Our team from Harvard’s School of Public Health arrived at the Kumbh Mela this week with a simple goal. Deploy an electronic record system to help health clinics record and collate complaints so that they can be tracked over time. The reason for this is obvious: If there is an exponential spike in diarrhea (to pick a particularly concerning contingency), officials could be looking down the barrel of a cholera outbreak. As it stands at the Kumbh—and in much of India—such a warning sign would come anecdotally, and only after hundreds had fallen ill.

The health facilities at the Kumbh, a festival believed to be the largest human gathering in history, itself are impressive by local standards. They’re clean, well stocked and staffed 24/7 by rotating physicians. According to Dhruv Kazi, a cardiologist and healthcare economist on our team who was born in Bombay, this is good representation of what the Indian government can accomplish when it so desires. This is, after all, a health care system serving 30 million. It was set up in just two months and will disappear by the end of March.

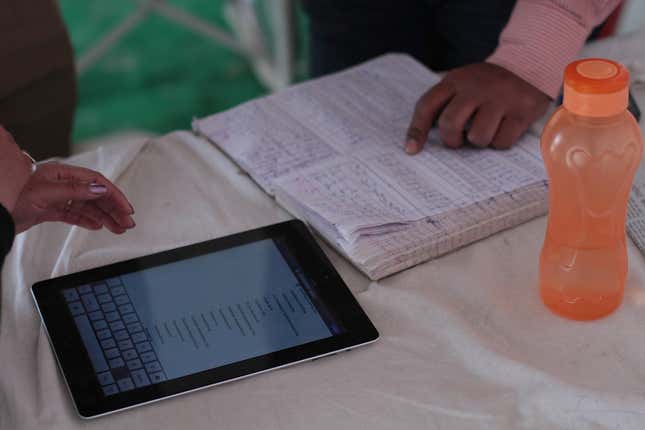

Yet while the facilities may be well appointed, health records are nearly non-existent. As our team observed, after a one-glance patient encounter, the doctor quickly scrawls down age, sex and a chief complaint. These notes are mostly illegible, largely incomplete and essentially useless. It’s forgivable given the strain on each doctor; each clinic sees around 700 patients a day. (To put that volume in perspective, the bustling emergency department at Manhattan’s Weill Cornell Hospital sees about 200 patients a day.)

Harvard’s team created a simple iPad-based electronic medical record that tracks chief complaints and prescriptions and then deployed an enthusiastic team of Indian medical students and interns to gather the data from four clinics each day. The iPads were linked to a web-based portal that synced and collated the data, ran simple analytics, and provided real-time results.

The building blocks—a few iPads and a web-based application—are elegantly simple, and the manpower manageable. But thanks to the proliferation of internet connectivity across India, these tools could allow rural clinics to “leapfrog” from handwritten charts to a portable, web-based system accessible on any mobile device. This would give previously unconnected clinics the benefits of real-time syndromic surveillance without the burden of a resource-intensive electronic health record system, something American physicians have struggled under for years.

So far the Harvard team has gathered more than 15,000 patient records, an impressive number by any research standards, and arguably the largest public health dataset ever gathered on a transient population. Their findings have been stable and predictable; most complaints are of cough and cold, and most prescriptions are for anti-inflammatories drugs, like ibuprofen. That’s good news to everyone’s ears as millions of new pilgrims enter Allahabad in preparation for February 10, the holiest bathing day on the calendar.

We welcome your comments at ideas@qz.com.