Human rights lawyers in China tell harrowing stories about their own torture and abuse

Beijing prosecutor and lawyer Tang Jitian was on the grounds of a Chinese black jail last year, investigating a case, when local police officers handcuffed and attacked him.

Beijing prosecutor and lawyer Tang Jitian was on the grounds of a Chinese black jail last year, investigating a case, when local police officers handcuffed and attacked him.

“I was first strapped to an iron chair, slapped in the face, kicked on my legs, and hit so hard over the head with a plastic bottle filled with water that I passed out,” Tang said to Amnesty International of his sudden detention. Three other lawyers with him received the same treatment that day.

Under the ever-tightening censorship policies of China’s central government, human rights activists and lawyers in the country have found themselves subject to a brutal, sweeping crackdown this year. On Nov. 12, human rights organization Amnesty International released a new report that tells Tang’s chilling story—as well as dozens of others from lawyers who’ve also been assaulted by the Chinese government.

These personal accounts come to light at a crucial time: Next week, China will answer questions from a United Nations anti-torture committee at a conference in Geneva—the UN’s fifth probe into the country’s torture practices.

Titled “No End In Sight,” Amnesty’s report features personal interviews with 37 lawyers, as well as an examination of several hundred court cases. The report’s bleak findings—which suggest abuse in China’s criminal justice system is rampant, systematic, and unfailingly violent—echo conclusions drawn by other non-profits in the past. Parties such as the US State Department and the American Bar Association have publicly voiced their concern about these revelations.

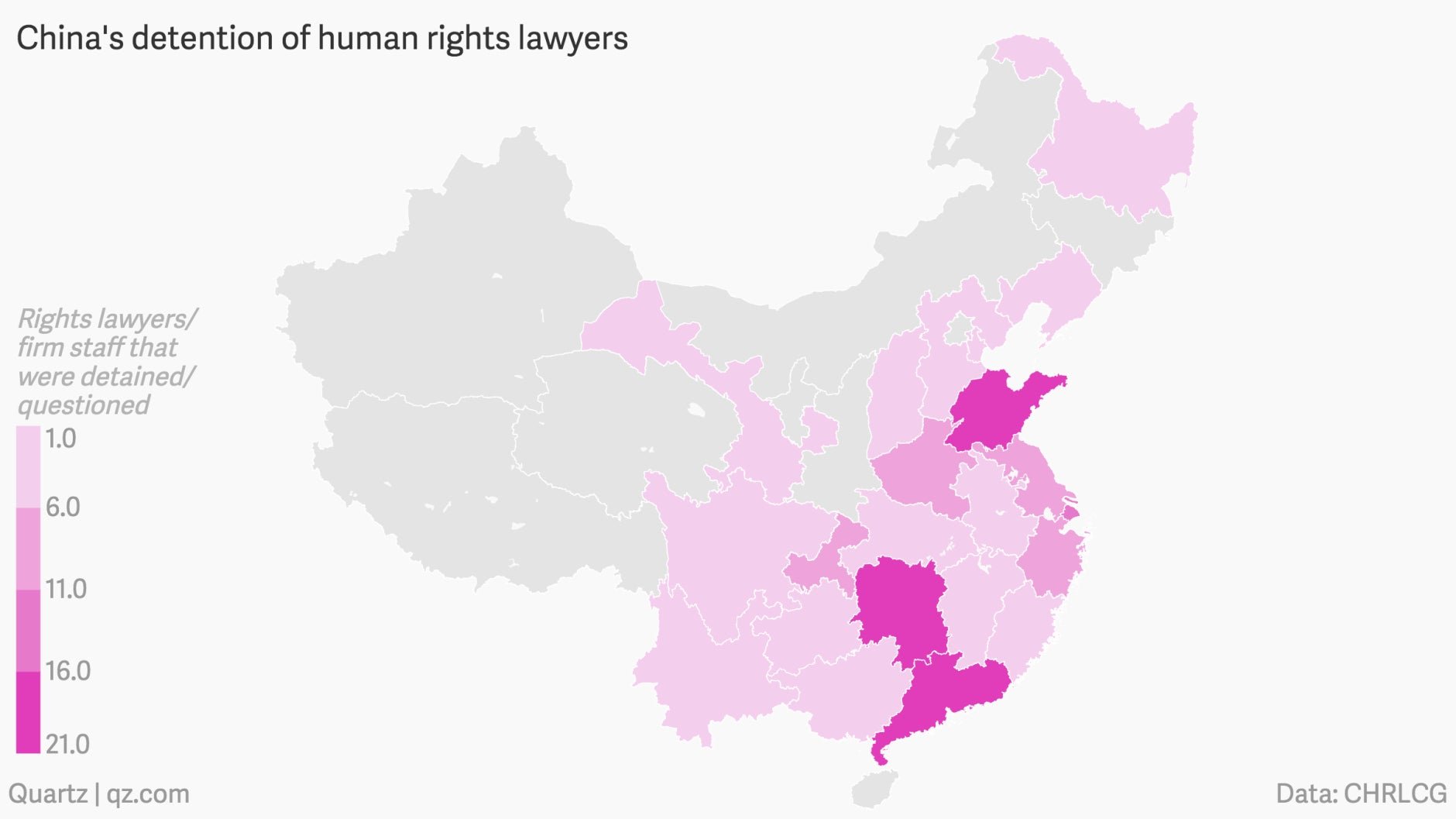

The map below, from the Hong-Kong based China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, shows that 159 lawyers have been detained as of July 2015.

“There’s virtually no accountability for torturers in China,” Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch, tells Quartz. Human Rights Watch issued its own report on the topic in May.

In Amnesty’s report, Hunan lawyer Cai Ying detailed being held for 87 days in 2012, allegedly for suing a member of the country’s judicial system. He told Amnesty that he was questioned for at least 12 hours a day in a hanging chair.

Beijing-based human rights lawyer Yu Wensheng told Amnesty he was detained for 99 days after he supported pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong in 2014. ”My hands were swollen and I felt so much pain that I didn’t want to live,” he said. “I know from personal experience how widespread torture is in China’s current law-enforcement environment.”

But earlier this year, when the UN’s anti-torture committee confronted China with Wensheng’s story within a broader list of issues, China denied that the lawyer had been ”maltreated.” In the same response, government officials described the country’s detention practices as “a management approach”—rather than a violation of international law.