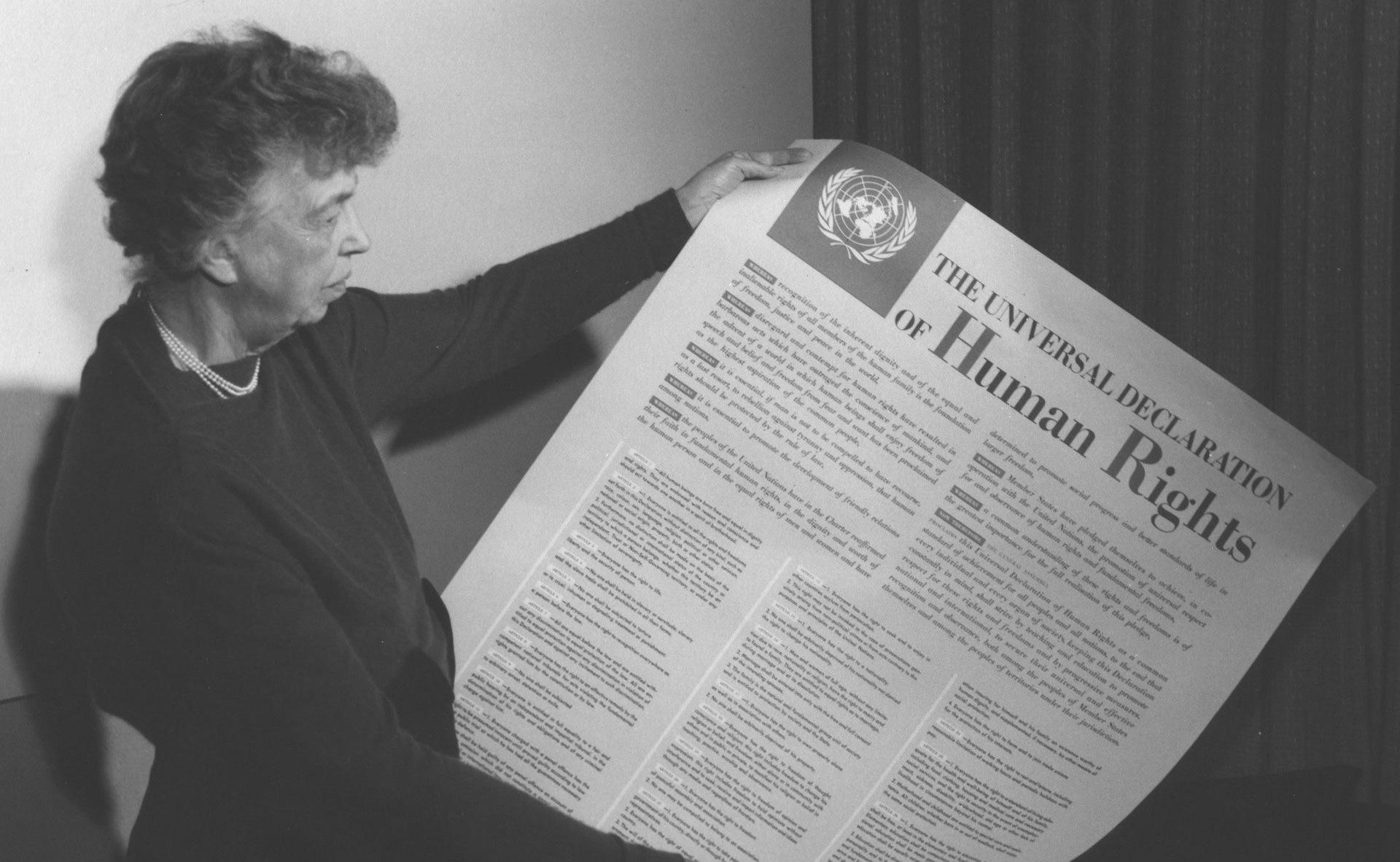

For many of those who spend their lives defending human rights, the UN’s Universal Declaration on Human Rights serves as the bedrock of their arguments. Signed by nearly every member of the UN, and supported by the Holy See, the document states that:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

It lays down specifics from banning torture to calling for fair trials.

