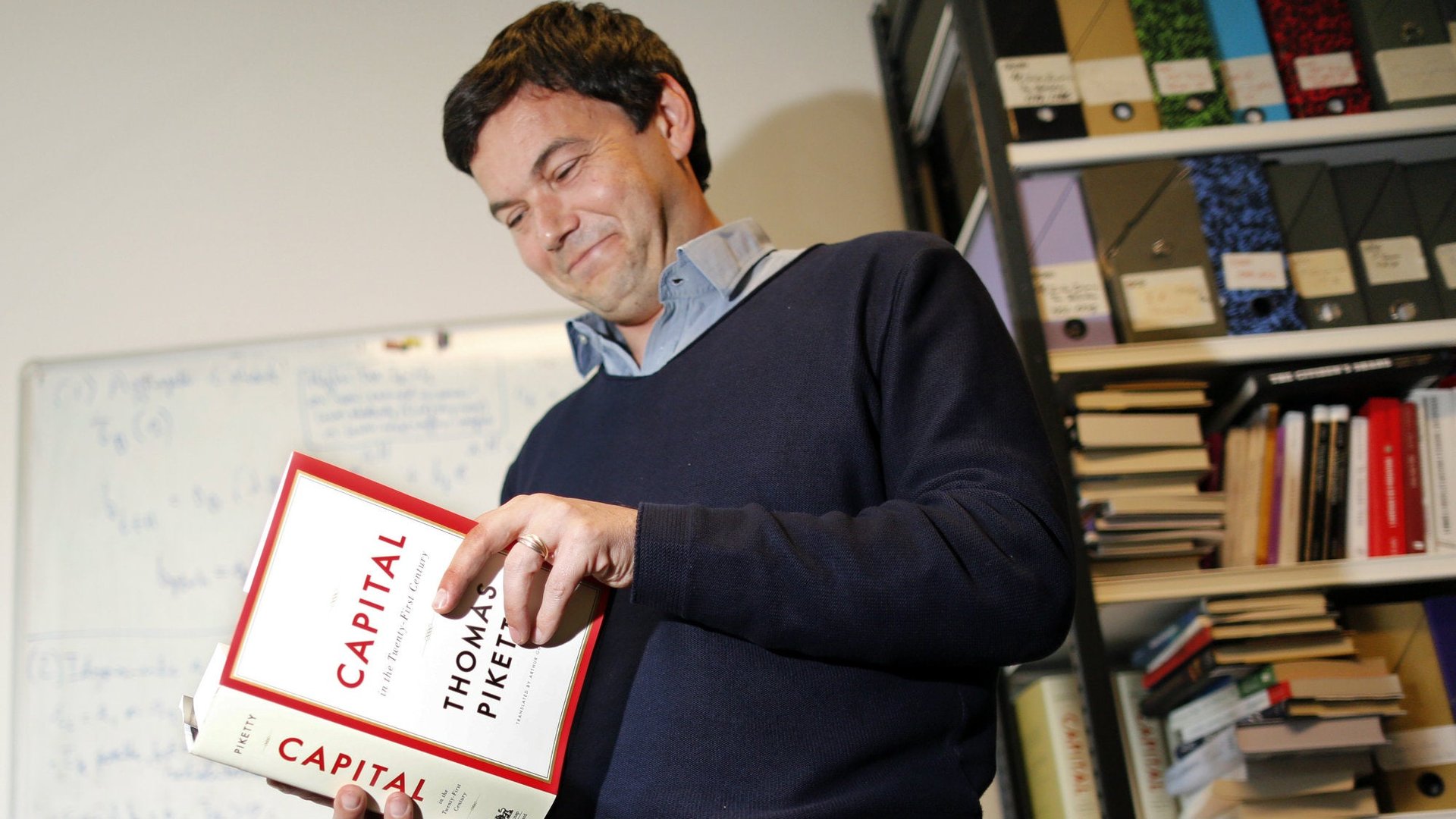

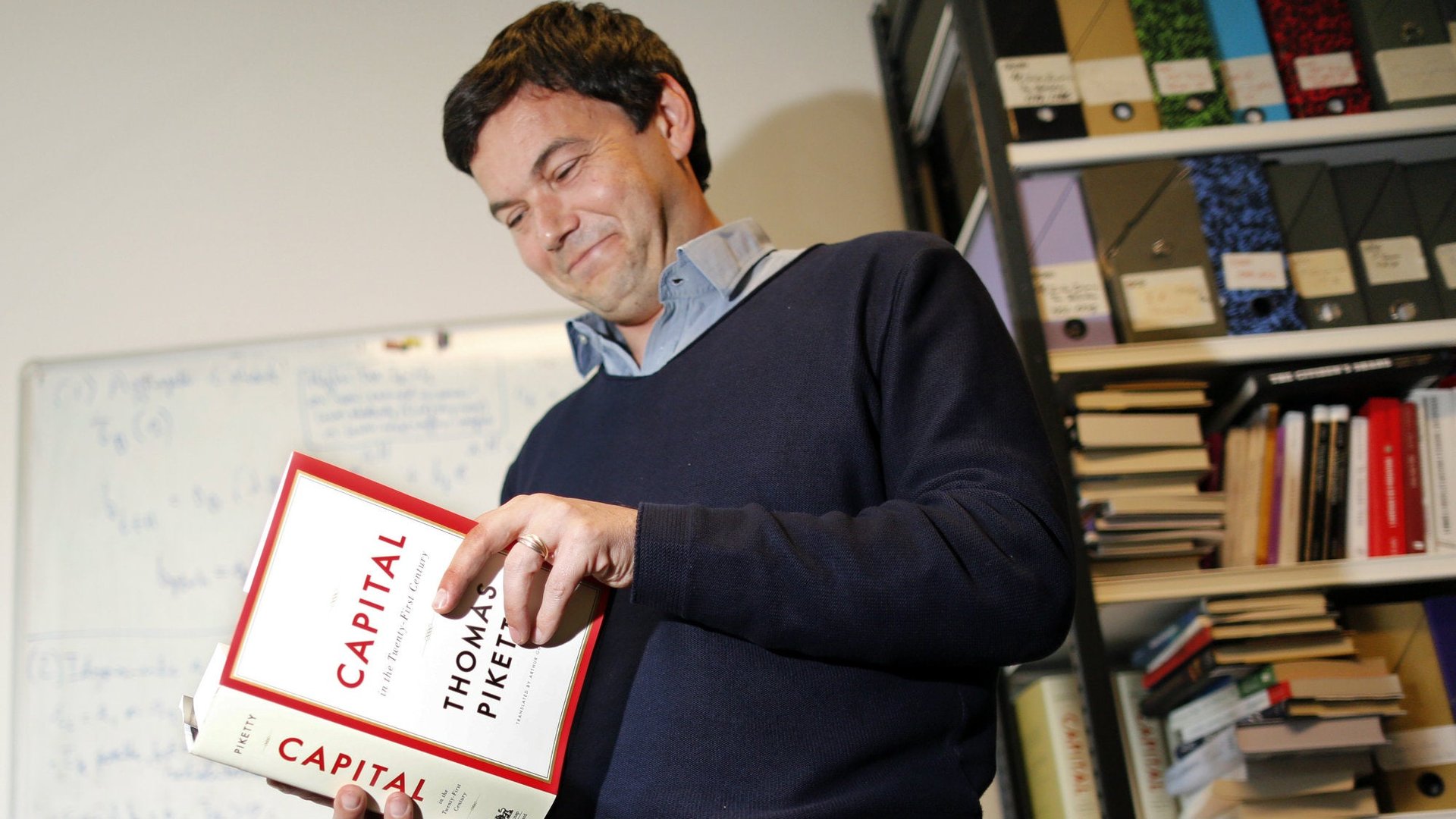

Thomas Piketty has been given the chance to craft some actual policies

What do you do after you’ve been elected the as the most leftwing leader of Britain’s Labour Party in its 115-year history and everyone is criticizing your economic policies? You form a council of international experts to boost your case. That’s what Jeremy Corbyn has done—and he’s assembled quite a group of experts.

What do you do after you’ve been elected the as the most leftwing leader of Britain’s Labour Party in its 115-year history and everyone is criticizing your economic policies? You form a council of international experts to boost your case. That’s what Jeremy Corbyn has done—and he’s assembled quite a group of experts.

Corbyn and his new shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, have appointed a panel that will meet once every three months to “discuss and develop policy ideas.” The group includes heavy-hitters like Thomas Piketty, Joseph Stiglitz, and Mariana Mazzucato. All are highly respected economists, and none defend the orthodoxy that has led EU and IMF officials to force Europe’s weakest, most heavily-indebted countries to cut spending since the start of the debt crisis in 2010. That makes sense for a Labour Party that declared itself “unashamedly anti-austerity” to great cheers from supporters at the party’s annual conference over the weekend.

Who are these people? Piketty, the French economist, achieved unlikely fame with his recent treatise on wealth inequality, Capital in the 21st Century. Ever since, he has been proselytizing as the rarest of creatures—the celebrity economist. Piketty hasn’t won many followers in his native France, where he feuds with unpopular socialist president François Hollande, but his dire warnings about economic inequality have won more interest in the UK and the US.

Mazzucato believes the government plays a big role in creating wealth by promoting innovation, and she is not shy about expressing her opinions (paywall). “I get all these hugs from civil servants because they are depressed,” the Italian-born economist told the Financial Times. “I walk in as an economist and I walk out as a life coach.”

Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize winner, is a longtime critic of inequality and Europe’s austerity policies. Having served on Bill Clinton’s market-oriented administration in the 1990s, this is the American’s second attempt to back an insurgent leftist party in Europe—earlier this year, he praised Greece’s far-left, anti-austerity Syriza government, saying “few finance ministers have such a talent for economics as Yanis Varoufakis.”

Varoufakis was later deposed as finance minister, a compromised Syriza accepted even more European-prompted austerity, and won another election. Labour’s McDonnell will hope things turn out slightly better for him—though he’d probably take the election victory.

Second opinions

This isn’t the first time a radical British politician has turned to outsider economists to bolster the case for bold new policies. Margaret Thatcher, Corbyn’s ideological opposite, turned to the work of libertarian economists Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman to support her policies. At the time, their views were considered radical. But nowadays, Hayek and Friedman’s policies are part of daily politics.

It will still be interesting to see what, if anything, Corbyn’s new council comes up with as an alternative to the status quo as Labour launches its bid for power in 2020.

The BBC’s Robert Peston suggests that, far from creating more radical policies, Labour’s new economic council will actually temper them. He suggests the ”quintessence of Corbynomics” is dead, as these economists would never sign off on the idea of “People’s Quantitative Easing,” or forcing the central bank to buy bonds issued by a state investment bank to fund infrastructure projects.

And what will they make of other policies created without their input, such as the so-called “Robin Hood” tax on stock market trades and the scrapping the Bank of England’s independence? The latter was introduced by a Labour government in 1997 to much praise from economists at the time.