When Christine got out of prison in 2009, she couldn’t find a job no matter how hard she tried. She turned in a dozen or more applications for all types of positions, growing increasingly frustrated as opportunities failed to pan out. The one thing all the applications had in common? A small box asking applicants to disclose whether they had any criminal history.

Christine had served two years in New York state prisons after forgery charges she’d incurred half a decade earlier, in the midst of a drug addiction. After her release, she wanted to get her life back on track. She looked forward to becoming a member of working society. But that application box haunted her.

“My original thought was fuck that, I’m not going to lie,” she tells Quartz. “I’ll be truthful and get a job legit, even with this felony.”

At one point, she got hired at a bar and grill. The manager asked her to fill out an application as an afterthought. Once she turned it in, she never got put on the schedule for a single shift. Frustrated—and desperate to get a job to placate her parole officer—Christine decided to stop checking the box and see what happened.

“The first job I applied for where I lied, I got it,” she said. It was an office job, and everything seemed to be going well. Then, six months after she had been hired, a client told Christine’s manager about her past. Her manager hired a private company to do an audit. When the firm found a $12 discrepancy, she was let go. (Christine says she did not take any money.)

Christine knows she made a mistake lying on her application–and she wouldn’t do it again. But her story is a perfect example of why the movement to “ban the box” is so necessary.

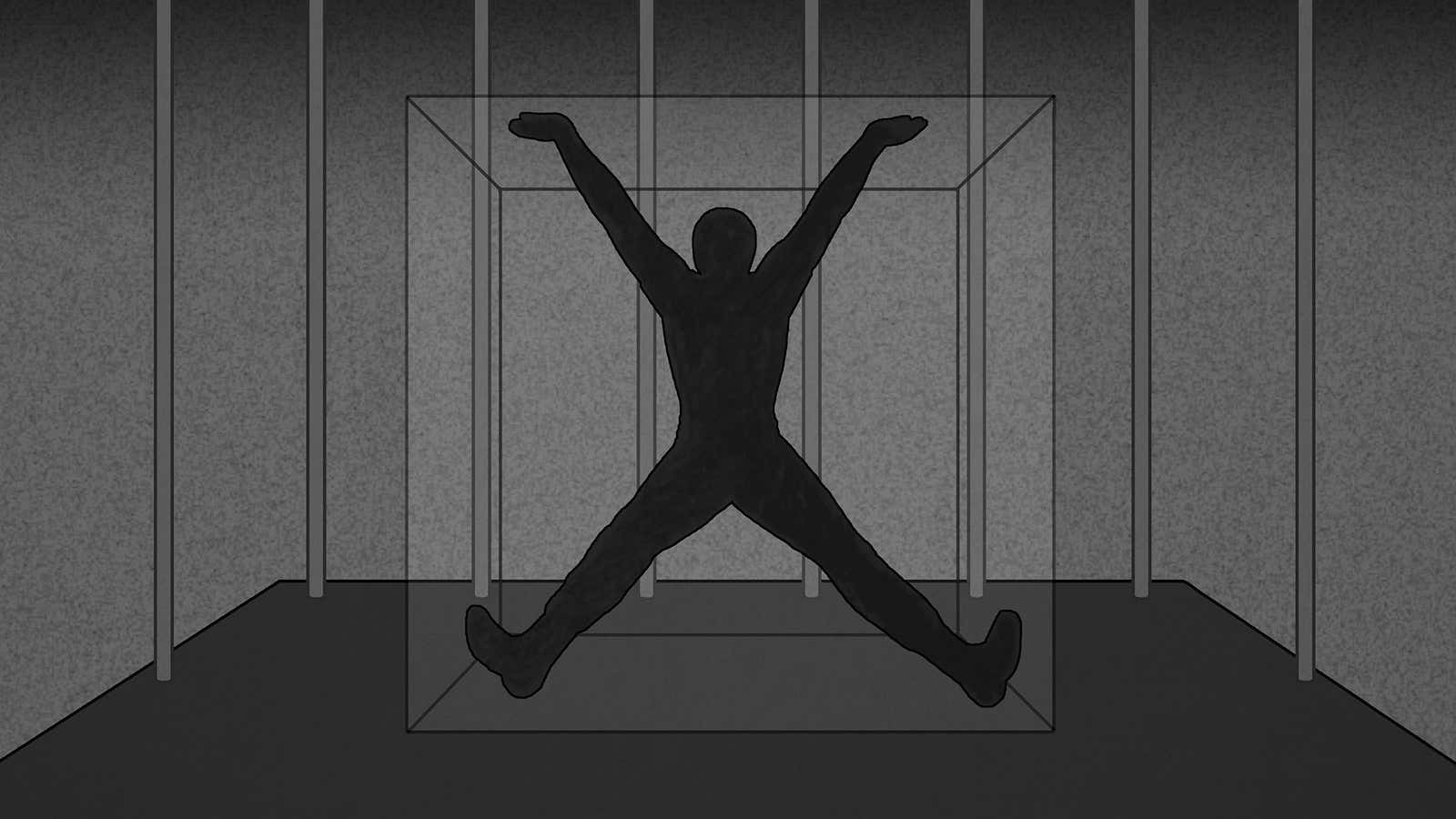

So-called ban the box legislation restricts employers from asking about criminal history on job applications. It demands that they remove “the box” that asks whether a candidate has any criminal history.

