It was bound to happen. When I first got the assignment to write a story on reducing consumer food waste, I was feeling just a little smug. I’m the one who wraps up breadsticks at the restaurant to take home, slurps the last bit of soup from the bowl, cuts the soft spots out of an apple rather than tossing the whole thing away. But even though I personally don’t fritter food, plenty of people do—and this would be my big chance to help reduce the hefty social and environmental costs by exploring why and what we can do about it.

Then I opened my refrigerator. Pulling out what I thought was a perfectly healthy stalk of celery, I found instead the early stages of compost. On the top shelf, a cottage cheese carton disguised leftovers I had diligently squirreled away—and promptly forgotten. And then there was the ketchup. “Best if used by March 2012”? Busted.

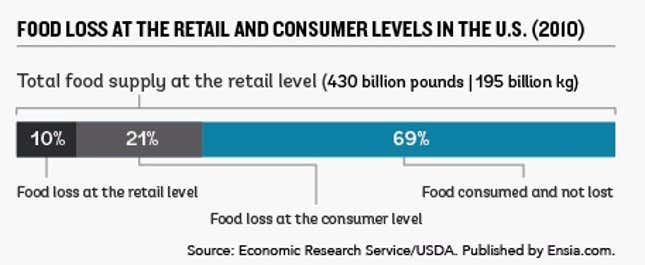

Like it or not, when it comes to food waste, it’s not just industrial farms or supermarkets or restaurants or caterers or other people who are to blame: It’s all of us. In fact, according to The Wall Street Journal, more than twice as much food is wasted at the consumer level than at the retail level in the US.

“There’s good news and bad news,” says Jonathan Bloom, author of American Wasteland: How America Throws Away Nearly Half of Its Food (and What We Can Do About It) and perhaps one of the world’s top accumulators of wasted-food facts. “The bad news is that we are pretty wasteful as individuals and families. The good news is we can be a major part of the change with food waste.”

Capitalizing on that concept, government agencies, environmental organizations, and other nonprofits around the world have been developing and deploying a spectrum of strategies to help consumers reduce the amount of food we waste, from simple awareness-building social media campaigns to gala events in which celebrity chefs demo innovative approaches to turning leftovers, stale bread, forlorn fruits, and the like into culinary creations. In the process, they have learned much about what works—and doesn’t—when it comes to reducing consumer food waste.

Consumer power

Worldwide, one out of every three bites of food produced never makes it to our mouths. Some—especially in developing countries—is lost in harvesting, storage, transportation, and so on. But in developed countries, a good chunk gets tossed out after it’s in the consumer’s hands.

“Consumers, especially in Europe and the United States, we are the main food wasters,” says Selina Juul, founder of the Danish food waste reduction campaign Stop Spild Af Mad (Stop Wasting Food), which got its start seven years ago when Juul, who emigrated to Denmark after living in Moscow during the tight times following the collapse of the USSR, decided she had had enough of the profligate attitude toward food in her new setting.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that in North America and Europe the average individual throws out 95 to 115 kilograms (210 to 250 pounds) of food each year. In the US, that number is more like 290 pounds (130 kilograms), according to US Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service estimates.

Half a super-size jar of jam that was such a good deal but you likely couldn’t consume in a lifetime… the apple and bag of chips prepackaged in the deli lunch… a papaya you purchased but weren’t quite sure how to prepare. It all adds up.

But why is wasting food such a big deal anyway?

For the individual, wasting food is, simply put, wasting money. “One of the things I find so odd is we’re so attuned to the savings on the front end,” Bloom says. “We’ll change what we’re going to buy based on sale items at the supermarket, but we don’t ever think about the cost of food waste on the other side of the equation and how much that adds up to.” On average, according to the US Department of Agriculture, an American family of four throws out close to $1,500 worth of food in a year.

Wasted food is wasted time, too. Juul says a recent survey found people spend four to five hours per month shopping for the food they end up throwing away. “You can save those five hours,” she says. “That’s a lot of time.”

On a societal scale, many argue it’s a matter of justice: Even though distribution and politics complicate the picture, from an ethical point of view there is little to argue for tossing food when others go hungry.

And from an environmental perspective, it boils down to the fact that we are literally throwing our natural resources into the trash. The implications for the planet are huge: According to a 2009 study published in the journal PLOS ONE, fully one-quarter of the water used in the US goes to produce food nobody eats. The Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs estimates that every kilo of food produced embodies 1.3 liters (0.34 gallons) of gasoline. Even after food is thrown away, its environmental footprint continues to grow as the rotting discards generate methane, a super-potent greenhouse gas. In fact, the UK’s Waste & Resources Action Program—WRAP—estimates that fully 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to food waste.

In the know

If wasting food has such negative consequences for ourselves, our fellow humans and our planet, why do we still do it? That’s a question many consumer food waste reduction programs try to answer as a first step in convincing people to do otherwise.

One frequent finding, mirroring my own experience, is that people are simply unaware.

“Most of us think that we don’t waste much food,” Bloom says. “We think, ‘Oh, that’s the other people, it’s the other wasteful folks.’ And it’s really easy to think that way, because we have learned to not see our own food waste. We’re sort of willfully and blissfully ignorant of how much food we are throwing away.” Indeed, in a 2014 Johns Hopkins University survey of food waste awareness, attitudes and behaviors in the US, three-fourths of respondents said they throw away less food than the average American.

To counter this, Bloom recommends composting: Watching the scraps pile up, he says, “forces you to see what you’re not using.” Food diaries are another common approach to helping build awareness of food waste. Food: Too Good to Waste—a food waste reduction program spearheaded by the US Environmental Protection Agency—even offers a downloadable tool consumers can use to measure their food waste on a weekly basis.

It’s not just lack of awareness of how much we waste, however; many of us are oblivious to the personal and societal costs we incur when we waste as well. “We’ve become disconnected from our food and so have lost our understanding of its value—for example, all the resources, energy, and time taken to get it to us,” notes Emma Marsh, head of WRAP’s Love Food Hate Waste, a research-based campaign that has led the way in bringing the consumer food waste reduction message to the United Kingdom since 2007. Despite this disconnect, Marsh notes, “No one intends to waste food or gets pleasure from it. We all want to make the most of our food, but life can get in the way.”

Food waste campaigns have been quick to pick up on the need to educate people about the problem. Virtually all include messaging intended to shock people into awareness of the magnitude of consumer food waste and the personal costs we incur when we throw food away.

“If you want to change the people, if you want to change their mentality, you need to communicate on a level they can understand and also communicate through something that they can relate to and which can be beneficial to them,” Juul says. “And saving money is very beneficial, and saving time as well.”

Make it easy

Just being aware of the problem and its consequences doesn’t solve the problem by itself, though. “You can’t expect raising awareness or providing information to change behavior for the long term,” Marsh says. “We need to offer practical solutions such as cookery classes, budgeting and planning support, better choice of pack size, storage information on pack, etc.”

Often it’s our routines and habits—whether we check what’s already in the cupboard before we shop, what we think is the right number of bananas or buns to buy at one time, how much pasta we think we need to put into the pot—that do us in. According to I Value Food, a food waste reduction program of the nonprofit Sustainable America, one-third of Americans rarely if ever look at what’s in the refrigerator or pantry before heading to the supermarket. And the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations attributes more than half of food waste to poor planning while shopping.

Food: Too Good to Waste works to overcome this by connecting people with an entire array of tools for making it easy to break old routines and start new ones, from a shopping list template to meal planning apps.

Stop Wasting Food published a leftover cookbook (which quickly sold out) and offers an online clearinghouse of ideas for consumers on ways to reduce food waste, from making a meal plan to making pancakes out of leftover mashed potatoes. (A word of warning, though, for non-Danish speakers; the Google Translate version can be a little dicey. Take this helpful hint, for example: “If your carrots are soft and hangs around with his nose, throw them in the water, then into the refrigerator and let them suck, they are just as resilient as before.”)

Meanwhile, on the manufacturer and retailer end, supermarket chain REMA 1000 eliminated volume discounts in Denmark to make it less tempting for consumers to buy more food than they can use. Intermarché, a French outlet, gathered odd-looking produce into a special section and sold it at a discount. Several years ago British grocer Tesco started offering “buy one get one later” rather than the more common “buy one, get one now” deals to help reduce consumer food waste due to over-purchasing.

Consumer waste that occurs in restaurants, cafeterias, banquets and other places outside of the home has been addressed by campaigns that try to instill new habits as well. In Italy, where taking leftovers home is considered poor taste, some restaurants have been working to get patrons to change their perception and encouraging them to save what they don’t finish. In Denmark, Stop Wasting Food has distributed more than 50,000 doggy bags to restaurants free of charge to help the cause. In the US, many colleges have opted to forgo trays in their cafeterias to make it harder for students to take too much food. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, on some campuses this one seemingly small change has reduced food waste by more than one-fourth.

Minimizing misinformation

Misinformation and insufficient information is also a problem. As a result, a number of food-waste-reduction campaigns have focused on quashing misinformation and providing accurate information about how to handle food.

Improving knowledge about how to store food offers one big opportunity for reducing food loss due to spoilage. Food: Too Good to Waste provides a food storage guide, and Love Food Hate Waste has produced a “Best Before Date” series of video spoofs on television matchmaking shows as well as food ditties by comedian-poet Kate Fox to help consumers make good choices about food storage. Knowing when food is really a goner is important as well: Is it OK to use an onion after it sprouts? The unmoldy half of a moldy cucumber? Meat that’s turned brown, or cheese that’s turned green? Packaged food that’s past its “sell by,” “best before” or “use by” date? A 2014 survey of US consumer food waste found that worry about food poisoning was one of the top reasons people throw food away. And in the UK, the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs recommended against using “sell by” and “display until” labels because they erroneously led consumers to think food was no longer safe to eat.

According to Bloom, one of the most challenging misperceptions may be how we view scarcity and abundance. “We want to have plenty of food because for millennia as a species we haven’t been able to just go out to the store and buy plenty,” he explains. “There still is that slight feeling of not necessarily knowing where the next meal is coming from.” To the children and grandchildren of the Great Depression or other tight times, buying and preparing more food than is needed can be a sign of everything from love to having “made it.” Love Food Hate Waste is working to counteract quantity misperceptions with free portion planning tools to help cooks prepare appropriate amounts of food. Other strategies include simply using smaller plates, which can provide the sense of abundance while reducing the temptation to overserve.

Noting that amount of food wasted correlates with demographic factors such as household size, age, and employment status, Love Food Hate Waste reminds us that an important part of any campaign is to figure out the target audiences and their specific interests, needs, and limitations. Food: Too Good To Waste also underscores the importance of engaging consumers with messages and opportunities often, rather than taking a “one and done” approach.

Cool and competitive

As in many things, though, turning the trend has a lot to do with making it cool. Juul, for example, places a high premium on avoiding food shaming and instead focusing on engaging people with edgy, upbeat messaging; a vast social media presence; a lively TEDx talk; and a make-it-cool-to-conserve approach. “What is really important is to deliver a positive message,” she says. “If you have a negative message, like ‘the big, bad supermarkets’ or ‘the big, bad consumers,’ they won’t listen.”

I Value Food offers consumers a way to turn about-to-be-wasted food into a party with instructions for hosting a Salvage Supperclub. In a similar vein, Love Food Hate Waste plays off the “foodie” trend, focusing on food’s value as a source of pleasure and a creative outlet—encouraging people to take a creative approach to preparing ugly or leftover food, for instance. With its Foodwise campaign, Australia-based Do Something! provides recipes from celebrity chefs using leftovers.

Competitions are a popular tool, too. The Hong Kong Environmental Protection Department’s Food Waste Reduction program, for example, encourages members of the public to upload photos of their empty restaurant plates to a special Facebook page for a chance to win a prize. Love Food Hate Waste initiatives include poster contests and school-based races to reduce waste.

Encouraging trends

Clearly there is no shortage of initiatives to educate and inspire consumers to keep food out of the trash. But do they work?

Making cause-and-effect connections between the various strategies these campaigns employ and the amount of food wasted is difficult. But concurrent trends are encouraging.

For example, communities participating in Food Too Good to Waste saw a reduction in preventable food waste of 11% to 48% by weight (27% to 39% by volume). Avoidable household food waste in the UK has dropped 21% since the Love Food Hate Waste program began in 2007. A 2013 survey showed that half of Danes reported reducing their food waste over the previous year, and food waste has declined 25% in Denmark over the past five years.

Juul attributes that success to a variety of campaign strategies by Stop Wasting Food, including getting the attention of media, engaging via social media, avoiding alignment with a particular political ideology and using a variety of messages to avoid tiring people out. But, she says, ultimately it all boils down to one simple thing: convincing consumers that reducing food waste is simple and worthwhile.

“The main message for consumers is, ‘Start doing something on your own because it is so easy,’” she says. “It is so easy to go to the kitchen, see what you already have in your fridge, use your leftovers, and be creative. It will really save you so much time, so much money—it’s a win-win situation, and it’s also good for the environment.”

This post originally appeared at Ensia.