Chinese president Xi Jinping just declared that China will grow an average of 6.5% a year from 2016 until 2020. The announcement comes as part of China’s 13th Five-Year Plan—that throwback to hoary socialist planning that lays out the country’s blueprint for economic and social development—in which Xi vows to, by the end of the decade, double China’s 2010 per capita GDP (link in Chinese).

That might sound like a downgrade given that the 2009-2015 target was 7%. But it’s not—it’s higher than the 6.2% average that the not-especially-pessimistic IMF expects.

More importantly, that 6.5% target is also a faster pace than China should be trying to grow, says Jiming Ha, an economist at Goldman Sachs in Hong Kong.

“Can China grow its economy by 6.5% in the next five years?” he says. “Maybe it can—but not without a cost.”

That tradeoff has to do with investment, debt, and household consumption. For the last decade or so, policies designed to spur investment-driven GDP growth shifted wealth from households to the state. That suppressed household consumption and forced up the savings rate. All those deposits sitting in state banks formed an ample pool of cheap capital, boosting investment all the more.

This recipe for easy GDP was also a recipe for wasteful investment. Spending on unneeded projects boosted GDP each year but created little future value. Shriveling returns on these investments have left Chinese companies with less profit to repay debt. As of the first quarter of 2015, they had racked up at least $16.7 trillion in debt, more than 160% of GDP.

Debt is now growing much faster than China’s economy is.

To slow this alarming pace, China must also let investment drop sharply, while allowing household consumption to rise. But since that will take time, growth must fall.

Conversely, to keep GDP rising at anywhere near Xi’s target, China can’t slow investment much at all. And that means debt will keep climbing to even more dangerous levels. For instance, economist Yu Yongding recently estimated that, without fundamental changes in China’s economic structure, by 2020, corporate debt will hit an ear-popping 200% of GDP (pdf, p.7).

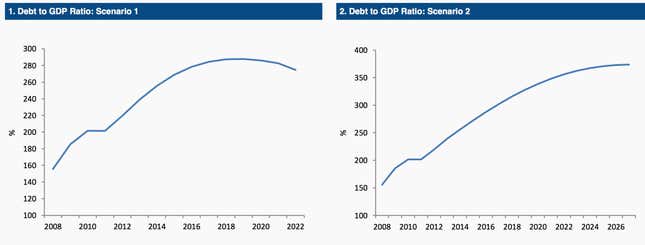

Goldman’s Ha analyzed what would happen to China’s debt if investment slowed at different rates (while holding consumption growth constant). The chart on the left shows what happens when investment falls more sharply, dragging down GDP. Meanwhile, the one one the right reflects the much more gradual decline in investment growth necessary to meet Xi’s 13th Five-Year Plan target (and falling thereafter so that growth averaged 5.8% from 2015 to 2027).

But wait—if China’s debt problem is already so severe, how come it’s dodged a crisis so far?

This brings us back to the country’s astronomically high savings rate. The swollen cache of deposits—on which banks have paid below-market rates—let Chinese companies endlessly refinance their debt.

The days of easy rollovers will soon be over, says Ha. China’s population is aging at a brisk clip, which will drag down the household savings rate. Rising wages will eat into profits, shrinking corporate savings. Weaker economic activity will generate less tax revenue, depressing the government’s savings rate.

In short, locking China in for 6.5% GDP growth for the next half-decade ups the risks of a financial crisis. While that sounds scary, for both China and the global economy, it might be preferable to the alternative. The longer the government lets its debt rise faster than its ability to pay, the longer everyone else must wait before Chinese consumers and businesses become genuine engines of global growth.