Also known as fair-chance hiring practices, ban the box laws don’t forbid employers from asking about criminal records at all. They simply mandate that those types of questions occur later in the hiring process, typically after an in-person interview or a conditional offer of employment. It is designed to help people who want to turn their lives around to get a foot in the door.

So far, the federal government and 19 states—including, as of Oct. 27, New York—have enacted some form of ban the box law.

In a series of 12 executive actions recommended by the Council on Community Re-Entry and Reintegration (CCRE), governor Andrew Cuomo announced a range of changes related to the criminal justice system, including better access to supportive housing after prison, better post-prison treatment options for the mentally ill, and a fair-chance hiring policy.

The steps being taken in New York and across the country are important. But as CCRE member and New York University law professor Tony Thompson cautioned in an interview with Quartz, “These are clearly just a first step.”

Indeed. As it is, New York’s fair-hiring policy doesn’t go far enough to actually help someone like Christine. Christine didn’t apply for any state government jobs—and New York’s Fair Chance Act (FCA) only applies to jobs in that narrow realm. (Some cities within the state, including New York City and Rochester, have passed their own, more inclusive ban the box laws for both public and private employers as a stopgap.)

This is a problem across the country. Only seven states across the country have laws banning the box for all employers in the state. And the federal ban only applies to government jobs.

Of course, fair-hiring practices shouldn’t have to be laws. Employers have the power to hire as they see fit, and some influential ones—like Walmart, Koch Industries, and Target–have jumped on board voluntarily.

“Given [that] one out of three adults in the country have some type of criminal record (felony, misdemeanor, or arrest),” Koch Industries senior vice president Mark Holden tells Quartz in an email, “it would be shortsighted for us to exclude at the outset many individuals who may be talented and want to work hard but made a mistake in their past. None of us want to be judged for the rest of our lives for what happened on our worst day.”

For me, there’s a personal element to this issue. In 2010, I was arrested with $50,000 of heroin in the trunk of my car and eventually sentenced to 2.5 years in prison.

Even still, I’m one of the lucky ones. For one, I work in a profession that is less likely to be influenced by this type of personal history. Most of the writing jobs I’ve applied for wanted a resume and published clips, not an application.

Then there’s the fact that my initial arrest was highly publicized—I lost my right to privacy the moment Gawker published my mug shot and Facebook profile. If potential employers Google me, they’ll know my history right away.

Despite the popularity of shows like Orange Is the New Black, the reality is that for most of us, a criminal conviction is not sexy. I’ve seen my friends struggle. I’ve seen people try to become productive citizens only to find that society won’t let them.

Criminal justice reform activists have been trying to attract attention to this massive problem for years, with little to show for it. Nationwide, there are 70 million Americans with criminal records–a disproportionate percentage of whom are minorities. In a country where minorities represent an estimated 60% of the prison population and one in six black men has done time, employment discrimination has and will continue to have disparate racial effects. That is, unless employers want to start adding a box that says, “Did you commit a crime for which you should have gotten arrested but didn’t because you were white?”

Fundamentally, banning the box isn’t just about correcting injustices or giving people fair chances. It’s also about dollars and cents. Nine out of ten employers do background checks, and the result has been huge losses, often in areas that can least afford it. As Kai Wright wrote in The Nation:

The United States lost between $57 billion and $65 billion in GDP in 2008, according to the Center for Economic Policy and Research, as a result of the reduction in male workers. Of course, that lost productivity is concentrated in black and Latino neighborhoods where it is most desperately needed.

Moreover, if we don’t enable people to pursue gainful employment, we can’t act surprised if they turn back to a life of crime and end up behind bars again. Besides creating a depressing and societally self-defeating cycle, this recidivism is incredibly expensive—and getting more so every day. Maintaining the biggest prison population in the world costs a lot of money, especially when the alternative is giving people the chance to become tax-paying citizens.

Of course, it’s easy to say that a broader ban the box policy would be a good idea. But is it actually realistic?

“I would say yes,” Marsha Weissman, CCRE member and executive director of New York’s Center for Community Alternatives, tells Quartz. “I don’t know if it would happen this year and I think it’s going to be a long struggle, but I think there’s increasing support for that.”

I know I’m not the same person I was five years ago. I’ve served my time and don’t deserve to have what I did at my lowest point held against me forever–and neither does anyone else.