In recent months, as the rancorous debate over refugees in Europe has grown louder, the silence in Asia has become increasingly conspicuous. What is Asia doing to help during the biggest refugee situation crisis since World War II?

For too long, the answer has been nothing. Officials and communities in Asia continue to act as if this is somebody else’s problem. The Rohingya people fleeing Myanmar are not their concern, they seem to say, much less the Syrians, Afghans and Somalis in the Mediterranean. Let Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon and those Europeans deal with the refugees, and we’ll just focus on our GDP.

This stands in stark contrast to what’s happening in Europe, where the incoming arrivals are much harder to ignore. From the crowd-filled square in Szeged, Hungary, to the overflowing train station in Munich, Germany, to Espace Léopold in Brussels, Belgium, pensioners, bureaucrats and Eurocrats have been arguing over the plight of the refugees for months. It’s a conversation fraught with irreconcilable differences, but a conversation nonetheless—like the one that led European leaders in September to draft a plan pledging to relocate 120,000 refugees and contribute €1 billion in aid.

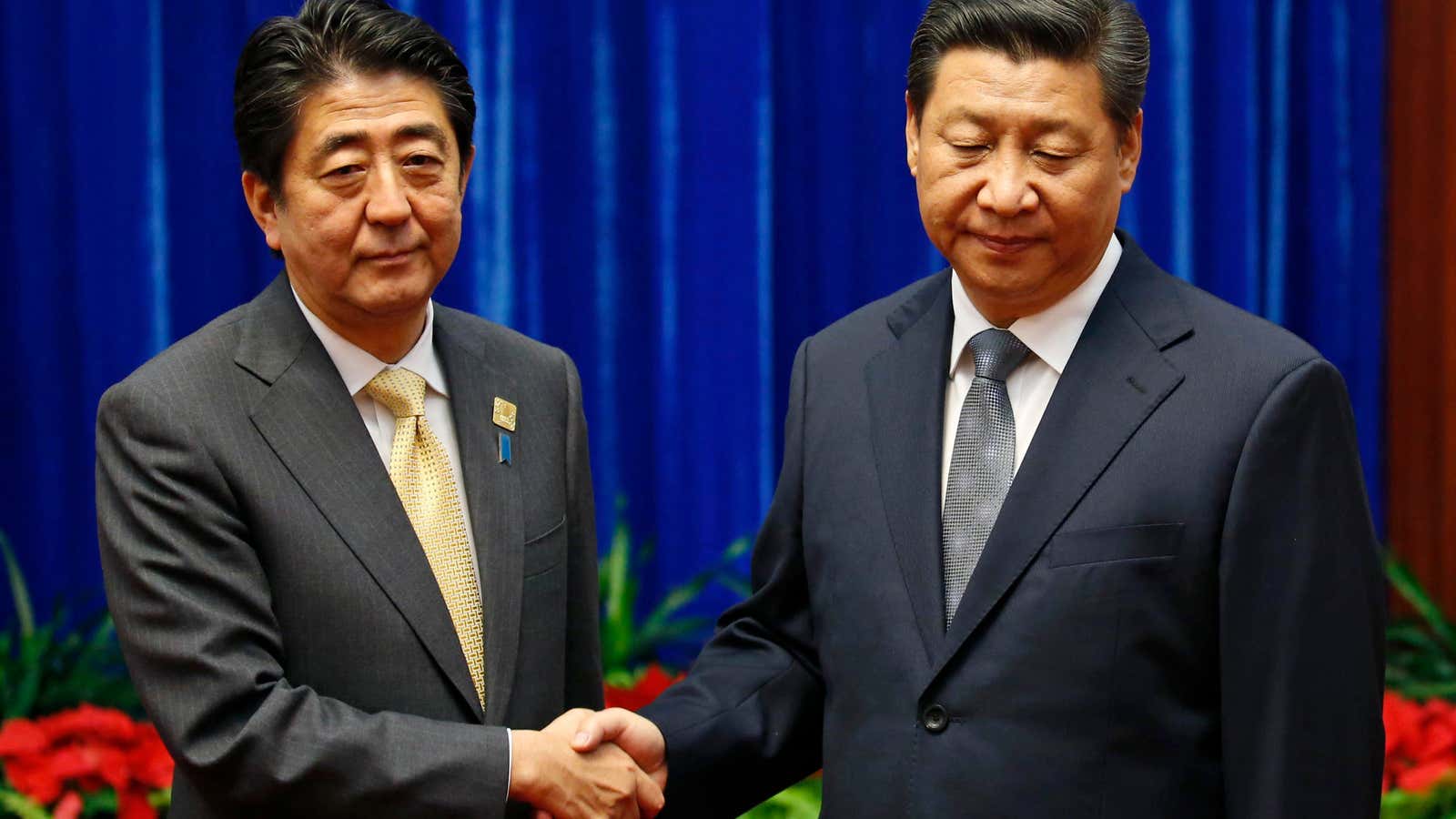

Thankfully, attitudes in Asia might be shifting somewhat. On Sep. 28, Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe told the UN his country would provide aid for Syrian and Iraqi refugees totaling $810 million

To be sure, Japan has a better track record than many of its peers when it comes to international aid. In 2013, the country ranked second behind the United States in terms of contributions to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, with $253 million in contributions. (That figure dropped to $182 million last year.)

In another positive sign, South Korea announced it would be creating a pilot resettlement program. The small but relatively well-off nation of 50 million people also tripled its financial support last year to $15.9 million. (The UNHCR has a budget of $5.3 billion.)

This is a start, but Asian states, particularly rich ones with aging populations and stable governments like South Korea, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong, need to do much, much more.

So far, a lot of this reluctance has been tied to an idea—commonly held among Asians—that the continent is full to capacity. But is it? Sure, Singapore and Hong Kong came in third and fourth in population density in 2014, but they, like Japan and South Korea, are home to aging societies that economists worry could hinder further growth. Indeed, Singapore has warned its working population will contract by 2020. Meanwhile the Japanese cabinet has already proposed measures to deal with its aging crisis, including new pension policies, and the proportion of citizens aged over 65 in South Korea has hit a historical high.

There also remains an Asian-centric tendency to think that asylum is a concept manufactured by the West, for the West. Today, half of the countries in East and Southeast Asia have not signed the Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol.

In terms of accepting refugees, there is still a lot of work to do. Last year, Japan granted just 11 asylum seekers protection. In Hong Kong,only 12 applications have been approved since a new vetting system started in March 2014. In 2013, the latest year for which the relevant UNHCR statistics (table 9) are available, 265 people were granted protection in South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. To put that into perspective, that’s 0.017% of the number of refugees hosted by Turkey, and 1.32% of the number Germany offered protection in 2013. These Asian states made decisions in 5,674 cases in 2013—roughly 0.07% the number in Germany the same year.

Of course, geography is a factor here. Barriers of both land and sea prevent asylum seekers leaving many of the primary conflict zones from traveling to East Asia. But this is only a small part of the problem—much more significant is the process by which countries assess asylum claims.

What Asian countries must do now is get off the sidelines. They need to develop and improve mechanisms for accepting and accommodating asylum seekers, and those that haven’t should immediately sign the Refugee Convention. They must change the ways they provide for asylum seekers who do arrive at their borders, appropriating food, housing, medical attention and counseling as needed. And lastly, they should increase individual contributions to the UNHCR.

Economists and aid workers agree the refugee crisis is not over yet, not by a long shot. While social media campaigns and activism has finally prompted some global movement, Asia’s leaders should not be fooled by the (still pretty sluggish) work going on in Europe. Whether they want to admit it or not, this migrant crisis is their problem, too.