MEXICO CITY—Exactly one year ago, 43 students from a rural teachers college in the Mexican state of Guerrero disappeared after a violent confrontation with authorities. Over the past 12 months, Mexico City residents have made it clear that they won’t forget the incident until the government comes clean about what happened—or the students return alive, whatever comes first.

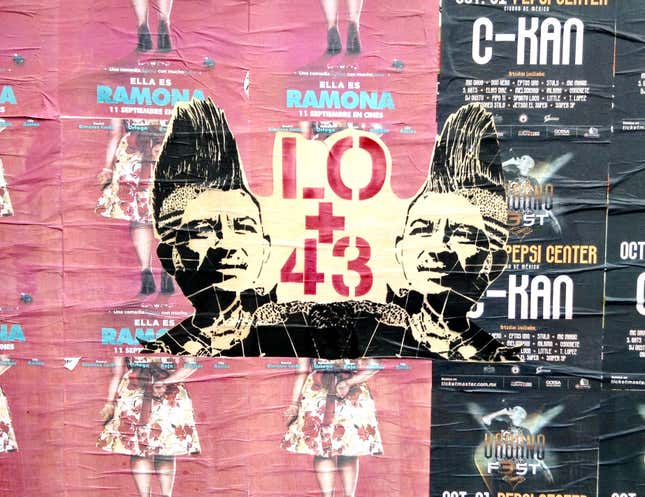

Wander the streets of Mexico’s capital and you’ll undoubtedly encounter the number 43 scrawled across statues and scribbled on the sides of buildings. Sometimes, the 43 is accompanied by the phrase “todos somos Ayotzi” (we are all Ayotzi, short for Ayotzinapa, the name of the school the students attended), or “vivos se los llevaron, con vida los queremos” (alive they took them, alive we want them).

For months, dozens of activists have been living in an encampment on a sidewalk along one of the city’s main thoroughfares, Paseo de la Reforma. Decorated on all sides with portraits of each of the missing students and signage denouncing the country’s leadership, inhabitants vow not to leave until the students are located and the current regime is dismantled. They sleep in tents, and volunteers bring food, blankets and other supplies on a daily basis.

“The towns and cities throughout Mexico need to organize and fight back for themselves,” Alejandro Alegria, 41, an economist who has been camping at protest site, told Quartz. “We need to come together. This is one expression of us doing that.”

This Saturday, which officially marks the year anniversary of the students’ disappearance, thousands are expected to march from Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto’s home, Los Pinos, to the Zocalo square at the heart of Mexico City’s historic center. Family members of the students made the five-hour journey from Guerrero earlier this week and have been camped out at the Zocalo ever since. Alegria said the students’ relatives have also frequently stayed at the encampment, which has organized a number of smaller protests along with chess tournaments, poetry nights and bike parades, throughout the past year.

To date, nobody knows exactly what happened on the night of September 26, 2014, when the students disappeared while traveling from Ayotzinapa to the nearby city of Iguala. Video footage that surfaced late last year shows a violent clash between the students and what appear to be local police officers. Six students were killed during the confrontation, and the 43 others vanished in an assumed mass kidnapping.

Mexico’s government has faced scrutiny for what many believe was a botched and inconclusive investigation. The state claimed in January that they had obtained evidence proving the students had been abducted by a local drug cartel, killed, and burned at a garbage dump. But in the months that followed, evidence contradicting those claims has begun to mount. Other investigations suggested, in fact, that the federal government may have been directly involved. A report issued earlier in September by an international panel of experts rejected authorities’ account of what happened entirely.

The report, along with the anniversary of the disappearances, comes as Peña Nieto faces a record low approval rating of 35% for his failure to effectively manage the drug violence and corruption that has devastated Mexico in recent years. For many Mexicans, the case of the 43 missing students serves as a symbol of many of the things wrong with their country.

“The images of the missing youths and their distraught families shook Mexican society, provoking hundreds of thousands to take to the streets demanding justice,” wrote Ioan Grillo in the New York Times last week. “It became a watershed case, emblematic of the killings and disappearances that have ravaged this nation.”

Indeed, Alegria and his fellow encampment members say the kidnappings and their aftermath mark the most significant case of abuse of power in Mexico since the 1968 student massacre, when military and police officers opened fire on a crowd of protesters in Mexico City’s Plaza de las Tres Culturas, killing anywhere from 30 to 300 people. “It’s a direct attack by the Mexican state against its youth,” Alegria said.

He added that he has no plans to leave the encampment any time soon. “We won’t rest until we force the government to tell the truth,” he said. “We hope the students will come back home alive once the truth is out.”

While many questions remain about what happened that late-Septmeber night, it’s clear many in Mexico aren’t ready to let the memories of ”the 43″ die just yet.