A month ago, Uday Prakash sparked a literary revolt.

On Sept. 4, the Indian author returned a Sahitya Akademi award for his book, Mohandas. The Sahitya Akademi, or National Academy of Letters, is India’s premier literary institution that honours Indian authors for writings in more than two dozen languages.

Prakash, who writes in Hindi, was protesting against the murder of MM Kalburgi—a 77-year-old rationalist scholar and a Sahitya Akademi award winner—by unidentified gunmen at his residence in Karnataka in August. “There was a threat to my father from groups that couldn’t digest his views on caste and communalism,” Kalburgi’s daughter told the Hindustan Times newspaper after the incident.

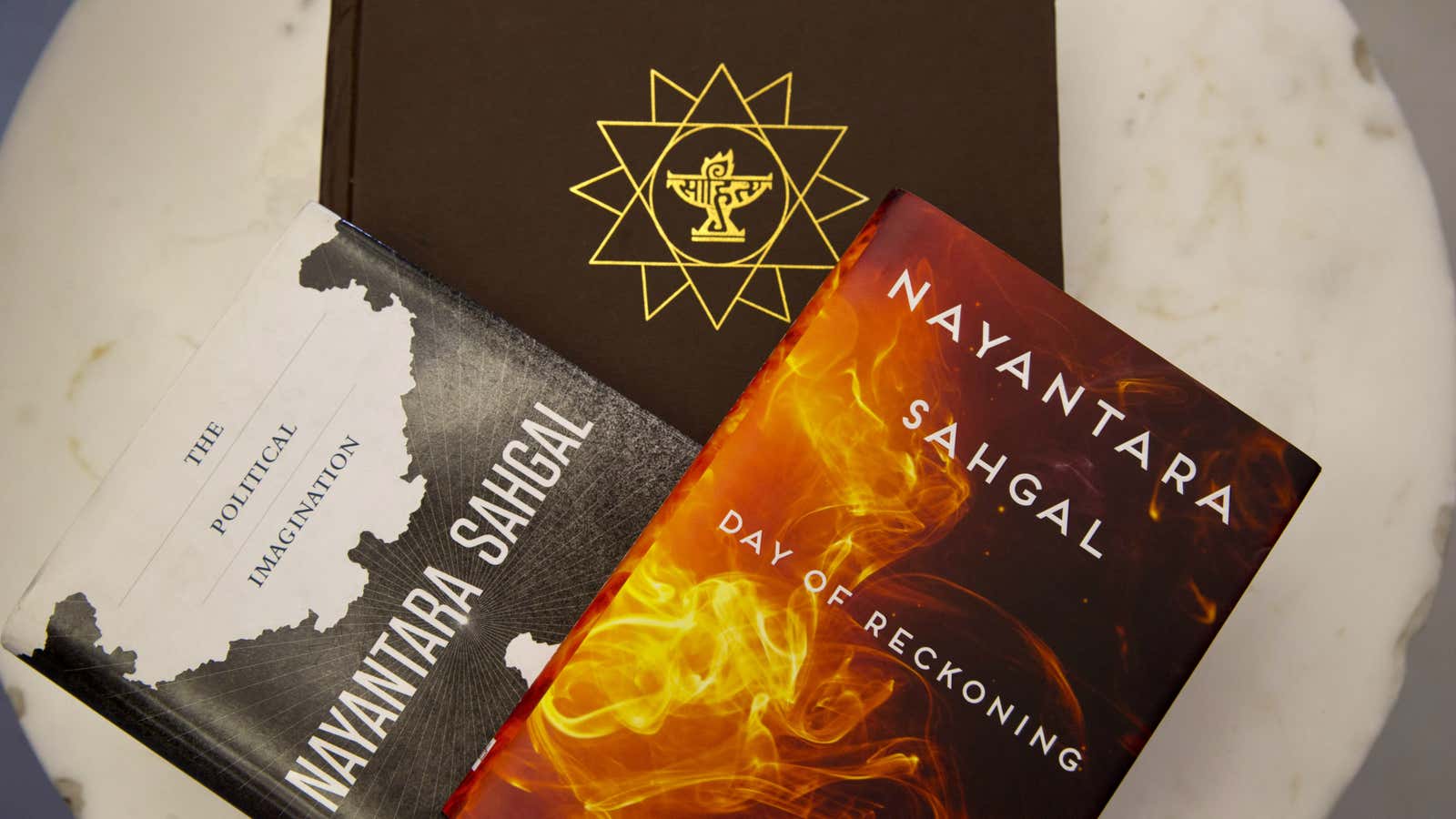

On Oct. 6, Nayantara Sahgal, an Indian author who had won the Sahitya Akademi award for her novel Rich Like Us in 1986, also returned the prize. Incidentally, Sahgal is the niece of India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who established the Akademi in 1954.

“Rationalists who question superstition, anyone who questions any aspect of the ugly and dangerous distortion of Hinduism known as Hindutva—whether in the intellectual or artistic sphere, or whether in terms of food habits and lifestyle—are being marginalized, persecuted, or murdered,” she wrote in a statement.

Sahgal said that she took the decision after a 52-year-old Muslim man was killed by a mob in Dadri, in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, in September, for allegedly consuming beef. The incident effectively released the literary fraternity’s resentment against the growing intolerance within India, and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government’s inaction to protect basic freedoms.

Sahgal further explained:

The prime minister remains silent about this reign of terror. We must assume he dare not alienate evil-doers who support his ideology. It is a matter of sorrow that the Sahitya Akademi remains silent. The Akademis were set up as guardians of the creative imagination, and promoters of its finest products in art and literature, music and theatre.

Since then, more than 40 authors, poets and playwrights have returned the honour. From Ashok Vajpeyi (Kahin Nahin Wahin), Ghulam Nabi Khayal (Gashik Minaar), and Aman Sethi (A Free Man) to Sarah Joseph (Aalahayude Penmakkal), Surjit Patar (Haneray Vich Sulgadi Varnmala) and veteran writer Krishna Sobti, India’s literary fraternity is speaking out in increasing numbers.

The unprecedented wave of awardees returning their prize has found support from a number of India-born writers including Salman Rushdie. The author of Midnight’s Children and The Satanic Verses, Rushdie tweeted: “I support Nayantara Sahgal and many other writers protesting to the Sahitya Akademi. Alarming times for free expression in India.”

However, in an interview with the Indian Express newspaper, Amitav Ghosh, another well-known author, said that the anger should be directed at the current leadership of Sahitya Akademi, and not at the institution per se. He would not be returning his award, he clarified.

“I received my Sahitya Akademi award 25 years ago, in 1990. At that time, the institution was held in general respect by writers,” Ghosh said, whose notable books include The Glass Palace and Sea of Poppies.

“There can be no doubt that the present government is tacitly enabling these attacks by failing to take punitive and preventive action. In refusing to protest, the Sahitya Akademi is shamefully in dereliction of its duties,” Ghosh said.

Meanwhile, 80-year-old novelist Dalip Kaur Tiwana announced her decision to return her Padma Shri, one of the highest Indian recognitions. “…This is my way of protest. Minorities are being crushed and writers and rationalists are being murdered, and no one is allowed to speak,” Tiwana told the Indian Express on Oct. 14.

So far, the Sahitya Akademi is unsure about what to do.

“We are facing an unprecedented situation,” Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, president of the Sahitya Akademi, told the Business Standard newspaper, on Oct. 13. “At present, we do not know how to respond to those wanting to give back their awards. So, it was decided that a meeting of the executive council would be called.”

The executive council, which comprises government nominees, officials and a representative of over two dozen languages, will meet on Oct. 23.

The Narendra Modi government has remained silent on the matter, except for a reaction from Arun Jaitley, India’s finance and information and broadcasting minister, who in a Facebook post on Oct. 14 said:

“Nobody has alleged any governmental complacency in these crimes. But to manufacture a revolt, it is necessary to obfuscate the truth and create the impression that the Modi Government is responsible for these crimes even if, they took place in the Congress and Samajwadi Party ruled States… There is no atmosphere of intolerance in the country. The manufactured revolt is a case of an ideological intolerance towards the BJP.”

Manufactured, or not, this revolt isn’t fictional.