Aung San Suu Kyi’s father is known as the “father of Burmese independence,” because he led what was then known as Burma in its fight against British colonialists who had occupied the country for decades.

Now that Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party has won majority control of the country’s parliament, her supporters—both inside and outside the country—are hoping she will become the mother of an independent democracy in Myanmar. Under her leadership, the country could be the first democracy in many years to peacefully flourish from the ashes of an authoritarian government.

The election victory for the NLD has come at huge personal cost for Suu Kyi, though, and caps seven decades of personal and political upheaval.

Her father’s greatest political triumph happened before she was likely to have had any memory of it. Suu Kyi’s father, a general, garnered Burma’s independence from Britain by uniting the country’s national groups, and signed the independence agreement with British prime minister Clement Attlee in January of 1947.

In July of that year, General Aung San was assassinated by a political rival.

Suu Kyi’s family was still very much in the public eye, though. Just nine months later, she and her brother were photographed eating ice cream with then governor general of India Lord Mountbatten and his wife Edwina:

Suu Kyi studied in New Delhi and Oxford, and worked at the United Nations in New York, then married and moved to London, where she had two children and studied Burmese literature. But she returned to her home country in 1988, where she started a movement aimed at restoring democracy to the country, which was increasingly controlled by the military.

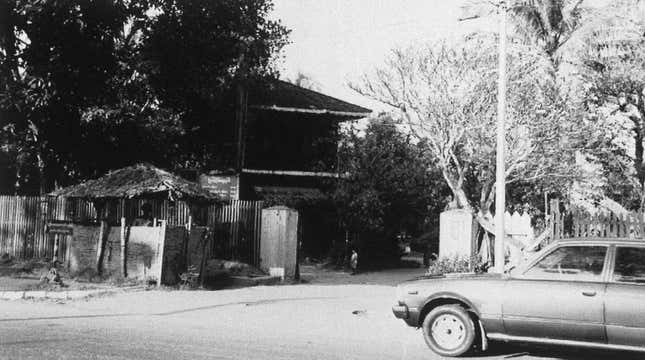

The movement’s popularity made her a target for the country’s autocratic leaders. She was placed under house arrest in 1989, after refusing to leave the country, and remained there for six years.

“We cannot release her, not because she might incite unrest in the country but because we are afraid that some unscrupulous elements might manipulate her and destabilize the situation,” the military junta said at the time. Although the NLD party won a majority in a 1990 election, the military refused to cede control of the country.

Her husband, British historian Michael Aris, and their two children were not allowed by the ruling military junta to remain with her. They returned to Oxford, where Aris was a professor. Suu Kyi didn’t see her youngest son, Kim, for 12 years after that.

Suu Kyi’s husband was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1997, but the Myanmar government would not grant him a visa to visit her. He died in Britain in 1999. It had been three-and-a-half years since the couple last saw each other.

“One wants to be together with one’s family. That’s what families are about. Of course, I have regrets about that. Personal regrets,” Suu Kyi told the BBC in 2012.

She won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, and was released from house arrest in 1995, an event that drew international attention. At a press conference, Suu Kyi said she confident democracy would return to her country.

But her freedom did not last. Suu Kyi was again detained in 2000, then intermittently put on house arrest and released through the next decade. Despite all this, in 2012 she officially re-entered politics, winning a seat in by-elections to fill vacant parliament seats.

With this week’s victory, Suu Kyi will take on a role that she has been working towards for most of her life.