This post has been updated.

Monetary policy isn’t reality television.

This is a subtle point. But amid growing clamor for the Federal Reserve to do something—anything!—it’s important to note that what the Fed does is incredibly important not only for its US constituency but also for the world economy. Mistakes can be costly.

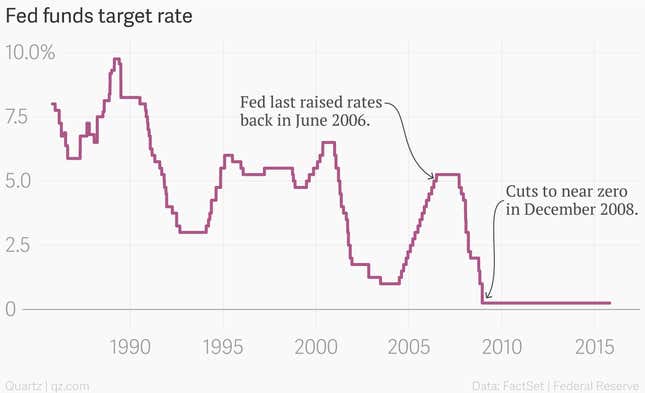

That said, where are we? Well, the same place we’ve been since late 2008: Zilchville. The Federal Open Market Committee kept interest rates unchanged in its latest decision today, but it did use unusually specific language when discussing the possibility of coming interest rate hikes. The committee said it will watch progress in both the labor markets and price movements in “determining whether it will be appropriate to raise the target range at its next meeting.” That mention of the “next meeting” seemed to get some attention in the markets. Short-term interest rates rose as investors priced in a larger chance of a rate hike in December.

The Fed cut interest rates to zero during the Great Recession and then embarked on a range of unconventional monetary policies—laid out in detail by former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke in his recently published memoir—in an effort to first stabilize the economy and then support economic growth.

The economy has made significant progress since 2008. For example, unemployment has fallen to relatively normal levels after spiking during and after the financial crisis.

Some argue that with unemployment more-or-less normal, the Fed should start raising rates now. However, there are other measures of unemployment besides the traditional unemployment rate that show a lot more people could be put to work.

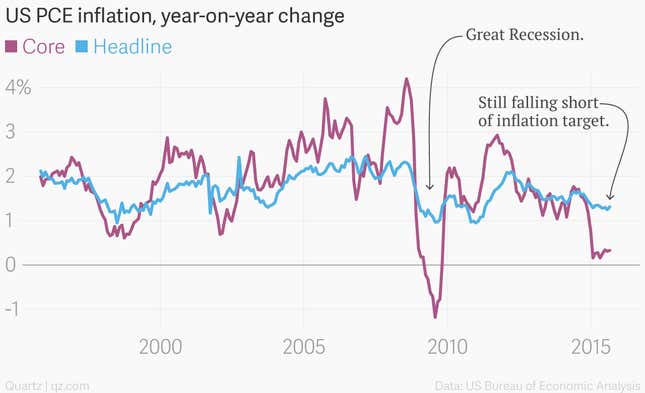

But even if unemployment was back to “normal,” the Fed’s job is more complicated than that. The US central bank has to worry about boosting employment and keeping prices stable. (In the world of central bankers, price stability essentially means a slow and steady rise in prices. The Fed’s target for inflation is 2%.)

Unfortunately, prices—the gauge the Fed likes to look at is known as the PCE price index—have persistently undershot the Fed’s 2% goal over the last year.

Part of that has to do with a collapse in oil prices globally. And so far it seems like the Fed pretty much thinks that in a few months, the sharp year-on-year decline in oil prices will fall out of the data and inflation rates will begin to move back toward its 2% target.

That could happen. And if that’s the case, it would be good for the Fed to get started on what some have humbly called the greatest monetary experiment of all time—raising interest rates using a bunch of untested tools.

However, if inflation is actually being pushed lower for a number of other reasons—such as a slumping China—raising interest rates now would risk slowing the US economy a bit too much and tipping the world’s biggest economy back toward disinflationary or even deflationary footing. That’s a big risk to take.