Australia’s economy is softening, but stock market investors don’t seem to have noticed

Due to booming Chinese demand, Australia’s resources industry has had a bonzer few years. Heavy investment in new iron ore and coal mines created a labor shortage which meant miners have been earning more than bankers. This new class of wealthy “fluoro-collar workers” (named for their fluorescent safety jackets) has provided huge support to the housing market. Some of the nation’s most expensive homes are to be found in back-of-beyond mining towns such as Port Headland in the northwest, which Time magazine described in 2011 as as “isolated hamlet”.

Due to booming Chinese demand, Australia’s resources industry has had a bonzer few years. Heavy investment in new iron ore and coal mines created a labor shortage which meant miners have been earning more than bankers. This new class of wealthy “fluoro-collar workers” (named for their fluorescent safety jackets) has provided huge support to the housing market. Some of the nation’s most expensive homes are to be found in back-of-beyond mining towns such as Port Headland in the northwest, which Time magazine described in 2011 as as “isolated hamlet”.

It could all be about to end. As China’s growth has slowed, global commodities demand may have peaked. In its latest policy statement, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the central bank, has said (pdf, p. 64) that the economy will expand at just 2.5% this year, compared with 3.5% in 2012. The bank forecasts an end to the mining investment boom because the world’s diggers got overexcited about China in the boom years and dug too many new pits. Or, in bank language, ”The large amount of investment in the resource sector currently underway globally is likely to lead supply of bulk commodities to increase faster than demand.”

And that is bad news for Australia because, as the RBA points out, there is not much else going on in the economy. “There is little sign of a near-term pick-up in non-mining business investment.”

Meanwhile, the Oz construction industry is in a slump. The nation’s unemployment rate, at 5.4%, in January, was steady on the previous month. But a significant proportion of people have given up looking for work. These could well be cashed-up ex-miners who are taking time out to spend more time with their surfboards. The RBA’s statement notes that, over the second half of last year, employment in mining declined (it does not say by how much).

The bulls stampede onwards

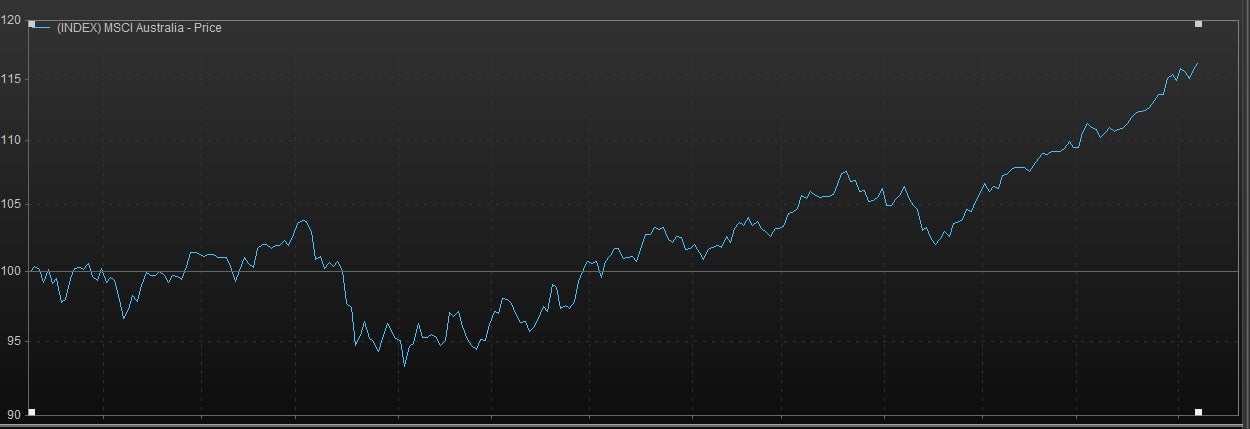

Funnily enough, though investors in the Aussie stock market have failed to notice the problems. Shares of the largest Australian companies have soared for much of the past year.

And as this chart shows, while the performance of Australian stocks (yellow line) has mirrored commodities prices (blue line) for much of the past five years, that link has broken, with equities steady or rising through the recent commodity crash.

Equities are doing well because investors believe the central bank can drive the nation through the downturn with interest rate cuts. The benchmark rate has fallen from 4.5% a year ago to 3%. And lackluster economic data seemingly serve only to convince people that more cuts are likely.

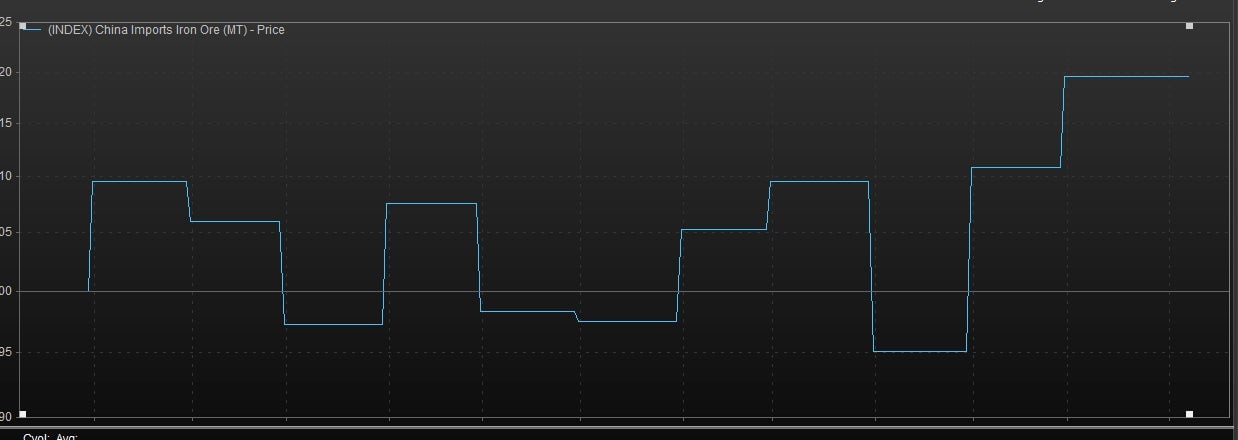

That is boosting retail stocks. Meanwhile, mining investors are happy because China’s iron ore imports have risen in recent months.

The iron imports are up because Beijing government has approved a raft of new infrastructure projects to stimulate the economy, while Chinese house-builders are building frenetically because they are finding it easy to get funding from the bond market and off-balance-sheet lending vehicles that are being heavily promoted by the nation’s banks.

But Australian investors are probably being a little too cheerful. China’s recovery is underpinned by a worrying credit boom. And Australia lacks ideas to wean its economy off China and resources. Its households are highly indebted and badly prepared for slowing economic growth. The sunny Aussie outlook makes a certain sense in a country that has not had a recession since the early 1990s—but even so, a little less optimism might be prudent.