At the LEGO Future Lab in Denmark, designer Carlos Arturo Torres Tovar saw the wildest creations during his internship. There was a fully functioning automobile made with LEGO bricks and a LEGO robot that solved Rubik’s cube puzzles. He also saw people who had built arms and legs for themselves using LEGOs.

He immediately thought of his home country, Colombia. “My generation was born in the armed conflict that has already been in the picture for 50 years.” At that moment, Tovar knew what he wanted to do for his master’s thesis project: He was going to build a prosthetic for children using LEGO.

Since the 10th century BC, prosthetics have had two goals for people with limb differences: increasing the ability to function as well as looking more “normal.” However, some high-tech prosthetics allow users to accomplish more than just everyday tasks, they allow patients to run in races and even climb mountains. But the social and emotional facets of using prosthetic limbs are seldom part of the design.

Tovar hopes to turn his coursework at the Umeå Institute of Design in Sweden into a commercially viable prosthetic arm made mostly of LEGO bricks and pieces. He estimates the price of IKO Creative Prosthetics System will be about $5,000 with only the recurring fee to be the $1,500-3d printed socket that will need to be replaced yearly for growing children. While cost comparisons are hard to nail down, a 2012 study in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation noted that myoelectric upper limb prosthetics could range from $40,000 to $100,000. Another study also showed that for some adults who use prosthetics, the lifetime cost projections can total over $800,000.

With the high cost in mind, Tovar wanted to empower children to be part of the creation of their new limb. Here’s how Tovar came to develop a prosthetic arm with the help of a child from his native Colombia.

An idea is born

Two years ago, a video of a woman who had built herself a leg using LEGO surfaced on the internet. Tovar watched that video and was fascinated. He knew that the leg was not functional but he remembered what his psychologist friends said of children with limb loss in Colombia. Simply put, the social and emotional challenges up against them weren’t being addressed by their prosthetics. “Looking normal” is rarely ever achieved with prosthetics. However, after watching the videos like that of the woman with her LEGO leg, Tovar became more convinced that he had to design a prosthetic using LEGO because the bricks were social. “When you assemble a LEGO set, you assemble it with your parents or your friends or you even make new friends with them,” said Tovar.

Tovar decided that he would find a candidate for his prosthetic in his native country of Colombia, where 5,400 kids lose their limbs due to the violence of the armed conflict or in accidents every year. Colombia is the 2nd most dangerous country the world when it comes to land mines. Tovar insisted that he do the research in Colombia because at LEGO he learned much about working with children.

“With anything having to do with kids, you really need to speak the language well because you need to connect with them right away,” he said. “With kids, you may have just one or two chances to be friends with them.”

Should children be able to design their own prosthetics?

As Tovar didn’t have a background in medicine, he sought the help of CIREC, an organization in Colombia that he described as understanding the huge process of providing a child with prosthetics. They matched Tovar with a child who would be trying the prototype, Dario, then 8-years-old, who was born with only a partially developed right arm that stopped growing at the elbow. He was delighted to see Dario’s drawings of robots and drivers with robotic eyes that “knows exactly what he needs.” This reconfirmed Carlos’ idea for the project because he wanted the children to be able to build their own prosthetics.

After flying back to Billund, Denmark, Tovar’s project was met with approval. “They [LEGO] validated the idea that kids should be the drivers of their own experience and be in control of everything.” Then Soren Holm, the head of the Future Lab, told Tovar to go to the brick library and fill his large suitcase with as many bricks as he could carry. He only had two hours before his flight left for Sweden. “It was a crazy moment.” he said. “I had access to every brick in the world.” That day, Tovar filled his suitcase with 8,000 bricks and placed them in plastic bags to keep them organized and sorted.

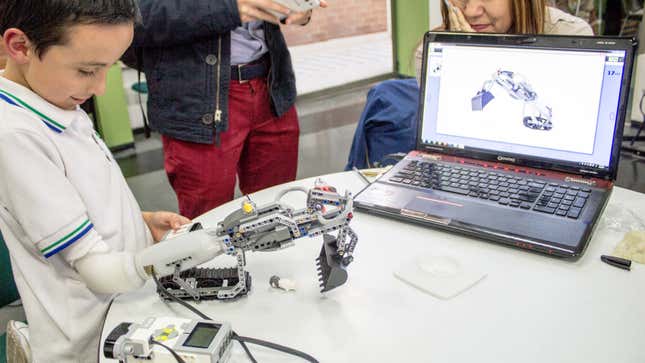

At Umeå, Tovar managed to create a prototype using LEGO Mindstorms, a robotics computing platform, 3D printed materials, and of course, LEGO bricks. He then raced back to Colombia for the first prototype trials. As with many prototype trials, there had to be protocols set in advance to make sure it was meeting the goals of the design. With his newly created IKO that would be modular in design with only one fitted unit, the socket that will need to be replaced yearly as a child grows. This would save on costs. Studies show lifetime projection costs for prosthetics for patients who have lost their limbs as adults to number into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Play redefines what a prosthetic is for kids

With any design, it must be tested. Tovar began to assess several critical factors, the first of which was if the patient could build his own prosthetic as he only had one hand. Clearly, the child would not only need to ask for help but he would also have to remain patient. Fortunately, Dario managed to lead his family and the staff at CIREC through the building process of a very complicated battery-powered remote controlled backhoe. The inclusive nature of the building process left everyone feeling proud.

Experts agree that building your own prosthetics could provide a tremendous benefit to kids.

“I think for a child, it would be incredibly empowering.” said George Gondo, Director of Research and Grants at the Amputee Coalition, a national advocacy organization for persons with limb loss. “Here’s something that they can actively manipulate to make it do the types of things that they want to do.”

Tovar also tested to see if Dario could play with typically developing children with the IKO arm. Dario’s best friend who does not have limb differences, was brought to hospital and the two were left alone to play. Prior to seeing the arm, Dario’s friend had shared feelings of sorrow for him because Dario had only one hand. However, after playing with Dario with his new arm, the child approached Tovar and said, “I want one of those.”

Kids are ready for these LEGO arms but are we?

The two children had fun playing together but at one point, Dario’s friend retreated to solitary play only to return and avidly seek compliments for the spaceship that he just built. It was obvious that he was jealous. Tovar suggested that the friend could put his spaceship on Dario’s new arm and then the two had a blast. The revelation that came afterwards was incredible for Tovar who had planned for the arm to fulfill social and emotional needs but did not plan for the arm to become a learning tool for a patient’s peers so they could begin to understand what it was like to live with limb differences.

Oddly enough, all of this was achieved through LEGO’s main purpose of existence: play—an activity that is constantly being deleted out of children’s schedules everywhere, especially at school. As the arm was made of LEGO components, Dario’s friend immediately imagined what it was like to have such an arm. The familiar nature of LEGO had given them that chance. What was even better was how play resolved the discord between the two as his friend had become jealous.

It broke Tovar’s heart to have to take the arm away and bring it back to Sweden so that he could complete his project. However, in December of this year, Dario and nine other children in Colombia will be receiving new and improved prototypes of the IKO Creative Prosthetic System. Tovar is currently working with engineers and investors to make the system work myoelectrically so that remote controls are not necessary but rather thought-triggered by sensors.

Perhaps the greatest gain from Tovar’s design is the complete image makeover of what wearing a prosthetic will mean to a child when he chooses the IKO. It stands to change not just how a child with a limb difference will feel about himself but on a broader scale—the IKO may possibly change how we see these high-tech prosthetics today.

Or perhaps we’ll see that the only real superpower that these prosthetics have is not to make someone superhuman, but rather it’s to make all of us a bit more humane.