In the fight to end female genital cutting—the tradition of partially or totally removing a young girl’s genitalia—education paired with social engineering is a common tactic.

In countries where rates of female genital cutting (FGC) are high, educators are sent into towns or villages to explain that cutting young girls is physically and psychologically harmful. (It has been linked to infection, life-long pain associated with sex, and infertility issues, among others.) Once a certain number of families has been persuaded, they pledge to abandon the practice and a festival is held to publicly denounce FGC.

By showing that a critical mass of people are against the practice, a deeply entrenched social norm can be overturned, or so the logic goes.

But the public declaration method might not be so effective after all. A study released today (Sept. 24) in Science argues that the theory behind this approach—as well as that of many international development programs and official documents by organizations from UNICEF to the World Health Organization— may be flawed. “In many communities, it’s not obvious what the norm is at all,” researcher Charles Efferson, a senior research associate in microeconomics and experimental economics at the University of Zurich, told Quartz.

“Our results don’t support the notion that there are endogenous forces pushing all families to be alike, and that you can reliably appropriate these forces in a straightforward way. Such forces may be present to some extent, but there are also important decision-making forces that vary tremendously at the family level.”

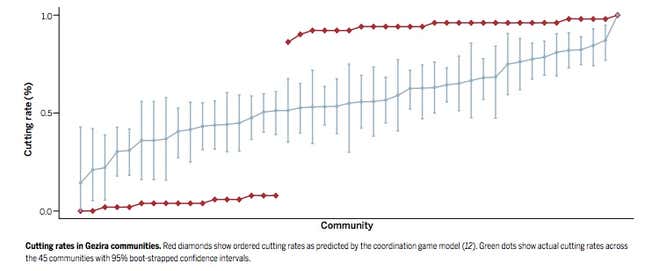

Efferson’s team visited schools in 45 different communities in the state of Gezira in Sudan, a country where up to 88% of girls and women are believed to have undergone female genital cutting. They documented cases of girls who either said they had been cut or “purified,” or whose feet were painted with henna at the beginning of term. (Henna is applied to signal that a girl has been cut, usually during the summer before entering primary school.)

The team found that cutting rates in communities were neither very high or very low, which is what you would expect if female genital mutilation were motivated by social norms. On the contrary, said Efferson: ”Our data essentially shows that cutting families and non-cutting families are right next to each other.”

Efferson says the goal of the study is not to suggest that social forces don’t play an important role, but that other motivations deserve more attention, including religion, beliefs about how gender should be marked or sexual fidelity, and relative knowledge about the health effects of FGC.

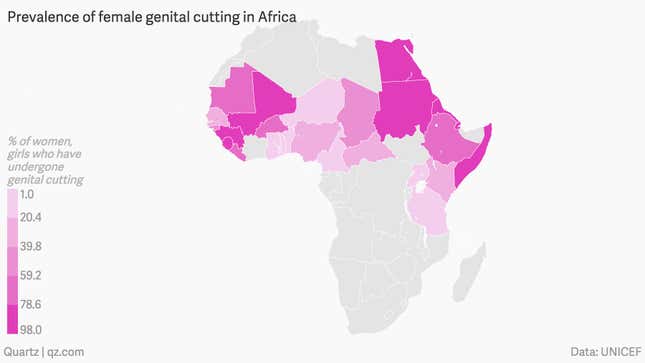

Addressing FGC as a social norm may be one reason why rates of female circumcision remain high, despite many governmental and organizational efforts to stem the practice. Worldwide, over 125 million women alive today have undergone some form of FGC. Some 30 million more are at risk, over the next decade.

According to a 2013 UNICEF report, the practice of FGC is still common in parts of Africa: