The European Union aimed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 20%, by the year 2020, and it announced this week that it has already exceeded that ambition, with a 23% cut.

No other region of the world has been pursuing goals to mitigate climate change so seriously or for so long, and for that the EU should be commended. But the fact that it’s already hit the greenhouse gas target is an indication that Europe should have set the bar higher.

Individual member states have their own internal targets, but Europe as a whole has three climate targets: a 20% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions; 20% of energy produced from renewables; and 20% less energy used, all by 2020.

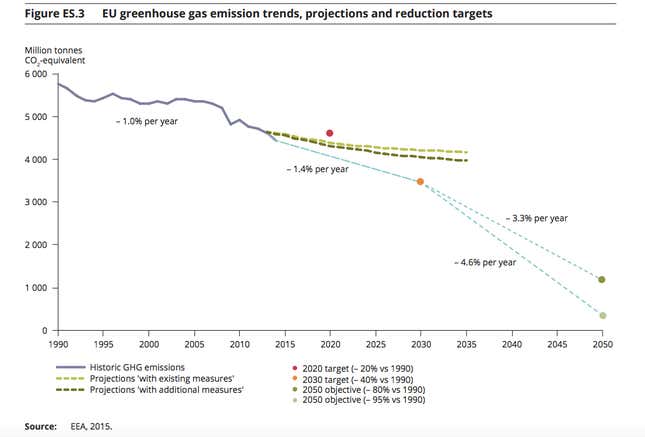

That sounds ambitious, but was it? The base year chosen by the goal-setters in 2007 was 1990, and much of the reduction was already in the bag when they started the project. This makes sense, in terms of projecting a likely trend of reduction; but it also lightened the load in terms of how ambitious reductions needed to be, setting it at just 1% a year.

With hindsight, we know that Europe could have set a higher goal and still achieved it. So why weren’t the targets higher? Back in 2007, a 30% target in the same timeframe was discussed. Wrangling between national governments about which European countries should bear more of the burden was one limiting factor. Domestic politics, and the difficulty of selling legally binding targets to voters, didn’t help.

Yet another problem was the rest of the world. Other industrialized nations and huge emitters like the US and China wouldn’t sign up to binding targets at that time, making it harder for Europe to sell the idea of going it alone to its citizens. And while there has since been progress on those fronts, the goals are even lighter, and less binding, than those in Europe.

Future targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are much more ambitious: 40% by 2030 (from 1990 levels), and 80% by 2050. And the region won’t get there easily: “Although the EU is expected to achieve its 2020 targets, current efforts need to be stepped up if it is to meet these more ambitious longer-term objectives,” noted the European Environment Agency in a report this week.

In this phase, meanwhile, efforts of the member states will be even more important. Europe’s reductions in emissions between 2007 and now were helped by something the goal-settings didn’t foresee: the financial crisis.

Emissions fell after 2008 in part because productivity fell, after industry was sideswiped by faltering funding and markets. (Moreover, the measured reductions in emissions include some accounting practices, including counting the burning of wood as carbon neutral, which some consider dubious).

But economic growth is now possible without increases in greenhouse gas emissions, the International Energy Agency said this year. That means reductions should be possible even without another crisis.

Europe is also on course to meet its aims to produce a fifth of its energy from renewable sources by 2020 (some countries have already exceeded that, too), and reduce energy consumption by as much.

The achievement so far shows that setting goals does work as a strategy to reduce emissions and increase efficiency and energy from renewables. At the United Nations Conference on Climate Change, to be held in Paris in November, the question will once again be how far global ambition will stretch to set targets that actually mean something.