None of the signatories follow it to the letter, activists say. But this doesn’t take the issue off the table.

“We reject idea that countries have to have a perfect human rights record to criticize other governments,” Nicholas Bequelin, Amnesty International’s director for East Asia tells Quartz. “If we were to follow this road, human rights could never be discussed since no country has a perfect human rights record.”

For activists, the declaration itself—with its clear standards on what constitutes torture, for example—is more important than the specific track records of countries trying to take a leadership role on the issue.

“We do our work in the world of law, we do our work based on international law, so its not in the squishy realm of morals and relativity,” Sophie Richardson, the China director of Human Rights Watch, tells Quartz.

What is a right?

Of course, not every country or religious leader understands human rights the same way. Lee Kuan Yew, the late Singaporean prime minister, argued in the 1990s that international human rights standards were biased toward the West and contrary to many “Asian values,” while Islamic countries have argued that they violate Sharia law.

In China, rather than saying outright that Western exports of human rights standards don’t apply to Asian countries, the leadership instead emphasizes the issue of practicality. Characterizing its country as being too poor to “afford” conveniences like freedom of expression and religion, China argues it is making “tremendous” progress on human rights as it lifts people out of poverty.

At some level, there is general agreement over what human rights comprise. In a 1997 speech, philosopher Amartya Sen emphasized common ground on human rights by arguing that Lee’s Asian values were not exclusively Asian, and Western values not exclusively Western. This is supported by opinion surveys, like one released in 2011 by the Council on Foreign Relations (based on 2008 data), that shows broad support for the UN’s human rights activities across the globe.

Most everybody seems to agree that a repeat of the genocidal events of the 20th century that brought about the formalization of human rights should be avoided at all costs. But in order for anybody to wield moral authority over others, it’s not enough to just agree on the rules—the wielder must also be seen as an honest practitioner of them. That’s where the relationship between the Pope, Xi, and Obama gets hairier.

Rights have become a political battle

The pope is in New York after a visit to Cuba, where he neglected to mention human rights or Cuba’s dispiriting record on them. His failure to broach the topic in Cuba disappointed activists and Cuban dissidents, but the topic was back on the pontiff’s front burner by the time he arrived in the US, and delivered what amounted to an address on human rights to the US Congress.

The pope generally has been warmly welcomed in the US, but he has been getting some flak from gay rights advocates—one group displayed a huge banner along his motorcade route imploring him to lend greater support to gay Catholics. On the flip side, his passionate advocacy on climate change, the evils of capitalism, and general compassion for groups that traditionally have been marginalized by the church has earned him critics among some Catholics who consider themselves highly religious.

Meanwhile, ahead of Xi’s very first state dinner in the US, activists, politicians, and citizens from both countries were curious whether the US would broach the subject of human rights and criticize China’s record on it. Susan Rice, the US National Security Adviser, on Sept. 21 assured the press that it would.

China (which annually reprimands the US for what it sees as America’s abuse of human rights) didn’t hesitate to hit back. The US is “overly hyping and exaggerating” China’s human rights issues, Ruan Zongze, vice president of the China Institute of International Studies, told state TV channel CCTV (link in Chinese). Perhaps the most passive-aggressive state media barb came today, when the Global Times praised the “pragmatism” and “diplomatic etiquette” of UK chancellor George Osborne, for not “raising the human rights issue.”

Many governments, says Richardson at Human Rights Watch, “buy into the idea that being tough on human rights on China will cost them.” They can’t name a specific consequence, she says, but “they just assume there will be one.”

There will be more such calculations made in the coming days, over how and when to confront world leaders over human rights violations in their countries. After all, Putin’s just days away now from touching down in New York.