The Fed proposes to smother banks with capital, but not end “too big to fail”

When JP Morgan lost $6 billion on a bad derivatives bet in its “London Whale” fiasco last year, it wasn’t just unpleasant for the bank, but was also a blow to regulators’ credibility. Banks that don’t properly supervise their own traders are just the kind of thing that regulators—most particularly the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, according to a longtime investment banker—were supposed to be watching out for.

When JP Morgan lost $6 billion on a bad derivatives bet in its “London Whale” fiasco last year, it wasn’t just unpleasant for the bank, but was also a blow to regulators’ credibility. Banks that don’t properly supervise their own traders are just the kind of thing that regulators—most particularly the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, according to a longtime investment banker—were supposed to be watching out for.

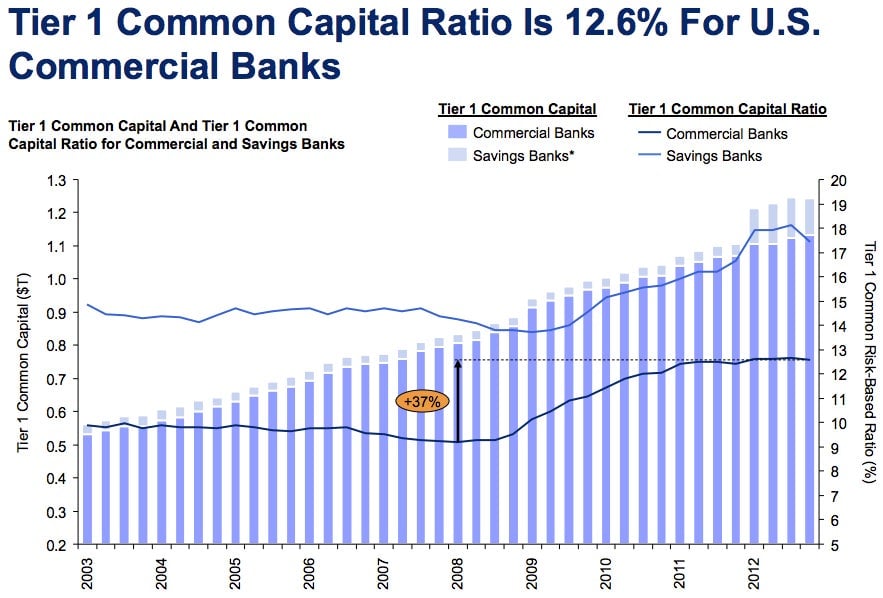

So the US Federal Reserve, tasked with making sure systemic risk doesn’t wreck the financial system, has been looking for ways to do it even when other agencies fall down on the job. Its solution: Smother banks with loads and loads of capital. In a speech today before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Fed governor Daniel Tarullo announced new proposals that, boiled down, force the nation’s smallest and largest banks to stockpile funds in case of a shock to the financial system. That way, if credit seizes up and banks can no longer borrow to refinance their debt or fund their daily operations, they’ll have plenty of capital on hand to hold off insolvency. Well, that’s the idea, anyway.

The proposals call for new premiums on banks with assets worth more than $50 billion; for premiums on systemically important banks considered “too big to fail” on an international basis (this includes a timely application of Basel III requirements, which would force JP Morgan, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank AG, and HSBC Holdings PLC to hold some 2.5% more high-quality capital); and for forcing banks that securitize products to retain a portion—recent proposals have said 5%—of the securities they’ve sponsored. This last piece would theoretically prevent banks from issuing securities in bets they know they will lose and then selling the whole lot off to suckers, as Goldman Sachs did when it issued credit-default swaps against subprime mortgages which it sold to AIG.

The new proposals would also standardize risk-weighting procedures—particularly for regional and community banks. These more stringent procedures would probably force them to (surprise) hold more capital.

Finally, the proposals would require banks to hold a minimum proportion of long-term debt (currently, they mostly hold short-term Treasurys of 2-3 years maturity). The idea here is to align the banks’ interests more closely with those of the economy as a whole—that if they hold unsecured long-term debt, they won’t bet against those markets fundamental to the functioning of the economy—the mortgage market, for instance.

Tarullo also cited concerns about a shadow banking system—and the regulation of financial institutions which are not banks, though there were no concrete proposals.

But it will save the banks?

The Fed’s proposals will make banks pay a penalty for being too big, and force them, in theory, to act more responsibly. But there could be unintended consequences.

First, more long-term debt could hobble the banks in a bad economy. Some banks already hold some debt with a longer duration—10 or even 30 years—purchased at low interest rates. If interest rates rise then those bonds lose value relative to the money they could or should be making. Those losses could be more acute in a sluggish economy where their other investments aren’t making them much money. This is already a concern: Christopher Wolfe, a managing director in Fitch’s financial institutions group, said long-term debt is one of the main things his team has been looking into lately to determine the credit-worthiness of the firms they cover. If the Fed forces banks to up their holdings, it could effectively be penalizing them for simply existing in a bad economy.

Second, it could discourage foreign banks from operating in the US. Under the current provisions of Dodd-Frank that Tarullo has promulgated, foreign banks will be forced to establish US holding companies. In these holding companies, they’ll be required to keep a certain amount of high-quality capital at all times, restricting their ability to move that cash overseas. That might make it simply too expensive for them to do business in the US, causing them to leave that business. For example, Barclays and Deutsche Bank have already given up their titles as US bank holding companies, allowing them to evade certain new capital requirements.

Third, it’s not clear that the reform will lead to smaller banks, or even that the Fed has that goal in mind. Nathan Sheets, Citigroup’s global head of international economics, who spent 18 years at the Federal Reserve, said last month at a conference, “I think the bank model over time is as robust as the capital markets model,” and argued that US banks were likely to expand over the next 10 years. In the same way banks in Europe are responsible for the vast majority of lending and thus have massive balance sheets, US banks—Sheets believes—could end up expanding the scope of their operations, with more hands in all pots.

Further, forcing small banks to hold onto more capital and spend lots of money on lawyers to fulfill new regulations makes them less viable, and encourages them to consolidate. That’s already begun to happen; many community banks have been allowed to fail since the financial crisis, and many states have cited the consolidation of their community banks as a growing trend. The end result is that big banks seem a likely outcome of all this regulation, albeit ones awash in capital.

The Fed’s desire that banks be rolling in cash doesn’t fix the financial system in the long term. It just cushions it against the risks that remain in place. It certainly doesn’t contribute to the separation, which the Volcker Rule is meant to achieve, of more bread-and-butter banking and lending from trading and investment banking. The capital-heavy model is likely to hold up for a while, but it’s a questionable antidote to future systemic financial crises.